We make no secret about it here at thesciecenof.org, we’re both (me, Matt and wife Shari) in STEM Education – high school science teachers. Currently, we’re both teaching our classes online with varying degrees of success, but nothing nearing the levels of engagement and understanding of new material that we see in face-to-face instruction. We have to go back to our schools – for so, so many reasons. Too many to get into here.

But how will we go back? That’s the question that districts and school administrators have been wrestling with since the scope of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak was understood. It will require isolation and social distancing for a while, but sometime – life will have to get back to some new normal, where COVID-19 is part of the landscape for the foreseeable future. Ther have been dozens of stories written about how schools will, should, and might reopen. There are think tanks with education policy experts, industry leaders, politicians, heads of school districts, maybe a savvy political donor or two, but rarely – so rare so as one could safely say almost never, to you see a current boots-on-the-ground teacher among the group. It’s not a big deal – as teachers, we’re used to it, actually – those who make the rules about what goes on in the classroom aren’t in, rarely come from, and never visit classrooms. We roll eyes and roll on.

But this is different. This is, in some cases, literally life and death. Hey – I’m a teacher and hey, I have a website. Hey – I’m going to explain some things from the point of view of a boots-on-the-ground classroom teacher.

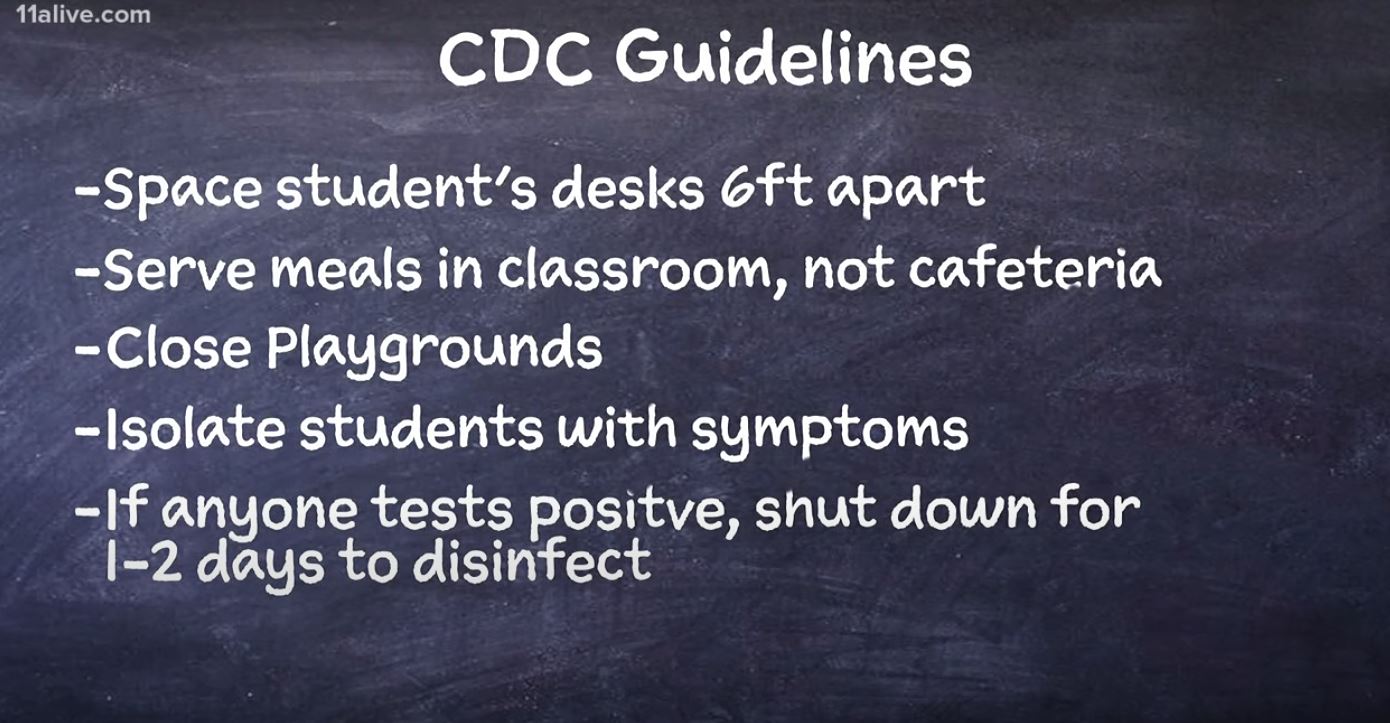

So let’s talk guidelines for reopening. In what’s become somewhat typical for the management of the virus response, there’s been news and controversy surrounding a report from the CDC that offered guidance for schools in regards to opening and operating in a COVID-19 world. Some elements of the report made it to the media and were reported, and perhaps better known, the report was reportedly shelved by the administration for being overly prescriptive but then leaked to the media anyway.

