Multiverse this, multiverse that.

There was a time when the idea of multiverses was special knowledge held only by comic book fans and physicists. There’s a combination for you.

Now, as a high school science teacher, I get a weird thrill that my students – and everyone else – knows, or at least has an idea what a multiverse is.

Or do we? Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, Everything Everywhere All at Once and Rick and Morty all lean heavily on the most common view of the multiverse: that every decision branches off into another universe and another and another. As a result, an uncountable number of universes exists. That’s the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI), suggested in 1957 by Hugh Everett III.

Everett was a quantum physicist (and dad of The Eels’ Mark Oliver Everett who made a documentary about him called Parallel Worlds, Parallel Lives) who suggested the controversial idea as a robust solution to a problem in quantum physics. That problem – the smallest bits of matter exist in several states until observed. Once they are “looked at,” one possibility locks in, and the others…vanish. In MWI, all the particles in the other states still exist, they’re just in other worlds.

Since we, as macroscopic beings, are nothing more than collections and collections of quantum particles, the somewhat wild extrapolation goes, what’s true with particles would be true with us, and even bigger stuff. If this is sounding like Schrodinger’s Cat being both alive and dead until you open the box, that’s a good hook to hang it on. Open the box and the cat is alive means that in a freshly-created parallel world, another version of you just opened the box and the cat was dead. Driving down a road, and you flip a coin which tells you to turn right, another version of you flipped the same coin, got a different result and turned left.

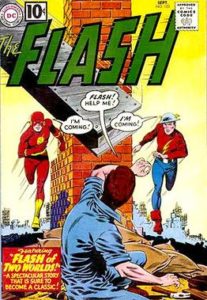

Flash #123, featuring “Flash of Two Worlds,” and kick starting multiverses in comics. DC Comics

Obviously, this is the DNA of Marvel’s What If? Star Trek’s Mirror Universe, the Spider-Verse, The Man in the High Castle, DC’s Multiverse and countless others. While it’s a tough claim to say that comics invented the concept with “Flash of Two Worlds” in 1961’s Flash #123 (that’s where the “modern” Flash, Barry Allen met the Golden Age Flash, Jay Garrick, who lived on a different earth), it certainly popularized the idea. The MWI view of a multiverse is now a part of every major comic book universe, as well as dozens of other major franchises and properties. It’s easy to see why. The MWI is often fresh and fertile soil for new stories, and a playground for creators to recast characters in different ways, charting new lives after different outcomes to previous events.

Many Worlds is the multiverse that virtually everyone knows. But that’s just one version of a multiverse, and it’s not even the easiest one to explain.

Time to dig in. But one quick note – the idea of a multiverse isn’t a scientific fact. There’s no proof, and you’d be hard-pressed to find a scientist who has an idea for an experiment that would be able to provide it. Along with that, not every scientist is sold on the idea of a multiverse – there’s no discipline-wide agreement on the ifs, whats or hows. Some researchers are dismissive of the idea, and some see multiverses around every corner.

The two leading advocates for multiverses today are physicists Brian Greene and Max Tegmark. and while they share some similar concepts, they’re not in full agreement. Greene suggests between nine and eleven different types of multiverses, while Tegmark settles in around four distinct versions. A shared view among advocates is that the multiverse is more than just conjecture, but rather a prediction of specific theories in physics.

For the sake of discussion, we’ll set the skepticism aside and explore the broader categories.

We Live on a Quilt. Or in a Bubble…

The Universe is getting bigger. Space is expanding since the Big Bang and continues to do so, getting faster as it goes. But being clear, the Big Bang wasn’t an explosion. In 1979, physicist Alan Guth proposed the theory of cosmic inflation which explains how (and how quickly) the universe grew after the big bang. Spoilers: really, really fast.

Guth’s theory has been shown to agree over and over again with very precise observations taken over the decades since its introduction. Currently, the inflation theory of “nothing-to-something-as-big-as-the-universe-in-an-instant-and-still-growing” has widespread support and is seen as a viable model of what happened after the Big Bang.

