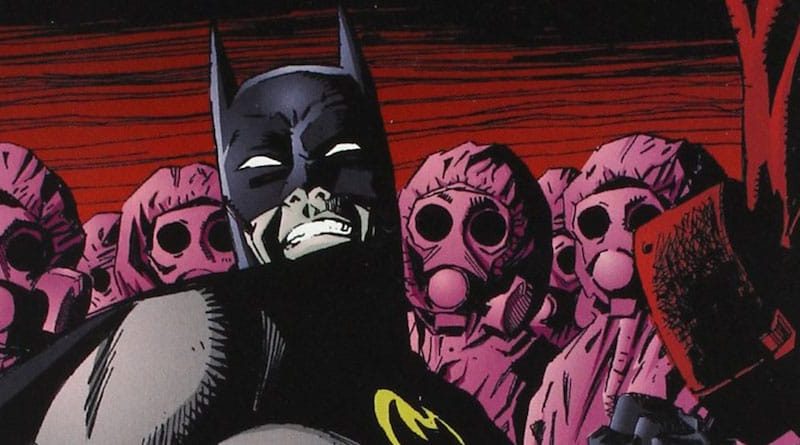

People falling ill from a new, mysterious virus. Hospitals overwhelmed by the sick and dying. An unprepared, overly-politicized leadership forced into reaction rather than proactive steps. Refrigerator trucks called in to act as temporary holding for overloaded morgues. Civilians having to step up to save the day. And Batman.

While you can catch versions of everything mentioned above just by watching the news, all of this also happened in Gotham City 24 years ago this spring. Back then, it was called Batman: Contagion, an 11-part story spanning all of DC Comics’ Batman titles. You can get a digital version at Comixology.com, or give a call to your local comic shop and ask them to mail you out a copy. Seriously – go for that latter one. The comics industry is in a tough spot.

Contagion was very much a product of its time. Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone had come out in 1994 (after starting its life as an article in The New Yorker, “Crisis in the Hot Zone”) which introduced the country (and much of the world) to the idea of viruses that cause hemorrhagic fever. The film Outbreak with its own flavor of hemorrhagic fever, “Motaba” hit theaters in 1995 and the miniseries based on Stephen King’s The Stand aired in ‘94 as well. The Cold War was freshly over, and the collective consciousness was looking for a new doomsday to snuggle up with.

An outbreak of a deadly disease was part of the zeitgeist, so why not Batman?

Looking at this time for Batman specifically, this was the decade-plus of the big, bloated Bat-stories. The story of the breaking of Batman by Bane and his eventual retaking of the cowl – Knightfall – ran from 1993-1995, and after that, there were very few “quiet times” for the Batman books through the decade. Knightfall led to Contagion, which led to Batman: Legacy, and then Batman: Cataclysm, and then, Batman: No Man’s Land which finally ended in 1999. No Man’s Land spanned 80 – not a typo – 80 parts.

Re-reading the Contagion arc in the present day is…interesting to say the least. As some commentators have pointed out, watching pandemic-based entertainment such as the 2011 movie Contagion or Outbreak during a real pandemic puts the viewer in a weird spot of knowing as much as and identifying with the fictional doctors and CDC researchers, rather than the traditional point of view characters. Batman’s Contagion storyline is no different – it still entertains, some of it – such as the refrigerated truck coming into the city to help with the overflow of dead bodies feels prescient, and some, like some terminology and the speed with which a cure is found, is still solidly fictional.

But let’s dig into the story and use it as a chance to talk about the spread of a virus through a population, and this whole R0 or “R-naught” thing is that we’re trying to attack is anyway.

A Bad Time in Gotham…

Spoilers ahead for a 24-year-old storyline, so if you’re wanting to read it all, you may want to bail now and come back after. The collections have a few extra issues jammed in aside from Contagion’s original 11, and some elements of the storyline are skippable (Batman’s encounter with Garth Ennis’ Hitman), some will kind of freak you out (Catwoman openly flirting with a teenage Tim Drake Robin), and some will make you wonder if the different writers knew what the others were writing, or what the overall storyline was, but hey, it’s a period piece of comics. It’s part art and part document of the pop culture landscape of the time.