I’ll unpack some of the other guidelines later, but let’s just take a quick look at some as they were reported by 11Alive in Atlanta.

So these new guidelines?

Yeah.

That’s a lot to unpack right there. That’s why we’re only going to start with the first one – spacing students six feet apart. Just to further clarify – this is not 11Alive’s “read” on the guidelines, the CDC guidelines recommend that seating should be spaced to “at least six feet apart” during Phases 1 and 2 of reopening, and continued, if possible, during Phase 3 of reopening. Click here for the full leaked CDC document via Ars Technica, page 5.

Now – before going on, I’m of two minds about these guidelines. One is that someone in the CDC, acting in a totally subversive way, made these recommendations in fact to draw the scoffs and in some cases, guffaws from teachers and school officials in order to both protect students, but also to draw attention to the plight of the schools – suggesting a plan that a majority of schools can in no way comply with, thereby sparking off a national conversation about schools and education which leads to positive growth for both. My other thought about these guidelines is that they are well-intentioned, but like so, so many guidelines that come to schools and teachers, are decided upon by individuals that are completely unfamiliar with how a school or public education in general works.

Having been in public education for more than a decade, I hope for the former but bet on the latter.

Oh, and in all of this, I’m going to be focusing on the CDC guidelines. I know there are other guidelines out there that get quotes and cited, but something like the American Enterprise Institute’s “blueprint for reopening” is aimed more at the business side of things (urging older teacher to retire to save districts a few bucks here and there, reject collective bargaining from unions, look for places where austerity cuts can be made – never let any good crisis go to waste, I guess…), where the CDC’s guidelines are squarely aimed at protecting the health of the students, teachers, and other people who work in the schools. Your mileage and values may vary on which guidance you chose to follow, obviously.

Oh, and I’m going to totally dodge the idea of when schools will reopen. That all depends on things like things you can’t ignore – like a second-wave outbreak that will most likely be coming along sometimes this fall or later summer, and other things that you can ignore, such as any guidance from the administration about Phases and reopening. Most states that are reopening businesses right now (my own included) are saying they’re in Phase 1, which is largely modeled off of the administration’s guidance and Phases. The thing is, while states are reopening in their own Phase 1s and being cheered on by the administration, no state has even met the criteria the administration set for being in Phase 1.

Adding to that, the President is suggesting that schools should open, but opening schools isn’t part of the administration’s Phase 1 – it’s in Phase 2 in a limited fashion. Again, no state that is opening is close to the administration’s Phase 1 guidelines, so yeah – no state that’s reopening in its own “Phase 1” interpretation – that don’t include opening schools – is anywhere near the administration’s Phase 2.

Like many things with SARS-CoV-2…there really isn’t much firm guidance or leadership. Everything is approximate and “kinda,” which is a really lousy way to manage a pandemic.

Okay – let’s talk about the student spacing, and let’s go at it like we normally do – treat it like a STEM problem.

Students and Their Bubbles of Safety

There are about a million caveats going forward, but chiefly, again, we’re only talking about spacing out students. We’re not going to get into getting kids into and out of the rooms, sitting still, passing materials around the class, sanitizing the rooms during the class change time, or any of the million other issues that you can spot with just a casual glance at the CDC guidelines.

Deep breath. Just the spacing. Specifically – how much room do we need? Six feet apart. Desks and one assumes., the students should all be six feet apart from one another.

