Just look at that image of Batman above.

Owwwww…

It comes from The Batman’s Grave #5 by Warren Ellis and Bryan Hitch. Digitally, you can find it at Comixology here, or your local comic shop will surely be happy to mail it to you during this time when physical comic shops are nearly all closed.

The larger story is Ellis and Hitch’s take on a classic Batman-style story – setting the Caped Crusader up on a virtually unsolvable mystery that taxes him to the limit mentally while also punishing him physically. But the larger story isn’t what we’re talking about today – it’s that shot above.

Owwww…point blank to the shoulder.

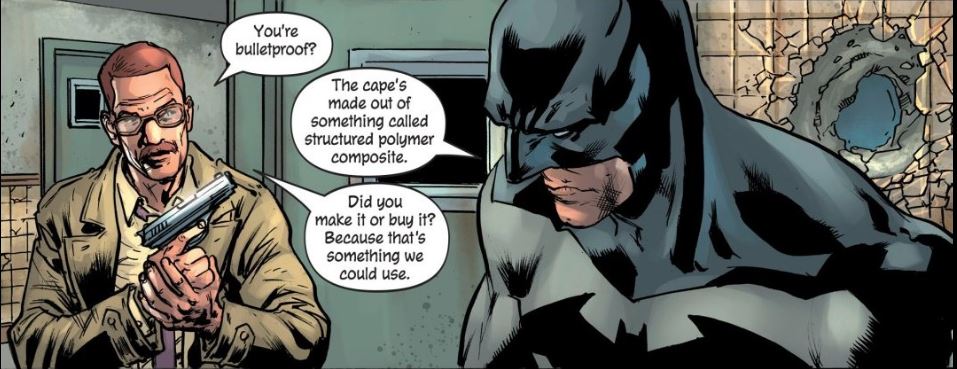

Okay, to be fair, here’s the resolution, a few panels later, as Commissioner Gordon, who witnessed the shot, asks the question we all are wondering:

Great moments in Batman/Jim Gordon history. (c) DC Comics

Batman’s answer – he references something called a structured polymer composite, which, to be fair, does sound like pure comic book stuff, right up there with unstable molecules. Answering Gordon’s question about where it came from, Batman gives a semi-smartass answer:

Bat-snark. We all know WayneTech made it, buddy. (c) DC Comics

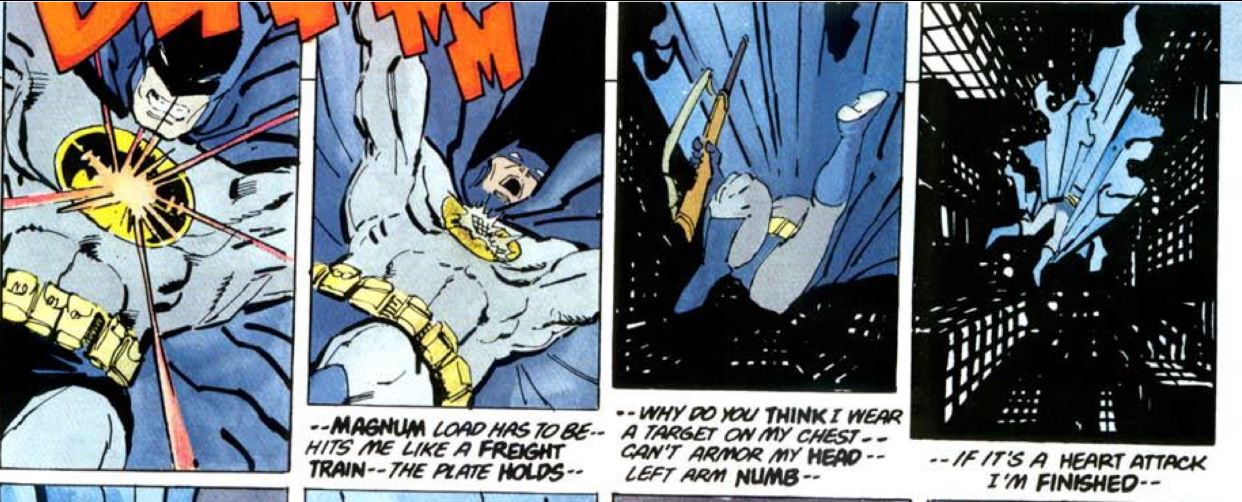

Okay – now Batman has used any number of bulletproof materials in his costume over the years, perhaps none more famous than his revelation that in The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller, he wears armor plate under his iconic chest symbol.