Okay – Daniel Marris is unknowingly infected with Ebola Gulf-A, which was being tested as a bioweapon of the Order of St. Dumas, a weird religio-mystical order that spawned Azrael, of whom, the less said, the better. Marris is a St. Dumas believer, and knows about the virus, but has no idea he was infected until it’s too late. The virus, Ebola Gulf-A is a fictional type of filovirus which results in a hemorrhagic fever as well as the muscles spasming so hard they break bones. It’s aptly nicknamed “The Clench.”

Marris returns to Gotham City – to the well-to-do Babylon Towers where he informs the other residents of a coming plague and suggests they lock down the self-sufficient condo complex and kick out all of the help – which gives that part of the storyline a serious Masque of the Red Death vibe. The now-infected help go out into the city, the Marris-infected residents of Babylon Towers lock themselves up, and we’ve got a ball game.

Batman is tipped off about the virus coming in from Azrael and learns that the military knows of the virus and has restricted its research. But he’s Batman. Along the way, we learn that there had previously been an outbreak in Cape Heyjadik (yeah – not a real place with a name like that…) with three survivors. Robin is sent off to find them, and Catwoman and Azrael show up with him as well.

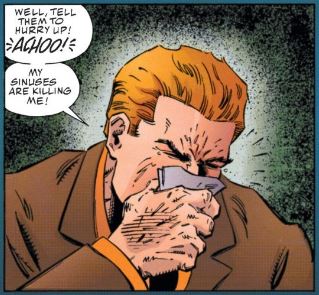

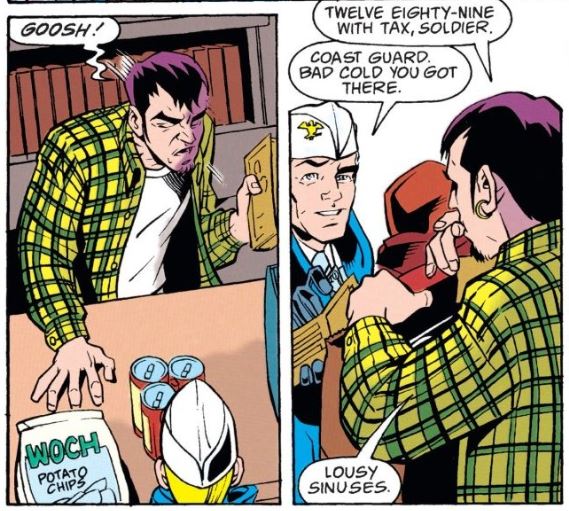

Meanwhile, Marris – Gotham’s Patient Zero dies, and the Clench is ripping through Gotham City – early symptoms are a nasal congestion thing, which apparently causes a lot of sneezing on other people (Gotham City residents don’t care about manners), like this…

It starts like this… (c) DC Comics

THAT IS A NON-ELBOW SNEEZE VIOLATION, SIR! (c) DC Comics

Closer, but no coverage. (c) DC Comics

Oh, come on! (c) DC Comics

Goosh? Goosh is a sneeze? (c) DC Comics

Criminals are a cowardly, superstitious and surprisingly spitty lot (c) DC Comics

Hospitals are quickly overwhelmed, we learn that the “gestation” period (infection until death) is a maximum of 48 hours, antibodies from survivors break down shortly after the survivor dies, the fatality rate is somewhere above 90%, the media goes right to calling the outbreak “plague,” refrigerator trucks are called in to handle the body overflow, the survivors were somehow immune, so they never had antibodies, and oh yeah – Batman has a giant-ass, really weird…microscope?