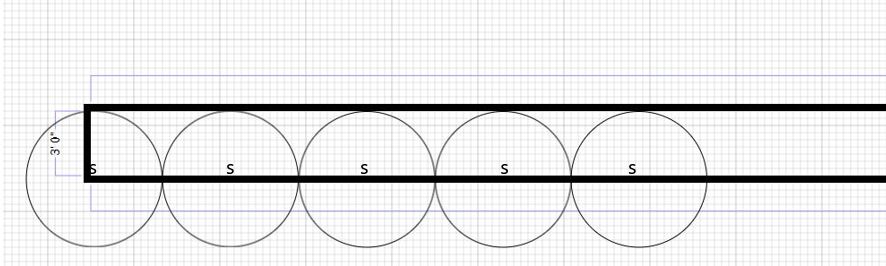

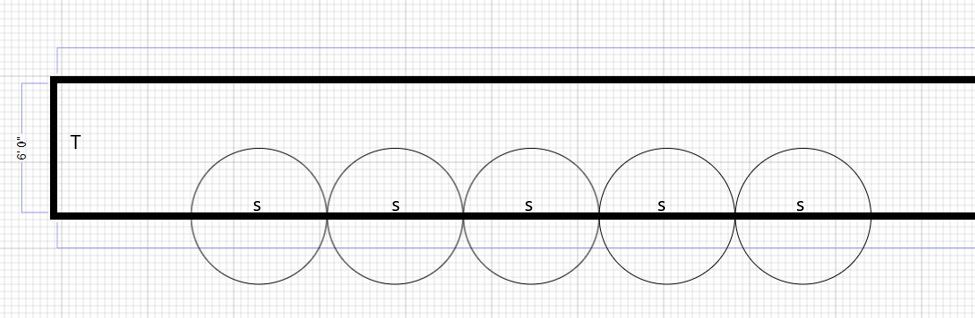

Let’s make this simple – for each student, you need a circle with a radius of 3 feet. That will be the most efficient use of space. The radius is half of a circle’s diameter, so there’s our spacing of six feet apart.

Of course, the area of a circle is ㄫr2, which means that each circle around a student will cover 28.3 square feet. I’m assuming that the rooms have ceilings of normal height, so we don’t need to overly worry about the volume of the sphere, just the area of the circle. We are making an assumption that the students are about as thin as a piece of string, just because it makes the calculations easier. Students, at least in my experience, are not as thin as pieces of string.

Viewing students as six-foot diameter circles that can only touch at the edges and never overlap – now we’ve got a geometry problem. How can we arrange the circles in a classroom? This is just geometry. With additional design considerations of pathways for the students to walk, as well as pathways for the teacher to move through, and an area for the teacher’s desk, etc.

There are two approaches we can take with this, and I’m just going to go with the simpler one – rows of students. How many students are in each class will vary from school to school geographical region to geographical region, but for me, I’m going to go with my number – 30 students. 30 six-foot diameter circles. How can they be arranged?

Arranging My Student Circles

Again, I’m taking the easier approach first – I’m just going to arrange them in hypothetical “rooms.” The simplest of these? One row of 30 students. We can save some room by jamming the first and last kids in the corners and make sure that every student is against the wall, so we only need to worry about 3 feet of their 6-foot diameter for the room’s width. It would look something like this.

This room is 174 feet long. Oh, and there’s no room for a teacher.

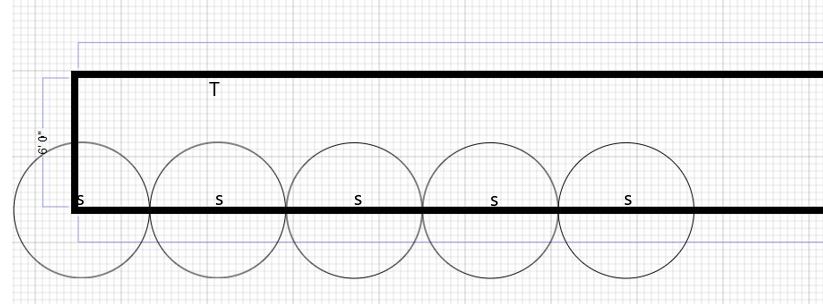

Of course, you notice the problem – there’s no room for a teacher to get in there (I’m leaving the mechanics of how students get into and out of the rooms out of the mix for this…). If we add a teacher space, we need to make sure they stay 6 feet from the student as well, so we can perhaps jam them against the wall opposite the students and assume the teacher is as thin as a string, and it would double the width of our long room, making it look like this:

Still 174 feet long, but with room for a teacher to walk along the far wall – as long as they stay flat against that far wall.

Let’s talk about room areas – a room with 30 students, using 6 feet each would just be 30 x 6’ long, but remember, our first and last students are in the corner, so that saves us 3’ on each, so the room’s length would be 174 feet.

Okay – so:

Long room without teacher space: 174’ x 3’ = 522 ft2.

Long room with teacher “gutter”: 174’ x 6’ = 1044 ft2

Adding teacher space, let’s be just a little generous – add an additional six feet to one of the ends of the room, like this:

Look at all that luxurious room for a teacher – maybe a squeaky chair or beat up desk could go in there! Wait – none of these rooms have doors…

So, the area of a long room with teacher space and teacher workspace: 180’ x 6’ = 1080 ft2

Yeah, I’ve pretty much described a hallway.

From there, again, just talking about arranging desks in hypothetical rooms, it’s just a math exercise with some tweaks, and you can do the variations for:

- 2 rows of 15 students (again, with first and last kids tucked into corners, and all students against the walls on either side of the room), with and without space for the teacher to walk – that would have to be 6’ between the desks on either side, as the rail-thin teacher would have to be six feet from students on both sides. And you can do the calculations with and without a workspace for the teacher.