Take inflationary theory at its surface value, and the simplest form of a multiverse comes to light – we can only see/travel/experience so far in any direction. Currently, our observable universe is what we can “see” sitting in the center of a sphere with a radius of about 46.5 billion light-years. That’s ours. Move the observation point 46.5 billion light years away, and there’s no reason to think that the universe just stops over there. That observer’s point has a different observable universe than we do. Put the point outside of our observable universe, and we’d never, ever see them – the universe is expanding faster than we could travel there.

An illustration of the observable universe. Anything outside is functionally in another universe. Image, Pablo Carlos Budassi, NASA

Each “observable” universe is functionally an alternate universe, cut off from all the others. In explaining this version, the idea of a patchwork quilt comes out. Patches side by side – universes that are next door to one another. A patch that’s five patches away from another – no connection, no communication, no information can be shared between them. This idea of a multiverse isn’t so much a quantum physics version as it is geography.

Another multiverse theory that goes along with this is that as the universe (the larger cosmos, not our bit, necessarily) expands, it stutter-steps, pauses or otherwise has a fluctuation in energy. These fluctuations could be the root of Big Bangs, forming a “bubble” in the larger cosmos. Inside the bubble – a universe. Inflation continues, leaving empty space, and “hiccups” again farther away, forming another bubble, and on and on.

Give it time and space, and the larger cosmos could resemble a table with marbles scattered on its surface, or even a foam – each bubble containing a universe. Add the idea of the universe being infinite to this, and there will be repeats of patterns. Another earth just like this one. Another you. Another me. A world where we’re all speaking German, because the Allies lost World War II. A world where Spider-Man goes to the movies and watches films of normal, boring people without powers.

There’s also no reason that every patchwork universe or bubble universe would have the same physical laws and constants. Or dimensions. Also – within a “bubble” of a universe, you may have a patchwork quilt multiverse. That is, the bubble is big enough to contain multiple universes in itself, while being just one small universe of a larger collection of universe bubbles, floating in a cosmological foam.

Feel small yet?

Of all the versions, this idea of a multiverse can make the most sense for many – it’s just inflation theory and quantum field fluctuations, both of which are (we’re pretty sure) real things. And it may just expand forever and ever and ever, creating more and more universes as it goes.

But this more realistic version of a multiverse means there’s no quick fix to travel between them. We’re not sitting in a soup of infinite universes all around us. There’s an insurmountable distance between this universe and the next. You can’t get there by going through a door that you never noticed before in the back of the wardrobe.

Branes and Bulks

Another view that starts to walk into the theoretical side of things and brings in string theory posits that universes are like slices of bread in a loaf. The universes, called “branes” are embedded in the “bulk” – higher dimensional space, with more than the four dimensions we’re used to.

In this model, branes line up like slices of bread, or sheets hanging on a line. Matter is stuck to its brane, but gravity, Greene suggests, may be able to leak from brane to brane like tentacles. The idea about gravity is controversial, but its proponents use it as an explanation as to why gravity is such a weak force in our universe, and (so far) has no particle mediating its effects, like photons that carry electromagnetic force. Gravity is a puzzle in our universe because it’s not from our universe, but rather, the effect of something one brane over.

Thinking of these branes as sheets hanging on clotheslines, it’s easy to see how they could also wave or bump into one another. The collisions could, Greene suggests, cause localized Big Bangs within the branes, perhaps even periodic Big Bangs, allowing for cyclic universes that begin and end with a set time.

Of course, within each brane, you could have bubble universes and within the bubbles, patchwork universes. And while we’re going there, there’s no reason why there couldn’t be an infinite number of branes, each with everything going on inside it as mentioned above.

Let’s talk about something easier to wrap heads around – quantum physics.

