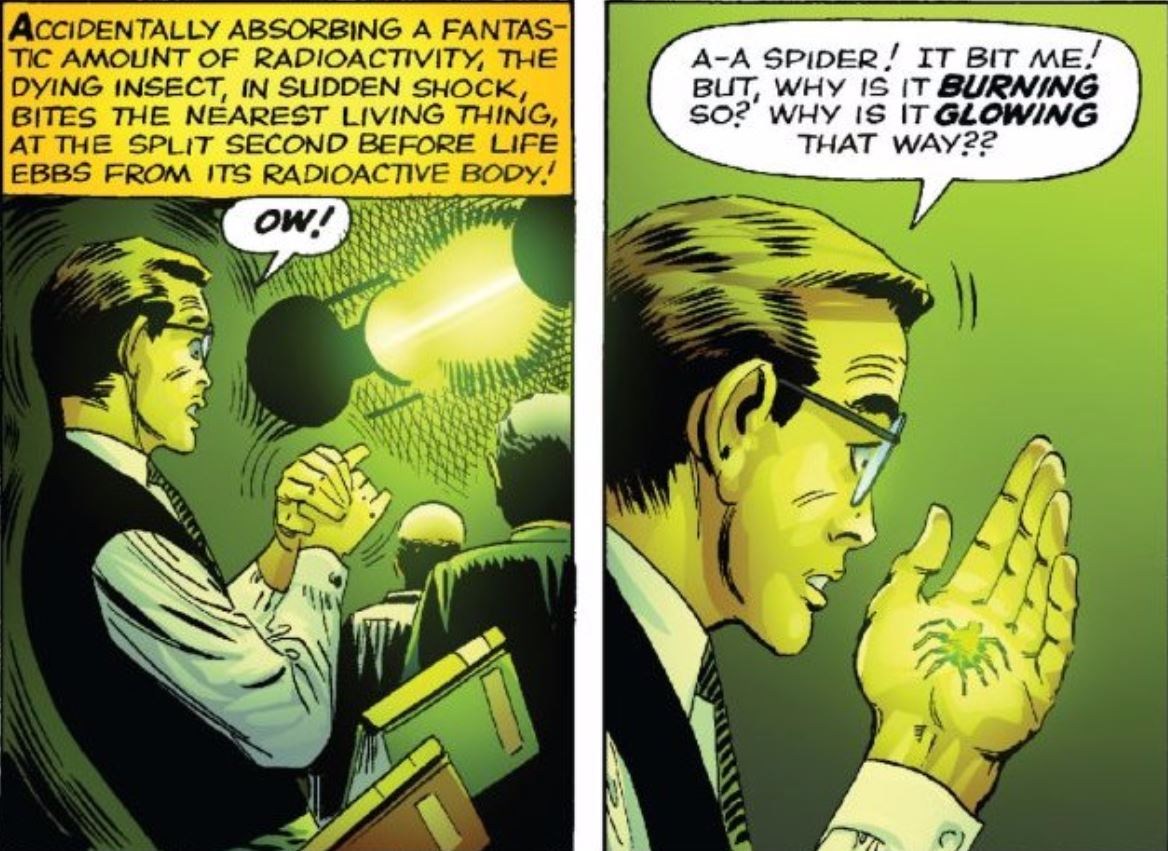

We all know Spider-Man’s origin story – bitten by a radioactive spider, blah, blah, blah.

To call it well-known in an understatement. The spider-bite origin is so familiar, Spider-Man: Homecoming skipped showing it altogether.

That said, let’s hit the high points: Peter Parker was bit by a spider that had moved through radiation or had some form of exotic energy or chemical formula in it. The energy stayed in/on/with the spider and it bit Peter Parker on the hand. In the bite, the radioactive spider passed along some kind of…let’s just call it information at this point. Peter’s body took that information and re-wrote his DNA, blending it with that of the spider, giving him the proportionate powers of a spider.

Blah, blah, blah, spider-powers, Uncle Ben gets shot, Peter becomes Spider-Man. Great power, great responsibility, yadda, yadda. And Aunt May’s is hot now.

Okay – let’s do a little preemptive complaint answering. Yes – Spider-Man’s origin is fiction. No – we know it can’t happen. Yes – Spider-Man is one of the coolest superheroes ever. No – we’re not trying to spoil Spider-Man. What we’re trying to do here is, now that you’re in the door, talk some science.