My numbers ranged from 504 ft2 (students only) to 1080 ft2 (students, teacher space and workspace) - 3 rows of 10 students, with all the above considerations and variations.

- Square footage needed, between 648 ft2 and 1440 ft2, again, depending on if you want a teacher and if you want the teacher to have some room.

- 5 rows of 6 students, with the same considerations and variations.

- Square footage needed: between 720 ft2 and 1728 ft2, with the above considerations.

And then 6 rows of 5, 10 rows of 3, etc, which will get you the same numbers as they did earlier.

But – your eyes are rolling, aren’t they? That’s because:

This.

Is.

Ridiculous.

As far as math problems go, it’s okay – there’s that, but no one is building a school to accommodate students in the COVID-19 future. Schools will have to accommodate students and teachers in existing buildings with their existing rooms of set total square footage, and some with unmovable objects and features. Speaking personally, my room is about 20’ x 30’ and it has two triangular sink stations for lab work about 15 feet from the side wall on either side of my room.

And just like no one is building a new school to meet COVID-19 guidelines, there aren’t many schools that are going to have extra money to swap out lab tables or other multi-student seating for single-student desks. Again – speaking personally, I have two-seater tables set up in pairs, for a total of eight “tables” that seat four students.

Neither the two tables together or the tables themselves will work under the CDC guidelines.

But – as was reported, the administration has “shelved” or “buried” the guidelines for being overly prescriptive. So there’s…that?

Ask any teacher or principal, as well as parents…there’s no easy way to open schools this fall.

Let’s break this down from a personal point of view, and then larger ones.

In My Room…

I just wanted to take a minute and go over the personal side of this since, as usual, the reports being written about what should or will be going on in the classrooms in the coming months rarely if ever include any input from teachers. I am a teacher. I teach Honors Chemistry and Honors Physics in high school – my students are ages 15 – 18. As I mentioned, my classes are around 30 students, but I can pop up to 32. I’m not sure what I do after that, as my room would be uncomfortably crowded, and I would be out of seats, but that’s not what we’re talking about right now.

In all of this, mind you – I’m not complaining. Like thousands of other teachers across the country and around the world, I’ve been trying to wrap my head around how my classes would run once we return to physical school. I’ve yet to come to an answer that works without fundamental changes to what school was like in February of this year.

Just to take you inside my head for a few of the guidelines – this is in no way a comprehensive list – and how I’m trying to figure out how to implement them:

- Six-feet apart. That’s a non-starter. I cannot have as many students in my room as I did pre-COVID and follow the guidelines. The geometry just doesn’t work. And my room is bigger than most. I have no idea how to implement this guideline in my classroom at all.

- Hand washing. I have four sinks in my room, two with soap and paper towel dispensers. I’m lucky. Should students wash their hands as soon as they come into the room and before they leave? 30 x 20 seconds (with no time in between, and thus no social distancing) is ten minutes at the start and end of class for hand-washing. I’m not thrilled with losing 20+ minutes of class time to hand-washing.

Hm – I guess I’d prefer sanitizer, but research suggests that the optimum amount is 2.25 ml. A big “school-sized” container of sanitizer (if you can find them) is about 68 oz, which is about 2010 ml. Students should spritz coming and going, so 60 x 2.25 = 135 ml used by one class. I have three classes each day, so 405 ml used each day for optimum antiviral protection. 2010 ml/405 ml = about 5 days. I’d need a new 68 oz jug each week, roughly. Take that number times about 60 for the number of classrooms in my school – 60 per week, around 240 jugs per month. Again, if you can find them. - Clean and disinfect surfaces. I’ve got three classes, about 30 kids in each coming in during the day. Our school has a five-minute transition time between classes. Being the only common element in the room, I’d have to clean the desks in the room – both desks and seats – during the time between classes. That’s fine – I’m house-proud of my classroom. But my students could not come in until I was done, so they’d have to wait in the hall – six feet apart. Although – I could be cleaning and disinfecting surfaces while they’re waiting to wash hands. That’s a decent use of time.

- No physical labs. Part of both chemistry and physics is learning through inquiry, and for hundreds of years, this has been done with lab exercises and activities. Until we’re out of the woods, physical labs, where students work with partners or in groups – those are done. That sucks on so many levels that would be an article unto itself. There are many virtual lab solutions available (as any lab science teacher can tell you – every edtech vendor on earth came knocking in March), so while the sensation, the uncertainty, and the depth of understanding of a physical lab activity will be lost, the faint idea will remain. Like a shadow.

- Masks Are for Heroes. I’ll be wearing a mask, they’ll be wearing masks. I’m on board the mask bandwagon, big time, and totally okay with them. I do…or will hate that masks block facial emotion – sometimes, there’s nothing better for a student to see you smile, or screw up your mouth when they’re taking a problem down the wrong road, but I can live with masks.