14,000,605 is “Many”

Dr. Strange sifts through possible realities in Infinity War Marvel

In Avengers: Infinity War, Dr. Strange looked at all the possible outcomes of the coming conflict – all fourteen million six-hundred and five of them. When Tony asked in how many of those outcomes did they win…well, we all know that answer: just the one (which means that there are 14,000,604 really lousy alternate universes out there for the heroes of the Marvel Cinematic Universe…)

Strange’s head-blurring look at all of the possible futures is a visual representation of him sifting through all the many worlds of Everett’s Many Worlds Interpretation. And we only got six episodes of What If…? on Disney+… #cheated

Again, this is the central idea of Marvel’s multiverse idea – the stories we saw in What If…? happened because a different decision was made. If you think that each decision (again, not exactly a great interpretation of what’s going on with quantum physics, but this is all kind of useful as a model) has a counterpart (or counterparts) that forms its own reality, things get out of hand really fast. In the broader view of MWI, there may be an infinite number of alternate realities nearby us at all times…or just 10^500 according to some theories, which is still a lot. If you want to sound smart at parties, these alternate realities are believed to exist in what’s called Hilbert space.

A weird example that may connect to MWI can be seen in Thomson’s Double Slit Experiment where electrons shot at a target through two narrow slits will act either like a particle or a wave (they make different patterns on the target wall), depending, largely, on what you’re looking for. Look for electrons at the point where the electron should be passing through the slits, and you see electrons. Look at the target screen and you see a pattern created by wave interference. But if both outcomes are possible, who’s seeing the wave pattern when you’re seeing the electron?

Physics, man. Physics.

But before we get too far afield or start filling up Hilbert space, Marvel does have a mechanism to keep the multiverses from growing too wildly out of control – the Time Variance Authority (TVA) from Loki. As it appears, if a split in the timeline (a decision made that creates a new reality) starts to form a reality that is too…strong, or wile or otherwise needs to be pruned, because it doesn’t have the approval of He Who Remains, the TVA removes the source of variance, and the alternate line withers and returns to its main timeline.

The timeline got pretty corrupted in Loki, on Disney+ Marvel

And of course, there are no rules to say you can’t have a patchwork, bubble or brane setup within any or all of those alternate universes that split off from decisions that were made.

Slow Down, Multiversal Travelers

That last bit – that’s the crux of a lot of dissent about multiverses. Everything is possible. Nothing is fixed, therefore nothing can be measured. No test that can be performed. No conclusion to be drawn. This is the problem that Stephen Hawking and physicist Thomas Hertog had with the idea. Together their paper, “A Smooth Exit from Eternal Inflation” was published in Journal of High Energy Physics in 2018, shortly after Hawking’s death. In it, Hawking admitted he had never been a fan of the infinite multiverse concept because it couldn’t be scienced.

Infinite universes, each with its own set of physical laws and constants…there’s just no way to test it.

But that didn’t turn Hawking and Hertog off from the idea of multiverses. Blending gravitational wave theory, holography, and string theory, the two proposed a new theory for the multiverse that brought the possible number down from “infinite” to “manageable.” And in their view, “manageable” means possibly testable, perhaps by finding evidence of multiple Big Bangs via gravitational waves or other clues.

Benedict Cumberbatch, Rachel McAdams, and Xochitl Gomez in Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness. Marvel

That testable thing – that’s key. It’s something that Hawking, Hertog, Green and Tegmark all seek (or sought). The larger ideas of a multiverse – whichever flavor you pick – agree with at least one accepted theory of how the universe works. Those theories have been tested over and over. Other predictions based on those theories have proven to be true. If that’s the case, multiverse proponents say, then the predictions that these same theories may allow for the formation of universes other than ours must be taken seriously. As our tools and ideas get better, we can test more and look deeper.

After all, we used to think that there was no other land beyond our shore. We used to think that Earth was the center of the solar system. We used to think that our sun was the center of the galaxy. We used to think that our galaxy was the only one. We used to think that the universe was static and unchanging. Each of those “used tos” is missing its punchline: “until someone proved otherwise, and changed how we saw the universe.”

Portions of this article were adapted from “Multiverse Theory” in The Science of Rick and Morty, 2019, Simon and Schuster.