So here we are. Masked in public. Or, it’s recommended that we should be wearing masks.

On April 3rd, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention made the recommendation that everyone should wear masks in public spaces when they need to be around other people. But that

Why Should I Wear a Mask?

First and foremost, wearing a mask is to protect others from the stuff coming out of your mouth when you talk, cough and just breathe.

“But I’m 100% not sick.”

Awesome – keep washing your hands and following safe practices to keep it that way. But you might be infected and not know it…and still spreading virus (“shedding” as it’s called). You may be asymptomatic, and never get sick but still carry the virus, or you may be pre-symptomatic (not showing signs of COVID-19 yet) and spreading the virus.

A mask will reduce the number of viral particles coming out of your mouth from getting to other people. No matter what your mask is made of, some of the particles will land on the fibers and stay there.

But – you may not be 100% not sick, and just don’t know it. More on that coming up.

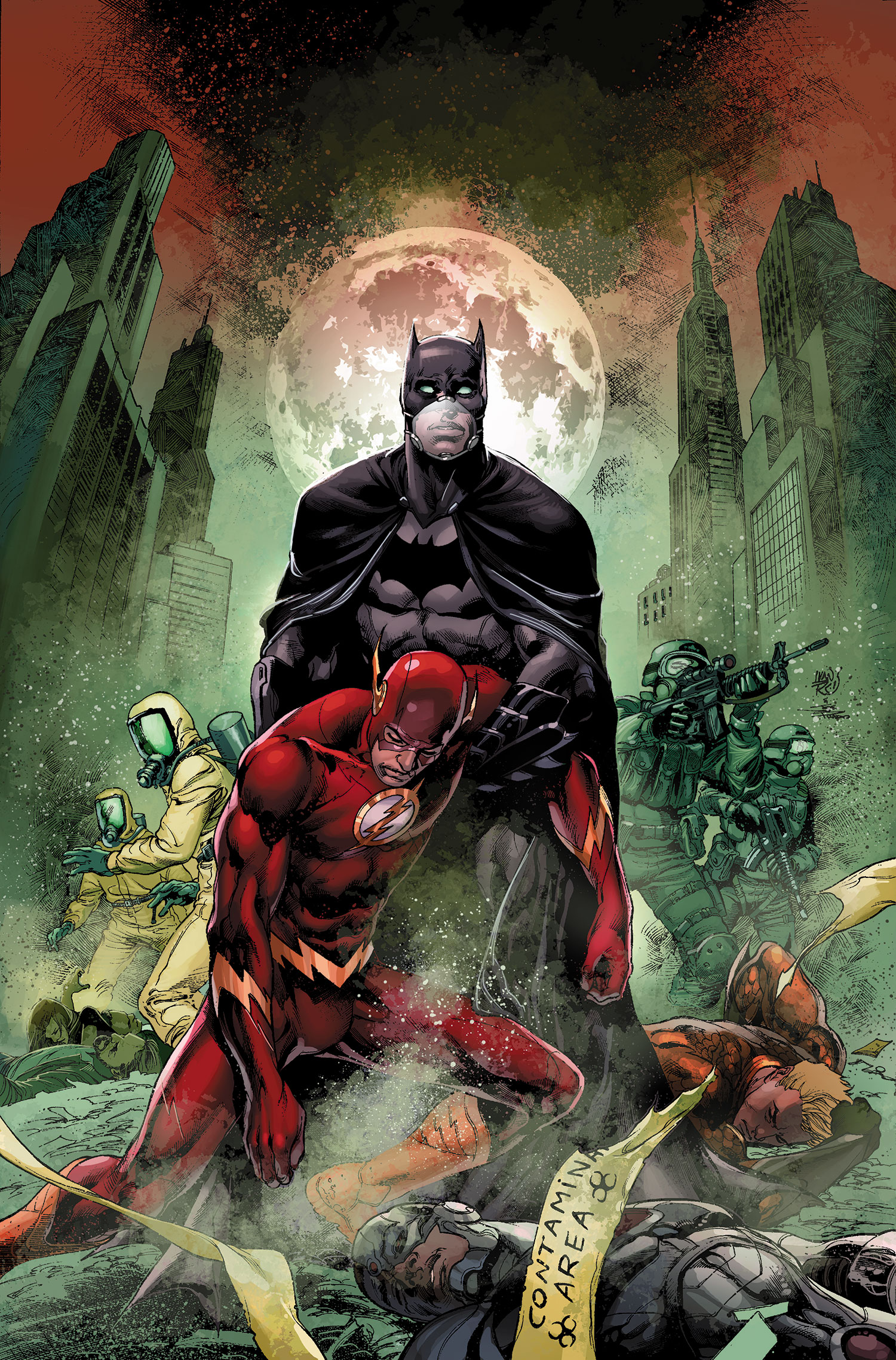

Batman was wearing a mask on top of a mask back in the day of the Amazo virus…

Okay – secondly, a mask, any mask will work in reverse to an extent – some of the viral particles in the air will land on the fibers of the mask and stay there. The problem there is that when you breath in while wearing a mask, a bunch of the air comes in from around the edges of the mask, rather than through the mask.

Again, in this case, masks are intended to protect the environment from you, not you from the environment.

And there’s also a social aspect as well. As science writer Ed Yong told the Radiolab podcast recently, “The mask is not just a medical device, they’re also a social device.” Wearing a mask sends a message, depending on how many people are wearing masks.

“If only one person is wearing a mask in a society that traditionally doesn’t wear masks, it’s very easy to think, ‘Oh, that’s a little weird.’ Whereas if everyone is wearing masks, it starts becoming more of a sign of ‘We are all in this together. We want to protect each other.’ Even if that effect is small, I think that is a powerful signal.”

Yong’s point is the big one with wearing masks. You’re not doing it for yourself. You’re doing it for other people. To take care of other people, and make sure they don’t get sick from you.

Wait. Didn’t “They” Say Something Else Last Week? Why Should I Listen Now?