- Meals in Classrooms. I’m not in any way in charge of the logistics of a school’s food program, but this one has me stumped for a high school. I see the idea behind it. My cafeteria is a large, open room with a very high ceiling where about 300 students sit, shoulder-to-shoulder to eat as quickly as they can, without time (300 x 20 seconds) in the schedule to wash their hands before or after eating. I’m not sure about the cleaning up after lunch, occasional spills, the food waste, the additional hand-washing needed, etc. Food allergies could become a serious issue. Not to mention that my room is smaller than the cafeteria, and in order to eat, students will have to remove their masks. See “Ventilation” below.

- Classwork – all digital and virtual. I can’t see how, with all of the precautions we’re being asked to take, we can have any kind of work done on papers that will be collected. This isn’t horrible on the surface – we’ve spent our time since March training kids how to work on a variety of platforms to both produce and submit work online. Communal computers will be a thing of the past, as the CDC’s guidelines recommend that students do not share electronics.

While we’re talking about classwork, any work that has students out of their seats, whether stations for investigation, a distance/displacement walk through the halls, or…anything like that will have to be severely limited and really go under the microscope when I’d want to give it a go. - Ventilation. My room’s okay. Given its position in the building (second floor and without a fenced area on the ground below) my windows do not open. I am protected from ladder-carrying bad guys, Spider-Man and ninjas. My room is a chemistry room, so I have a ceiling-mounted exhaust fan, which is noisy. The airflow in my room is usually pretty good, but there are questions if even ventilated rooms are good enough. Some well-researched contract tracing studies have traced multiple cases of COVID-19 back to infected individuals in well-ventilated rooms. At least this room has windows. My first ten years were spent in rooms without windows and a ventilation system that probably voted for LBJ.

- After school – tutoring, activities, clubs. Well, I figure the latter two won’t come back for a while, but tutoring – that’s a necessity in most STEM classes. That could be pushed to online-only, of course – perhaps teachers and students will have a dedicated video-chat time each school day for help in particular subjects, though I worry about the “always-on” status that teachers have been pushed towards as districts have started to both better understand and encourage teachers to be available to students during non-school hours.

- Teacher Time. My before and after school activity will be different. I’m not the most social butterfly, so I wasn’t always hanging out in other teachers’ rooms before starting, but I would work with my colleague that also teaches chemistry to make sure we are on the same page. I’d also get my mail, eat lunch with my department, and occasionally, during my planning period, check the break room to see if anyone left cookies. All of that will be re-done. I 100% acknowledge that this is the least important part of all of this, but teachers cannot run every single minute of every single day. We need downtime.

Those are the issues that I come up with off the top of my head when thinking about my classes, my classroom, and my day in a very general sense. Not all of them are total game-stoppers, but a couple are the size of my class, and spacing makes things non-starters if my district follows the CDC guidelines.

Let’s blow this up.

Yes, that was a horrible choice of words when talking about schools. Sorry.

The COVID-19 High School

As I mentioned before – I’m just a teacher. I’ve never had a desire to be in administration or in any way be responsible for managing the building or the large groups of people, whether we’re talking about adults or kids inside it. Like any teacher, I’ve butted heads with administration and questioned their actions many, many times. These days – I don’t envy them one bit and feel loads of sympathy for them. They’re being asked to do the impossible. Making a high school work in the time of COVID is Star Trek’s Kobayashi Maru. There’s no reprogramming the simulation or gaming the system. There is no winning this. There is no making everyone happy. Everyone – from teachers to parents to students will have something to point to that is wrong and therefore, as they see it, dangerous. There’s no way to get this right, there are just degrees of “gettiing it wrong” that are going to have to be acceptable.

Just some discussion starters in a loose order of the day:

- Buses. The CDC recommends increasing the distance between students on busses. Most school buses run pretty full. Cut the number of students allowed on the busses by half for instance, and you’ve got to run twice as many. Or twice as fast, Otto.

- Before the Bell. Most schools allow their students to congregate in large areas (our cafeteria in my school’s case). That can’t happen anymore.

- Screening at the Door. Who’s checking temperatures of the students coming in and asking if they’ve had contact with a known carrier, or are feeling sick themselves?