What the hell? (c) DC Comics

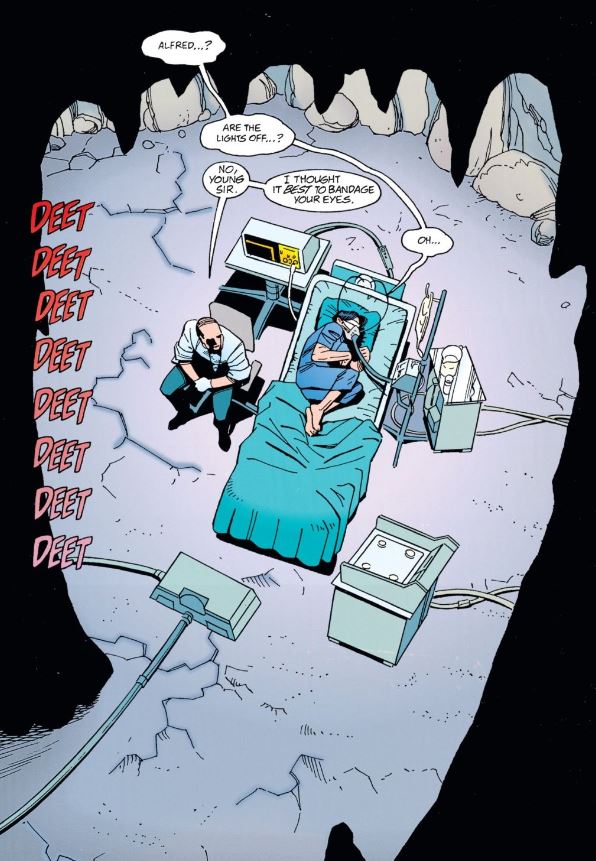

Oh, and Robin gets infected, and you have this panel, which, despite the over-the-top nature of the storyline still lands like a punch in the guts.

You have no heart if this doesn’t make you feel something. Also – unsanitary conditions. (c) DC Comics

The main outbreak and dying lasts for maybe…a little over three days? It’s hard to tell – day/night cycles in Gotham City are just…wonky and the sky color is sometimes green, sometimes purple…and Batman never seems to sleep throughout it all. A lot of people die, but in the end, friends of Azrael find the cure in old books that they had stolen from the Order of St. Dumas, a cure is made, it’s 100% effective, and everyone who was sick (including Robin) gets better.

Yeah.

Again, the entire thing is an amazing, garish, over-the-top car wreck that you just can’t look away from. Re-read today, with what we know now…again, there are a few points that were hit dead-on, but a lot is just pure fiction.

Let’s talk about the spread of the Clench through a present-day lens.

R-naught: The Clench vs. COVID-19

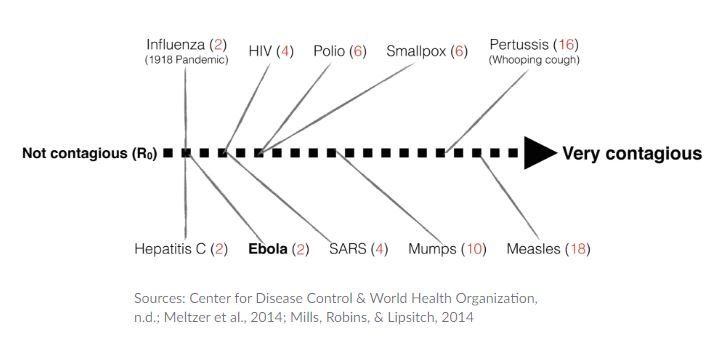

As mentioned earlier, thanks to living through this, it’s like we’re all suited to be pandemic consultants for 25-year-old entertainment. Case in point, pretty much all of us have heard the term R0 or “R-naught.” In case it’s fuzzy, R0 is the reproduction number of an infectious disease outbreak, and there are two versions: basic and effective. The simplest, important thing to remember – high is bad, low is good, and both are dependent upon the situation. They’re not locked-in, constant, hard and fast numbers, and are often expressed as a range. Also, R0 doesn’t give an estimate of how fast an infection is spreading through a population – that’s infection rate. We’re going to cover that later.

The R0 of a disease is how many people an infected person will infect if the original, infectious person were to enter a homogeneous community that was completely susceptible to the disease. Like most models in science, it’s based on an ideal situation, in this case, no immunity to the disease – which is why it’s R-zero. There is zero immunity – the population has never seen the disease before and no one is vaccinated – just like with The Clench or COVID-19.