Yes. Yes they did, and no one’s hiding that or trying to convince you that the message from health authorities was something other than it was. Early in the days of response to COVID-19 in the United States, the message was clear – don’t hoard masks meant for medical use, only use them if you yourself are sick, at risk, or caring for someone who is sick – and you don’t need to wear masks to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection. The CDC, the Surgeon General of the U.S., and Vice President Mike Pence all said they were unnecessary.

Seriously people- STOP BUYING MASKS!

They are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus, but if healthcare providers can’t get them to care for sick patients, it puts them and our communities at risk!

https://t.co/UxZRwxxKL9— U.S. Surgeon General (@Surgeon_General) February 29, 2020

The recommendations were coming at a time of stores rapidly selling out of masks, so the message reaching the public was decidedly…mixed.

What changed?

Despite the pronouncements in early March that masks were not needed by the general public, the discussion and debate over their use never went away, and by late March you could tell that the attitude was moving towards using masks and, well, here we are.

The first thing that “changed:” as we’ve all heard many people will become infected with COVID-19 and never present with any symptoms other than a mild fever and slight cough before recovering – if they even show any symptoms at all. But research suggests that these individuals – perhaps even you – can spread the virus while not showing any signs or symptoms of infection yourself. Or, on the worse side of that infection coin, people infected with SARS-CoV-2 may be pre-symptomatic and on their way to developing a full-blown or a mild case of COVID-19. During this pre-symptomatic state, sometimes lasting up to two weeks – these individuals also can spread the virus.

These individuals are the so-called “silent spreaders,” and have been identified as being responsible for a significant chunk of spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore and China as well as cases in the United States and other locations all over the world. Also, the silent spreaders may be what cause some places to bounce back and forth between lockdown and open as time goes on.

And combined with that is the idea that SARS-CoV-2 may do more than just ride on droplets from an infected person to a non-infected person.

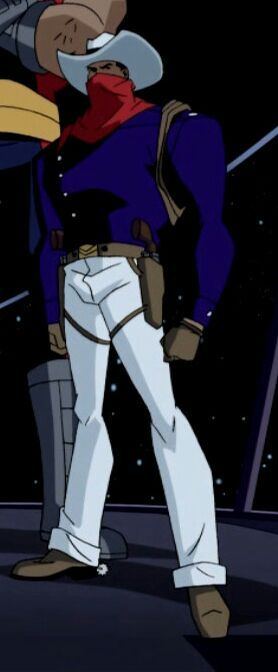

The Vigilante was wearing a mask back in the day…

The second thing that “changed:” do SARS-CoV-2 particles spread through the air?

That’s complicated. And not settled science yet.

When we breathe, cough or talk, we release two types of particles: droplets and aerosols.