- Masks. Do students provide them? Does the school? What about in a Title I school where the majority of students receive free or reduced lunch (a school’s indicator of poverty)? Do schools require all students to bring their own masks, and if so, what do you do if some are clearly sub-standard? How many masks per day should a student get or be expected to wear? This leads us to…

- Masks Part 2: Do schools have the authority to require students to wear masks while on school grounds? What happens when a student refuses to wear one or insists on wearing one wrong (nose out)? What kind of disciplinary offense is that? Are they sent to in-school-suspension (most often a small, otherwise unused room managed by an adult)? If rules call for the defiant student to go to ISS, and they continue to refuse to wear their mask while there…the situation has escalated. What then? Well, we can move on to…

- Masks Part 3: Sometimes students get in physical altercations. Masks will not remain in place during such times, and the crowd of students watching free entertainment will not be maintaining social distancing. Teachers working to break it up may lose their masks as well.

- Class change. Staggered class change to limit the number of students in the hall at any one time? Double the time for changes, given that teachers will most likely be disinfecting rooms?

- Spacing in rooms. I know I mentioned this in talking about my rooms, but my school has plenty of rooms that are half the size as mine with the same count of 30 students. There’s just no way to make that work and follow the guidelines.

- Who’s Teaching? Not all the teachers who were teaching during the 2019-2020 school year are coming back. I’m not talking about our normal attrition and retirement, I’m talking about teachers who will see this as a risk they didn’t sign up for, teachers who are close to retirement, the 29% of teachers who are in their upper 50s and 60s, teachers with underlying health issues, and teachers for whom this is just looking like too much. Trust me – the jump online has been a stress test for all of us, and not everyone handled it as the stories about “hero teachers” who drive to student homes and make videos and cartoons every day for their kids might make you think.

Again – full sympathy for the school’s administration – how do you hire for new faculty during this time?

Oh, and this isn’t even considering the President’s suggestion that as schools reopen, older and more vulnerable teachers should be sequestered somewhere, and not be in contact with larger groups of students. - Lunch. Mentioned earlier, but take my concerns about a classroom and multiply it by 70 or 100. That’s an amazing logistical challenge.

- Sick Kids and Adults. The CDC recommends something that teachers have been begging for years to implement: sick kids go home. If you’re trying to keep a school COVID-free, you cannot have sick students (no matter what the disease) coming to school. So we’ll need temperature-checkers or screeners by the door, as well as the authority to quarantine kids who show up with fevers or other symptoms. Oh, we’ll need a quarantine room, too – set apart and regularly disinfected.

Yeah – sometimes, kids are sent to school sick because of child-care situations (again, think of Title I schools), but in a COVID world, we can’t allow for that student to be in their classes – or we need someplace to put sick kids where they can stay in the building during the day, and not infect others if staying at home is not a possibility.

And teachers – we work sick all the time. It’s our worst badge of honor to talk about things like telling your kids you’ll be right back, running to the restroom, throwing up, and then returning to class. Every teacher has worked a day when they were so sick that their students told them that they needed to go home.

What do we do with those teachers? In many districts, missing a day of teaching means you have to pay for your substitute out of your own pocket – not to mention, a sub will rarely move your class further ahead on the path you need them on, and making sub plans is tough (and tougher when you’re feeling lousy) – so you work sick. - Is the Teacher Sick? As the CDC recommends, we’re going to have to have regular testing, temperature readings, and more. Some of you may be taking part in daily surveys or having screenings at your place of work. That’s going to have to become a regular thing at schools. This seems like an appropriate place to point out that due to budgetary issues, many schools do not have a full-time nurse, which is to say that one person could handle an entire school in the ear of COVID testing, precaution, prevention, and possible treatment, anyway.

- Substitute Teachers. Who’s going to want to do that job in the world of COVID?

- What Classes Live, What Classes Die? Not all classes that students took pre-COVID are variable in the COVID Era. At a webinar on the subject of COVID, the American Choral Directors Assoc./National Association of Teachers of Singing said that there is no safe way for choruses to practice until there is a vaccine or 95% effective treatment in place which, they stated, could mean 1-2 years. Most likely band class will be the same way – too many students, too close together – instruments going into and coming out of mouths, and the spit – oh, the spit of brass instrument (former tuba player, here).

Likewise, courses that require hands-on sharing of resources. Shop, foods, engineering courses based on fabrication, and making. Driver’s education. How can those work? - Sports, Teams, and Extracurricular Group-Based Activities. Gone. We don’t really need to spend time on the whys, do we?

- No Shows. Prior to my own district/state calling things off, we were starting to see students staying home – some of whom had underlying health issues, as well as those who felt strongly, or more strongly about social distancing and quarantine than the district did to that point. Just as I am sure we will not see all of the teachers return, I can guarantee we will not see all of the students return for valid, unshakable reasons which would result in a tough legal battle that no district will have the finances or stomach for if push comes to shove.