Because when you think about it – and Peter Parker aside – you really don’t hear about people getting sick from spider bites, and when the news talks about diseases being spread, they’re usually talking about mosquitoes or ticks. In disease terms, we’d say that spiders aren’t vectors, or means by which diseases are spread.

Let’s get into the science of spider bites.

Why Do Spiders Bite?

First off, let’s not paint this all as a pretty picture. Spiders do “bite” and some spider bites are bad for the victim. Black widows and brown recluses are the most famous for bites in the United States with other species showing up in other parts of the world. Spider bites can carry serious health concerns.

Most don’t. The vast majority don’t. And the vast majority of spider bites are not serious.

But they do and will bite humans.

Why?

Not because they’re hungry.

The major biting insects such as mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, mites, lice and bedbugs bite for a simple reason: they’re hungry. For your blood.

Female mosquitoes bite people and other mammals because they feed on blood. That’s it. A mosquito sticks its proboscis into your skins to hunt for a blood vessel, and once it finds one, releases saliva into the wound. The saliva contains an anti-coagulant, which prevents the blood from clotting while she’s feeding. The saliva is also what fires up your body’s immune system which produces histamine to fight the threat of the saliva. The histamine causes blood vessels to swell (that red bump) which can irritate blood vessels (that itch). All that just because a mosquito is hungry. Ticks and fleas are similar in their reason for attack and a resultant histamine response. Your blood makes for good food.

But that’s not the deal with spiders.

Spiders don’t bite humans for any nutritional purposes, so they’re not biting with any part of their digestive system like mosquitoes and ticks are. Spiders bite with fangs.

But typically, spiders only bite humans as a defense mechanism. The spider is on you and feels that it is in imminent danger, so it does the only thing it can – bite you to try and stop you from hurting it or killing it. SyFy movies, and Frodo’s experience notwithstanding, spiders do not hunt humans as prey. It’s like your parents told you – spiders are more afraid of you than you are of them. But – accidents happen. Scared spiders, angry spiders, irradiated spiders, a spider you’re about to roll over on in your bed in the middle of the night – they’ve all been known to bite, but mostly in extreme cases. In fact, unless the spider is caught, red-fanged, most “spider bites” are misidentified bites from any of the above-named bloodsuckers.

What Happens When a Spider Does Bite You?

First off, for a spider to do any damage, its fangs must be strong and sharp enough to penetrate your skin. That rules out a lot of spiders that carry venom. They’re just not strong enough. Veteran spider researcher Chris Buddle has said he’s watched spiders try to bite him, but for most, their fangs just can’t make any headway against his skin.

Of the roughly 40,000 different species of spiders around the world, only about 12 can injure humans with a bite. In North America, the list of harmful spiders drops to just two native species: the widows – black widows and recluses – brown recluses.

So – what happens when a spider does bite its prey or the hand of a teenager who’s on a field trip?

The front end is the biting end. The back end is where the webbing comes from. We’re glad Spider-Man’s not that much of a spider as well.

The business parts of the spider is the called the chelicerae – the familiar pair of jaws in front of the spider’s mouth. Each one has a bulky basal segment which houses a hollow fang which does the deed. The fang is connected via a duct to the venom gland. Once the spider has its prey, the fang swings out and punches in, injecting the venom. Spider venom varies between species, but centers around the common theme of neurotoxin that with either paralyze or kill the prey.

Wrapping the prey up is a common behavior with many spiders post-bite, as is secreting digestive enzymes into the prey, liquefying it and making it easier to consume. That’s what Sam was trying to prevent with Frodo.

So – the worst-case scenario has happened and a spider bit you. Could it infect you with a disease, or you know, ionizing radiation or exotic energy mixed with its own DNA to give you spider powers?

Not really.

Again, let’s go back to the main difference between spider bites and bloodsucker bites. Mosquitoes, bedbugs, fleas and ticks are trying to eat a part of you. Just like you, they start their eating process immediately – they bite with a part of their digestive system, and send some of their saliva into you to help with the blood flow. Along with anticoagulants and other proteins made by the mosquito to prevent the blood from clotting, the saliva can carry parasites, bacteria and viruses that have been riding along in the insect for a while, or that came from the last person the bug bit. Saliva is produced in the salivary glands of the mosquito which can harbor virus, bacteria, and be invaded by parasites. When an infected mosquito bites you, it’s injecting you with a few nanoliters of saliva which can carry thousands of bacteria, viruses or parasites.

What about spiders?

Spider-Man’s origin is one of the most re-told and redrawn in all of comics. That spider better be getting some residuals.