This has nothing to do with what you’re reading right now. It’s just funny. (c) DC Comics

What was just described above was the basic reproduction number. That’s what happens if nature just has its way – it’s the maximum potential of a given disease. Any disease’s R0 depends upon a variety of factors, including the transmissibility of the disease, how often infected people come into contact with susceptible people and the length of the time the person is infectious. While there are many methods to calculate the R0 of a disease, but the simplest approach is with some pretty easy math:

R0 = new cases of the disease/existing cases of the disease

For example, if there are two initial cases, and at some point in the future, there are new four cases, then,

R0 = 4/2 = 2

That’s a super-clean example that’s not always seen in the real world, which is why actual R0 numbers are given as ranges of numbers with decimals. No, no one is suggesting that half a person can catch a disease. That’s weird.

This is one of those things that are perhaps a little easier to conceptualize if we get some numbers and real examples into the discussion. The seasonal flu – the one that we do (should) get vaccinated against every year? That has an R0 that ranges between 0.9 and 2.1. That means that on average, a person infected by the flu will infect between 1 and 2 more.

Some other R0 values of interest:

| Disease | R0 |

| polio | 5-7 |

| smallpox | 5-7 |

| SARS | <1 – 2.75 |

| measles | 12-18 |

| COVID-19 | 1.4 – 4.46(*) |

| chickenpox | 10-12 |

| Ebola (2014) | 1.51 – 2.53 |

Yeah – those are some wide ranges, and of note for us (*) – COVID-19 is still all over the place, because the data is not 100% clear, and changing. Also – remember the greater world at the time of Batman: Contagion – we were terrified of an Ebola-like outbreak. But really, Ebola tends to show a relatively low R0 for a variety of reasons.

If the R0 of a disease falls below 1 then the disease will die out in a population – the infected person is infecting “less than one” person, on average. That’s good. Look back up there at measles with its R0 of between 12 to 18 people. One person infected with measles can infect between 12 and 18 other people – who will then go on to infect between 12 and 18 other people, and on and on…we’ll look at the math later this week, but part of why measles has such a high R0 is that, as a disease, it’s highly infectious. The higher a disease’s R0 is, the harder it is to bring under control, which is why a measles outbreak can burn through a community with rather terrifying speed. #RememberDisneyland2014

You can also have situations where the effective R0 spikes as the result of one person – a “super-spreader,” who unknowingly infects dozens or hundreds of people. In the case of COVID-19, there are reports of individuals at parties, church, or other large social gatherings infecting many other people. Obviously, this is also what we’re trying to prevent from happening during this pandemic.

The R0 trends to the higher value if the population is large and more susceptible – weakened immune systems, poor nutrition, no immunity, the infectiousness of the disease/organism, etc. If the population has immunity spread throughout and is in relatively good health, the R0 will trend towards the lower value.

As a population in the midst of a pandemic caused by a disease with an estimated “mid-range” R0 value, we like the idea of the lower value. And as mentioned earlier, the population itself can bring down the effective R0 of a disease by doing things that we can all recite by heart now – practicing good hygiene, social distancing, isolating the vulnerable and those showing symptoms and those who have had exposure to infected individuals. Anything that can be done to prevent one person from infecting another person lowers the effective R0. We’re trying to bring it down to a value lower than 1.

Again, if you’ve got an R0 of less than one, the disease will die out within that population.

If you’ve got an R0 of 1, the disease will remain stable within a population. It’s not spreading, it’s not dying out.

If you’ve got an R0 greater than 1, the disease will spread exponentially.

By the way, we’re in that last of the three options. We want to be in the first category. To get there, we’re going to have to go through a period of R0 = 1-ish.

Back to Gotham and Ebola Gulf-A

So what’s an estimate of R0 for Ebola Gulf A, which causes The Clench?

In our world, Ebola has an R0 that hovers around 2. Back in 2014, we all had a momentary flash of panic as it was revealed that the outbreak in Africa had resulted in an infected person coming to the US, in Dallas. And this strain of Ebola was bad – it killed an estimated 70% of the people who became infected. Visions of Outbreak were going through people’s heads.