We all let out droplets of varying sizes whenever we open our mouths. Those droplets can be big, say, like with a sneeze – visible to the naked eye or microscope

Adam Savage sneezing for science on Mythbusters

(c) Mythbusters

Or very small, like just when we’re talking. But they’re always there. Our lungs are humid places. Nothing comes out of them without a load of moisture. Droplets. Or as some gross folks like to call it, “mouth rain.”

Our current six-foot rule comes from research done examining the spread of disease among airline passengers – how far away from the known person with the disease were people getting sick? Answer – two rows in front of the sick person and two rows behind. About a six-foot bubble. Roughly.

The CDC accepted this result and adopted the standard that six feet was about how far a droplet can travel. But the tragic case of the church choir in Mount Vernon, Washington, where 60 choir members practiced (skipped on hugging and handshakes, and kept their distance) changed the idea of COVID-19 moving just by droplets. Of the 60 choir members, 45 members were diagnosed with COVID-19 and to date, two died.

This story, which came out near the end of March was enough to convince many health officials to reconsider the “droplet only” spread theory and assume that there was at least some aerosol transmission going on as well. But the aerosol transmission has been tricky to prove, and for good reason. The droplets that are in an aerosol are so small they can float, rather than drift to the ground.

Experiments done in a lab setting show that the virus can remain viable in aerosol for an hour or more, but translating that result into real-life, “people experience” has proven tricky. Meanwhile, experiments done at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (whose hospital is specially designed for handling airborne pathogens) showed virus particles more than six feet from patients with confirmed COVID-19 cases, as well as in the hall of the hospital – although one of the researchers on that study, Joshua Santarpia recently told Radiolab that he’s not sure the hallway finding means that it was floating in the air. It could have been, Santarpia explained, carried on clothes.

Santarpia was also on the team that went aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship which found SARS-CoV-2 pieces and particles all around, on virtually all surfaces and in the air. But to be clear – on the cruise ship Santarpia found genetic material from the SARS-CoV-2, not whole, “live” virus particles, ready to infect the next healthy cell that they found. And that’s important – this SARS-CoV-2 is not immortal or invulnerable. It’s somewhat fragile – and it does eventually fall apart in the environment.

Mask on top of mask…layering is key.

And in all of this, of course, is how much virus does float in the air. Is it at high enough numbers to infect a person? Under a certain threshold, there are just not enough virus particles to mount a successful infection of a person. Understandably, no one wants to play around with that number if they don’t have to, but still.

But there’s no solid answer on whether or not live virus travels as an aerosol, and if it does – how far that aerosolized virus can travel.

Hence the mask when you must go somewhere. The mask will stop “some” to “a lot of” those particles from getting away from you – just in case you happen to be asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic. To drive that point home – the finding about the asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic spreaders…that’s what came to light. That wasn’t known early on when we were being told masks weren’t necessary.

A natural question to ask would of course be – “when will they change their minds again?”

“They” probably won’t. Social distancing, hand washing and masks in public are going to be the strongest defense we can mount against this, as a population. And most likely be around for a long time.

What Should My Mask Be Made From?

Barring scoring an N95 mask, most people are left up to their own devices of making their own mask.

First off, the caveat: no mask will be 100% effective against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. A mask’s ability to “catch” SARS-CoV-2 virus particles depends upon the size of the pores (spaces between the fibers) in the mask and the size of the virus itself. SARS-CoV-2 is reportedly 120 nanometers (nm) in size – 120 billionths of a meter – which is large as far as viruses go.

The decision to recommend masks was made from an abundance of caution. And when you’re working under those guidelines, something is better than nothing. A 2013 study showed that a cotton t-shirt blocked about half of the virus particles coming out of the mouth from a cough, while a more tightly weave of a tea towel stopped around 72% of virus particles.

And now you’re thinking, “A t-shirt over tea towel…122%!”

Yeah, okay – calm down.