Our eight-legged pals are shooting you up with venom. In most cases, the venom is specific to invertebrates (creatures without backbones), not humans. In spiders with venom that affects vertebrates (and other organisms, such as crustaceans), it most likely evolved for defense and hunting smaller vertebrate and crustacean prey.

As mentioned earlier, spider venom is some nasty stuff, and generally comes in two varieties: neurotoxic (directly affecting the nervous system) and cytotoxic (affecting/killing cells, or necrotic in nature). But – generally speaking, it doesn’t carry bacteria, viruses or parasites. Spider venom is pretty much an equal opportunity killer. Making things rough for cells is what it does. You’d have to be a very tough bacteria, parasite or virus to survive swimming in that toxic soup, just waiting, hoping that the spider will bite something that will offer you a more habitable home. Evolutionarily speaking, you’re making things really, really tough on yourself.

A 2015 study which went back through hundreds of spider-bite reports concluded that the evidence pointing to spiders as disease carriers is extremely thin. More than that, the study concluded that even if a spider has bacteria on its fangs or mouthparts, that doesn’t mean it’s a vector for that bacteria (and resultant disease).

“The medical community should not scapegoat spiders for bacterial infections,” lead author of the study Richard Vetter said. “When examining reports of thousands of spider bites of many species worldwide, we found almost no mention of infection associated with the arachnid-inflicted injury.”

In their study of thousands of spider bite reports, Vetter and his team came to two large conclusions: 1) other insect bites are very frequently misattributed to spiders and, 2) there was only one credible report of a spider bite leading to an infection – from an Australian golden silk spider.

Recent anecdotal reports that spiders can spread Lyme disease are most likely false, since the bacteria that is responsible for the disease depends upon a specific relationship with certain tick species. Investigations into reports of spiders spreading Lyme disease are usually, like explained above, due to misidentification of spider bites, or misidentification of ticks as spiders.

What’s the take away here?

- There are lots of spiders on the planet.

- None of them want to bite you.

- Sometimes, they will bite or attempt to bite people, mostly in extreme circumstances, such as life or death for the spider.

- Of those that bite, only a very small number have chelicerae that are strong enough to push the spider’s fang into human skin.

- Of those that can puncture human skin with their fangs, only a handful have venom that is dangerous to people.

- The venom that does go in is a very small dose, resulting in mild to moderate discomfort. Occasionally, a spider bite will result in a more serious injury requiring medical attention and/or treatment with antivenom.

- If spider venom does make its way into you via a bite, there’s one fully documented case of an infection.

Catch that? With each point, the numbers got smaller and smaller. This is one of those things where someone says, “You’re more likely to get hurt from _____________ than from a spider bite,” and they’re right. On the list of things that you should worry about (sensationalist local news stories notwithstanding) spider bites are very, very, very low.

The irony in all of this?

Something about spiders speaks to our primitive brain. They’re so alien and creepy and foreign and…other. There’s even a specific term explaining our fear of spiders: arachnophobia. We kill spiders because we fear them. Yet – spiders catch and eat disease-carrying mosquitoes, ticks, fleas and other pest insects.

The next time you see a spider hanging out around your house or walking by, let them be. Okay – escort them outside of you must. They’re our pals.

So How Did Peter Parker Get his Powers, Then?

No clue. It’s comic books.

You can look at all the pieces and work through them, but at the end of the day, there’s no way in our world, with our science to explain how a bite from an “energized” spider would give someone some ala carte spider powers. Marvel has moved away from Spider-Man’s original 1962 origin, dosing the spider with a huge amount of radiation to something a little more 21st century – tying the spider to Norman Osborne. Basically, the spider that bit Peter had the “Oz serum” mixed in with its venom. But still…that bite did some amazing stuff.

For instance – something from the spider went into Peter when he was bit. Some bit of genetic material, but not all of it (spiders don’t shoot webbing from their wrists, for example), and was somehow compatible with Peter’s vertebrate, mammalian DNA. That’s a huge jump, genetically speaking. Viruses and bacteria can jump species lines, but somehow turning the genetic material of a spider into an infective agent and then have that agent match with mammalian DNA and insert perfectly adapted versions of spider characteristics into it…that’s not science anymore, that’s magic. The more recent addition of the Oz serum gives Marvel a way to “explain away” any of the science that doesn’t quite match up with our world.

And we’re cool with that. As we say over and over, we’re not here to say the science of superheroes is stupid. It’s a way of talking about some real science. And that’s what we did, right?

Spiders are your friends.