But it didn’t happen – its R0 stayed low.

Why? Transmission. While a type of filovirus, Reston does travel through the air, Ebola tends to spread through body fluid – blood, vomit, feces, etc. Materials that contain the virus. And people with Ebola generally aren’t contagious until they show symptoms. And then, the virus’ most effective mode of transportation is via fluids that, bluntly, usually stay inside the body. Isolate individuals suspected of infection, and you can squash an outbreak right away as R0 falls to zero.

Clearly, this did not happen in Batman’s town. Ebola Gulf A was being spread through droplets as a bunch of the population sneezed, spat and coughed on each other. Seriously Gotham? Not only was the viral transmission highway outside the body (which is really bad), you folks have no sense of personal space, and…just…gross. As far as we know, “our,” human-infecting” Ebola doesn’t play that way – there’s scant evidence that shows it to be spread airborne or by droplets. But Ebola Gulf A clearly does play that way.

The Clench does its thing. (c) DC Comics

That alone will bump up the R0 value.

Also – along with being extremely transmissible, Ebola Gulf A was highly, highly infectious. If someone horked a loogie on you, you needed to start making funeral arrangements – oh, and you, too were also highly infectious.

Again, that’s going to bump up the R0.

Ebola Gulf A is novel to Gotham. In theory, no one has immunity. The population is highly susceptible.

That’s going to bump up the R0.

Gotham is crowded, and no one is getting away from each other. Due to the rapidity of the onset, there’s no call for social distancing, or quarantines of the possibly infected.

That’s going to bump up the R0.

All the while, nothing was being done to reduce the effective R0.

As for a number for this nightmare scenario that was clearly accelerated for the sake of drama…honestly, who knows? Ebola Gulf A’s fictional characteristics blur the lines, but it spread fast through the city. Fast enough to unsettle Batman. A measles-like R0 of 18? Maybe? More? Less? It was fictional, and frankly, given the world we live in now, trying to estimate an R0 value for a fictional pandemic feels like we’re stretching this whistling past the graveyard a little thin.

But wait – good news?

Gotham Got a Quickie Out. We’re in for the Long Haul.

Spoilers again – the ending to Contagion feels…unsatisfying. It’s very much deus ex…er, liber – at the 11th hour, a cure is pulled out of a book that Azrael’s pals just happened to have stolen off-panel, the cure can literally be made by simple, simple stuff, and it just happens to have 100% effectiveness, and everyone has a pretty happy ending (minus the thousand or so who died over the course of the storyline). Literally, that ending happens over the course of about one and a half pages.

I really don’t like this guy. (c) DC Comics

Yeah – we’re not going to get the Batman ending with COVID-19. We get to keep hammering away at the R0 of this thing.

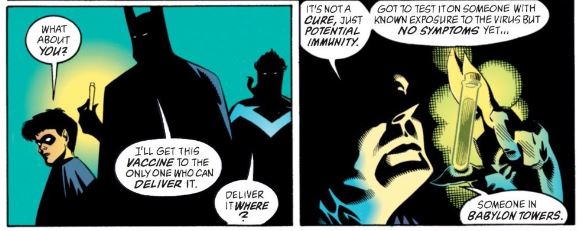

There are many things being done to help, and at last count, 90 or more different vaccines are being worked on. R0 helps us with vaccination as well.

From the R0 value, we can calculate how much of the population needs some form of immunization – vaccines are the most efficient form of that – if we’re going to achieve that sought-after “herd immunity,” where the disease can no longer gain a foothold within a population, and the group is protected against future outbreaks.

Just to do that, we want to get the R0 of the disease down to 1 (taking it down to zero is what you’re doing when you eradicate a disease). That value of 1 means that the disease would no longer be spreading and would be manageable.

To figure out what proportion of a population has to be vaccinated, you can just set up a formula:

1 – (goal R0 )/(actual R0 )

The goal R0 would again be 1, and whatever your disease R0 value is goes in the denominator. That piece there – (goal R0 )/(actual R0 ) – represents the fraction of your population that would still get sick. Subtracting that proportion from 1 will tell you how much your population needs to be vaccinated.