- Liability. Who’s responsible for the medical treatment if the person was told they had to (or were urged or pressured) return to school (student or adult) becomes infected? We’ve all seen shockingly stringent measures being taken in locations that are opening back up, and school districts are no different. For me to go in and get my personal belongings in my own school, my district has set up a whole screening, temperature check, sanitation, traffic flow system to prevent contact and/or infection. I’m taking that as an indicator that they, in no way, want to be seen as liable if a staff member is infected. I don’t see that weakening for the fall. Will attending or working at school now include a waiver stating that the individual will not hold the district liable? I know, I know – flu season, but COVID is not the flu.

- “That school.” I’ll argue until my dying breath that one of the reasons why COVID wasn’t so bad in my community is that our Governor shut the schools down early. No principal wants to be leading the school where the outbreak happens, and no superintendent wants to be known at the leadership of the district that blew it. Jokes aside, the numbers aren’t on the side of everyone. It appears that COVID’s mortality rate has come down from the 5-ish% it had earlier this month to around 1.5%. That means that an outbreak at a school of 100+ people – someone has a very good chance of dying. Enrollment at that school will bottom out, and no one will come to class once even a rumor of infection starts. The CDC guidelines recommend closing the school for a short period (perhaps a couple of days) to clean if an individual who tests positive for COVID-19 is found in the school. Thanks to the potentially toxic mix of misinformation and false beliefs circulating about the virus, coaxing students back to school after a positive test in the building, or rather, coaxing parents to send their students back to school will be difficult at best, and will require messaging about the virus that will counteract what parents and students have heard.

- Optics and Staying in Your Chair at the Table. Related to the “that school” point, as the past couple of months have regrettably shown, virtually everything about this virus can take on a political angle. School boards are elected positions, and in many districts, superintendents serve at the pleasure of the Board, while principals serve at the pleasure of the superintendent in many cases. I’m not saying that decisions will be made with an eye on keeping certain individuals or groups of voters happy, but I’m not saying that they won’t either. No one wants to lose their job or be voted out over a bad decision – and that adds pressure and stress to every decision in an atmosphere where decisions are made minute-by-minute.

Just want to lie down now? If you’re feeling that way now, you’re well past me. I’m normally on the ground after thinking about my own room.

The COVID-19 School District

Take all of the above – my personal concerns, the concerns for a school, and then add in middle schools, elementary schools, and if you’re lucky, district-run pre-K centers.

I teach high school and have an aversion to any middle school; or elementary school-aged child that isn’t my own, but I’ve had it from reliable sources that younger kids like to touch and hug. And don’t always do what you tell them to do. Or have the cognitive capacity to understand that they need to wear a mask all day.

They’re not the neatest of eaters.

Sometimes, they lose teeth (source: my father taught first grade).

Sometimes, fluids.

Sometimes, runny noses.

Carpets in classrooms, cubbies, reading circles, beanbags…all those elementary and middle school (and sometimes high school) seating arrangements that were cool and neat, and made you think life was unfair if you didn’t get that teacher.

Okay – I’ll stop picking on elementary and middle school kids…not because I want to, but because I have to get to more…

There are whole swaths of school district operations that will have to be scrapped and re-imagined in the world of COVID:

- Students with special needs – from the very mild to the very severe, requiring an adult assistant for day-to-day functioning in a school. As some groups and parents have pointed out, schools are required by law to provide services for students that request them and show a need for them – something that has been a struggle with the transition to online classes.

- English Language Learners – every problem that was mentioned above, but in a language other than English. No big deal? Many schools and districts have students that speak a language which isn’t one of the languages that are supported for the majority of ELL students.

- Schools in high-poverty areas. These schools have it tough on any given day. In the world of COVID, even the smallest challenges of daily operation are likely to balloon into larger ones.

- Inequality. Don’t let this one slide by – this is multifaceted and will be part of virtually every other issue that districts have to face, whether it is directly addressed or not. Some schools have PTAs with hundreds of thousands of dollars available for spending by the school as it sees fit, some have literally none. Some schools will have plexiglass enclosures for front office staff, others will have to choose between that and something that more directly affects students. The stark differences in food security, shelter, heat, social contact, digital devices, wi-fi, and on and on seen between students in different schools and areas of the community in most districts are often breathtaking. The last two months have, if anything, deepened the divide.

So What Do We Do?

I don’t know.

I don’t know.

While this may feel like a list approaching some kind of comprehensive nature, it’s not. It’s not even close. I’m sure you can come up with half a dozen more without trying, and a full dozen if you put your mind to it. And also – to be really clear, I’m not listing this out to just point out problems or complain. That’s really not how teachers work. We fix problems. But what’s here is – more or less – what’s on every teacher’s mind now:

“How in the world are we going to reopen?”