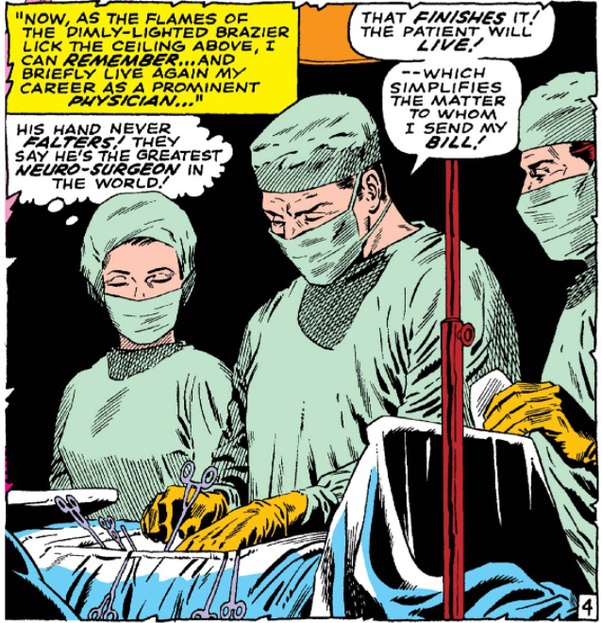

The keyword here is layers. Look again at any picture of a surgical/medical mask, or that one Dr. Strange is wearing up top. See those horizontal pleats? Those are layers of material folded one over the other. One fold of fabric is meh, two folds of fabric is better. More folds or layers of fabric – it just gets better. Up to the point you can’t breathe through the mask, of course.

A tightly woven layer on the inside with a flashy, distinctive pattern on a more loosely-woven fabric on the outside? You’re good to go.

What are the good fabrics? 600-count woven sheets and pillowcases, for one. Flannels work well, along with the tea towels. Single-layers of wide-weave material, such as scarves, bandannas and material designed to be stretchy (you’re opening the pores in the fabric wider as you stretch it) are better than nothing, but layer.

When in doubt, hold the fabric up to the light. If you can see what’s behind it or see the weave of the fabric – keep hunting. A study from Wake Forest Baptist Health found that a tightly woven cotton, such as that used in quilting can do a better job than a surgical mask.

Masks protect the environment from you, not you from the environment.

Adding non-fabric materials to the layers of fabric appears to work as well – although some things such as HVAC filters and vacuum cleaner bags are seriously not made for this purpose, and may release fibers of their own material as you breathe in. Simpler inserts, such as tissues, dry cleaner wipes, and even coffee filters all fall into the “better than nothing” camp.

But remember – fold and layer – and make sure you can breathe through it.

Need some ideas? Check out Wired for three designs, including a no-sew one.

Remember, when it comes to a mask, something is better than nothing.

Okay, So I Should Wear a Mask. Got it. All the Time?

No. Not all the time.

Wear it when you go out into public, or will be around other people: grocery stores, pharmacies, those who must work. Your home, your yard – safe zones. The air is not poisonous.

But get into the habit of carrying one around.

Probably overkill, Sandman

Make sure your mask is snug and won’t move it around. If you’re driving, put it on just before you leave your car if possible.

But remember, once your mask is on, do not touch it. You’re going to want to. Don’t. Your nose will itch, your face will itch. It’s going to slide a little. Don’t touch it. It’s there for a reason.

As soon as you get home, or back to a safe zone, take your mask off by the straps, put it in a “dirty zone” of stuff to be washed soon, and then wash your hands. Treat your mask like underwear – or how you should treat underwear – use it once and wash it. Or change it out whenever anything happens that makes you want to change it. That goes for underwear, too.

Care and Cleaning of Your Mask

If possible, have at least two masks – one that’s in the wash or drying and one that is ready for use. Again, when you’re done with it, take it off by the straps, put it directly in the washer or soapy water, or in a “dirty” pile.

For washing your mask, hot to warm water will be fine (along with detergent) in a washing machine (you may want to wash them on a pillowcase or laundry bag so the straps don’t get tangled), or you can hand-wash them with soap and hot water. Soaking and/or boiling isn’t necessary.

But – remember, just like your clothes, every time you wash a mask, you’re wearing it out a little bit. Your two masks that you start this period with will not be the same two you end it with.

So – masks. Ultimately, without a government mandate, and essentially no chance of one coming that everyone has to wear a mask, the choice is yours to wear or not to wear. But think again about the reason to wear one – you’re not doing this for you. You’re doing this for everyone else in case you’re asymptomatic (as someone with the choir in Washington was) or you’re pre-symptomatic (which has been the case in many community spreading incidents around the world).

And – yeah, it’s a pain. It doesn’t feel right. But what does wearing one in public communicate? Wearing a mask in public says, “I care about you, and don’t want you to get sick. We’re in this together, and together, we’re going to get through this.”