Batman thinks a lot – a LOT – after getting shot in the chest (c) DC Comics

In the narration, Batman suggests that he wears the iconic sigil with its armor underneath to draw gunfire specifically towards his chest, since – as he says, “can’t armor my head.” Well, okay, body armor developments since The Dark Knight Returns came out to the side, yeah, given a choice, you wouldn’t want to suggest that someone with a gun should shoot you in the head. That’s a valuable protip, right there.

But back to the structured polymer composite. As a writer, Warren Ellis does his research, and here it’s no different. Structured polymer composite is real stuff, and has been around for a while.

And it’s kind of amazing.

Composite materials are just materials that are made of two or more components that have different properties. Combine the pieces, and you get something new with its own set of distinctive properties. Composites aren’t mixtures – there’s no blending of the parts, and no solute/solvent relationships – the parts of a composite remain distinct from one another in the final stuff. Concrete is a composite material. So’s plywood, papier mache, and fiberglass. Wood is, by itself, a composite of cellulose fibers held in a matrix of lignin and hemicellulose.

We’ve known about, and have used composite materials for a long time. Composites can be made in a variety of ways, from just mixing materials, such as with concrete, or sandwiching them together, layer upon layer.

It’s this sandwiching that is used to create structured polymer composite. The composite is made of alternating rubber layers for flexibility and glass layers for strength – at the nanoscale level. They’ve been used for years – and in body armor, too…come on Gordon.

But one of the relatively recent breakthroughs in the study of these specific composites came as the result of a collaboration between MIT (remember where Batman said he found it?) and Rice University, as researchers investigated how the material dissipated the forces of impact from projectiles. Using a different polymer with actual 9-millimeter bullets, the researchers showed that not only did the material stop the bullets, it closed up behind them, resulting in bullets embedded in a block. Cool, right? But they wanted to know why it worked like it did.

By testing the ideas on a much smaller scale using micrometer-sized glass beads fired into thin layers of material that could be analyzed under an electron microscope, the researchers saw what they believe happened on the larger scale. From the images, it appears as if the material absorbs some of the energy from the projectile, converts it into heat, and melts. As the projectile continues into the material, it also deforms the material, resulting in the “bent” look for the previously horizontal layers. Taken together, this is a clear indication that the material absorbs a significant portion of the projectile’s energy without shattering or fragmenting.

Dr. Ned Thomas explains below…

The fact that Batman was using this material as part of his body armor was no stretch – the research was funded in part by the U.S. Army Research Office and as Dr. Thomas mentions above, one of the applications for the material is for better body armor (as well as turbine and satellite protection).

Making it flexible enough for a cape, admittedly one with tactical abilities, though? Doable. Flexible structured polymer composites can be fabricated, although there will be tradeoffs between the function with the added flexibility, compared to rigid composites. Hey – and this is Bruce Wayne we’re talking about here. While he humble-snark suggested he stole it from a dumpster, the idea that WayneTech would be working on materials such as this has rock-solid logical consistency within the DC Universe.

Transitioning the material form our world into Batman’s world would need some help, too. As can be seen, using it as a cape presents a different type of problem, separate from the material’s ability to absorb and redirect the force. If the cape is a few inches away from Batman’s body, or even if it’s right up against it, a lot of the bullet’s force will still go through the material and ultimately push on Batman. Worse yet, at the close range shown here, the force would be localized into a very small area, meaning the pressure Batman would feel in that spot would be very, very high. It’s why vest-wearing police offices still grunt or howl in pain when they get up after their vest stops a bullet. It hurts. Oh, and the vest has to be trashed – it no longer has the structural integrity to stop a bullet.

But what about a cape? That pressure, slamming into Batman – would it be enough to break his scapula? Maybe. And Batman’s answer when asked if it hurt?

“Like hell.”

Probably an understatement.

For more:

The original research paper from 2012: High strain rate deformation of layered nanocomposites in Nature Communications