Followed by a lot of brain cycles of trying to figure out problems that are specific to their classes or rooms. And then – the lying down on the floor. And, if I can speak for every teacher, I think we all have two lines in mind for returning to school, the “alright, I guess so…” line of precautions that are taken that, while we’re not 100% comfortable with, we’ll agree to work under, and the “nope” line of precautions that we personally feel don’t meet a standard under which our health can be reasonably guaranteed.

Schools aren’t businesses, they’re not hospitals, or parks, or libraries or any other kind of space for which rules have been laid out. Schools are schools. They’re unique, special places. Abused a lot lately, but that’s something those of us inside are used to. Schools have an infinitely important job – we make the future. In doing that, we’ve got a massive number of stakeholders invested in the outcomes of the schools, the operations of the schools, and every decision that goes into their management. And the bulk of those stakeholders are parents who will go to any length to protect and get the best for their child.

If nothing else, think of this as a list of impossible decisions. There is no way that schools will open so everyone is happy. Welcoming all the students back with no rules is a non-starter. Engaging in all of the CDC guidelines seems well, to quote the administration, “overly-prescriptive.” There are ideas in those guidelines that just cannot work.

But at the same time – many districts (mine included) pointed at the earlier CDC guidelines as their true north, as well as their justification for why they weren’t shutting down early on. You don’t want to, as an organization, appear wishy-washy and come across saying that while you listened and strictly adhered to the CDC guidelines last time, we don’t really have to this time because…x, y, and z. So districts need not only a good plan, they need really good messaging to explain the plan and why it’s the best one for the situation. There are a lot of stakeholders to convince.

Denver has announced it is flirting with the idea of a combination of online and in-person classes, perhaps alternating days with some students coming in one day, and another group the next. On the surface that seems like something that can work, or perhaps a plan where those students with the ability to stay home and stick with online learning, while those for whom school is, in part, a child-care solution or more importantly a reliable source of food (and in some cases, heat, safety, and shelter), they come to physical school. It’s a seductive idea since many of the issues with the guidelines listed above can be reasonably addressed “we just need fewer students” is put on the table.

But digging into that idea, it has problems – it shines a brighter light on inequality as the “haves” can stay at home, while the “have nots” must travel to school – and potentially face an increased risk of infection. It could also work to increase the teacher’s workload, making them teach both online and in-person, and then having a session to help those who need assistance but don’t come to physical school. Unless students coming into school are just doing the online material – in a physical setting. Which just makes that inequality thing sting a little more.

Oh – and some classes, some schools, and heck, some districts would be empty and others would be full if the plan to adopt those who can stay home and those who can’t come in. Speaking from experience (as I’ve taught in both schools), I would have fewer students than my wife would on a daily basis because my school is not Title I. If we go back to the idea of exposure, teachers at Title I schools would have more students than those at non-Title I schools, and as a result, would face a greater risk. Would that even be considered? Compensated?

And when the rebound happens – when we have to go back into quarantine, what do we do then? Is there a plan for how we do this – and do it better – next time? We can’t focus all our energies on a reopening plan so that we forget to plan for the next time we stay home in a community or state.

What do we do?

If you’re like me, you’re exhausted, and not just from reading an ultra-long piece about reopening schools. You’re exhausted because your mind has gone down so many roads, only to find that they’re not roads by blind alleys. There are no easy answers. There’s no quick fix, no “break glass in case of emergency” box with a list of instructions inside. There are no answers that will make everyone happy. Just get that out of your mind right now, whether you’re a parent, a teacher, or a student. When schools – your local schools – announce how they’re going to reopen, there will be some good ideas and some bone-headed ones with clear flaws. That’s the nature of this beast. But the schools have to reopen.

I could go on and on about how public education’s stakeholders need to step up, but honestly, I don’t know what could be added. I urge you to – however possible – weigh in on or at least show support for your local public education system, but again, this is an impossible situation. I could also go on and on about how we can take this crisis and make schools and education better. But there are others who can do that far more eloquently than me.

Communication through it all is going to be key as well. The audience listening to anything a school district has to say about reopening will be at the same time scared, defiant, misinformed, well-informed, sympathetic, antagonistic, marinated in mistruths and conspiracy theories, scientifically literate, and scientifically illiterate. An authoritarian tone will not reach everyone or play well. Stakeholders who don’t feel like they know what’s going on are not happy stakeholders.

Common to all of this is the fact that decisions need to be made, and decisions are going to be made.

There’s no “normal” to go back to. Things cannot be the way they were. It’s just a brave new world that we’re going to have to somehow make work. The future is too important for us to fail.

Teacher? Parent? Student? Stakeholder? Have some ideas or want to discuss what you read? How much can you think about this before you want to lie down? Join us over at our Facebook page to join in the discussion!