Let’s use smallpox’s lower value of 5 for an example. If we want to protect a population from getting smallpox (we wanted to, and we did, and smallpox is now effectively eradicated), we’d set things up like so:

1 – 1/5 = 0.8

To achieve full herd immunity, which would bring the effective R0 of smallpox down to 1, we would have to vaccinate 80% of the population.

Just playing with numbers, it’s easy to see that the percent of the population needing to be vaccinated increases with larger R0 values, and decreases with smaller R0 values. The higher the R0, the higher your vaccine coverage needs to be. Measles, with its large R0 of 18 requires 94% of the population needing to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity. We haven’t gotten there yet.

For reference, Batman’s experimental vaccine glowed. Ours won’t be so cool. (c) DC Comics

And as an aside – vaccination isn’t the only way to achieve this herd immunity – quarantining, isolating to stay safe from infection, will also prevent new cases from spreading. Vaccines just happen to be effective and efficient at doing the job. And you don’t have the problem of many people dying while you let the disease run free in a population while you’re waiting for herd immunity to kick in, which the U.K. was flirting with for a little while.

So let’s do the math for COVID-19 – just in case, maybe Azrael appears with one for us tomorrow. Let’s call COVID-19’s R0 for this exercise at 2.65-ish. That number represents a middle ground of the range that’s been around. Let’s run that through:

1- 1/2.65 = 0.62

62% of the population would have to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity and be safe. Of course, that’s not considering the time to find and gather the materials needed for the vaccine, the time to manufacture and the distribution of a little over 203 million doses of the vaccine. And that’s the optimistic hurdles we’d need to cross.

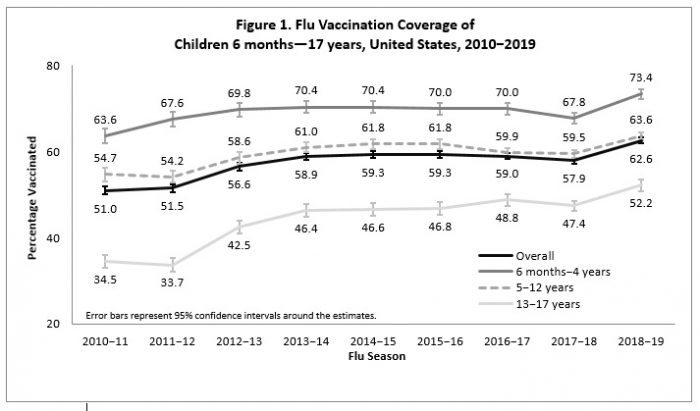

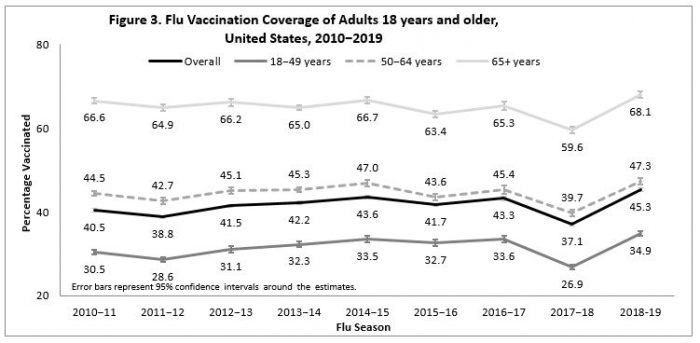

Thing is, as a country, the United States isn’t hitting near that number. We’ve been getting better, and the total number of vaccinated individuals has been steadily rising, and the 17 and under crowd is seeing around a 62% vaccination rate, but the 18 and older crowd? That hovers at an average of around 45% vaccinated, with senior citizens up at around 68% and 18-49-year-olds at about 35% vaccinated.

We’ve got a long way to go.

And this wasn’t even the bad news. Wait until we talk about exponential growth. That’s coming up. Won’t be as long as this. Promise.