We love to tell ourselves about how our world may end, and for decades, it involved a lot of people.

The vision of the future given by 1973’s Soylent Green was dismal in many ways, but the scenes of people in the city packed shoulder-to-shoulder in every setting caught the existential worries of the era: Civilization would meet its end in part, because of overpopulation. The future was going to be hot and overcrowded. Until everything and everyone was gone.

But more and more demographers are coming to the conclusion that overpopulation isn’t in the cards for the earth.

Or rather, we’ll do our time with more people on the planet, but that time won’t last very long. Instead, things will head down a quieter, less dramatic road, but one just as significant: A decrease in fertility that will ultimately contribute to a population decline.

(c) Margaret Atwood

“The Plague of Infertility” is the named cause of the dystopian vision of Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale series, based on Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel of the same name. Both the novel and film versions of P.D. James’ The Children of Men offer the same: The fertility rate has dropped. Virtually no children are being born. Both stories strongly hint that humans might become an endangered species.

Things probably won’t end up quite that desperate for us, but a future with significantly fewer people on Earth is most likely our future.

“To keep the population stable, you need to have 2.1 children per woman,” says Dr. Stein Vollset, a professor of health metrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). “What we’re seeing almost everywhere is that the Total Fertility Rate is going down and has been for a long time.”

The population picture has a lot of moving parts, but two things are certain: population dynamics is more than just a math problem, and the world is going to change because of a decrease in fertility rates.

BUT FIRST, SOME NUMBERS

A short qualifier – while neither The Handmaid’s Tale nor Children of Men is explicit in its reasons for infertility, pollution and other environmental issues were hinted at as the causes in each world.

The decreases in fertility discussed here probably aren’t heavily influenced by plastic in the environment, forever chemicals in the air, food additives or even tight underwear. Probably. Some of those factors may play a role, but demographers, scientists who study the size and composition of populations as well as how they are likely to change, tend to look at the overall numbers, without assigning a fine-grained cause.

“The measures we’re talking about are the number of births per woman, per year,” says Dr. Allison Gemmil, a demographer at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. “We see many younger women in their twenties choosing not to have children like they used to in previous decades like the ‘80s and ‘90s, and an overall reduction in unintended pregnancies, but that’s what we’re looking at – just the number of births over time.”

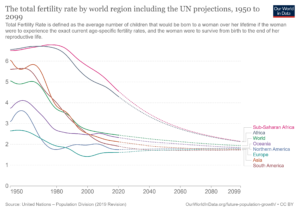

Total Fertility Rate is the average number of children a woman would have over her reproductive lifetime (15 – 49) if she had the same age-specific fertility rates as other women throughout that period. TFR is measured by adding the age-specific rates at a point in time, and changes over time, as well as geographically. For example, a fertility rate of 1.6 means that a woman in that region will have, on average, 1.6 children in her lifetime.

The replacement rate is the TFR needed to maintain population levels. Currently, the replacement rate is 2.1, meaning that to keep a population at its current levels, a woman needs to have 2.1 children during her reproductive life. The “0.1” is an artifact of the math, allowing for infant mortality within a population.

While it sounds counterintuitive, populations can grow with a TFR under the replacement rate. It’s like slowing a car to stop and putting it in reverse: It still moves forward, even though the speed is decreasing, but eventually, it stops and starts going backwards.

TFR is decreasing worldwide, on average, Vollset explains. He makes this claim in “Fertility, mortality, migration and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study” in The Lancet in June of 2020. Vollset is the lead author of a team of twenty-three researchers on the paper.

“If you go back to 1950, with the 195 countries we were looking at, only five were under the replacement level of 2.1,” Vollset says. “Looking at today, about half of the countries on Earth are below replacement.”

The Lancet paper breaks TFR down by country, showing values for 2017 and, if current trends continue, estimated TFR values for 2100. Globally, it shows the TFR to be at 2.4 in 2017, roughly half of 1950’s value of 4.7. Some highlights:

According to the study’s projections, Earth will see a peak population of 9.7 billion in 2064 (up from today’s 7.9 billion) before falling to 8.8 billion by 2100, and lower values as time goes on. This is due to 183 of 195 countries with predicted 2100 replacement rates of less than 2.1.

“Our fertility model is based on educational attainment in women and the met need for modern contraception, among other things” Vollset says. “And with this – and other – models, when countries’ fertility rates go down, they tend to stay low.”

Vollset’s model is just that – a model. There is controversy over the methodology and assumptions used for the IHME’s projections of TFR and population size in 2100 along with other assumptions. In August of last year, The Lancet published a letter signed by more than 150 demographers and population experts – including Gemmil – calling for a review of the study’s 2100 forecast and methodology.

Like many sciences dealing with people, demography is good at predicting in the short-term, say to 2050 or 2070, but further than that…say, 2100? That’s where the future gets hazy. That said, demographers agree that the TFR of most countries is falling, and that will have slow, but steady effects on the global population if it continues.

The UN Population Division’s (UNPD) most recent report shows a similar trend for TFR, with it falling to about 1.9 in 2100, and a peak population of 10.9 billion around the same time. Another analysis, from the Centre of Expertise on Population and Migration (CEPHAM) predicts a peak of 9.4 billion in 2070, falling to 9.0 billion in 2100. Post 2100, things get fuzzy and contentious between the various analyses. The IHME study predicts continued decline, the UNPD report has models that cover all possibilities, and there are some models that suggest we may see a population lower than it is now in 2100. Modeling populations 70+ years out gets a little imprecise, but again, the thing that virtually everyone agrees on is that TFR is decreasing. Again, like a slow river eroding rock to ultimately form a canyon, that will have larger, dramatic effects.

Total fertility rate of the world, by region. From “Our World in Data” Licensed under CC

WASN’T THIS JUST THE PANDEMIC?

The decrease in fertility rate publicized in 2020 is not due to COVID-19. “Even before the pandemic, we’ve been seeing this continued drop in fertility,” Gemmil says. “The steep decline we’re seeing now has been going on since the Great Recession in 2007.”

The effects of the pandemic – which accelerated the decline in fertility rates – are visible in the data for 2020 however. 2020 has the lowest recorded number of births in the United States since 1979: 3,607,201 – a 19% decrease since 2007. The United States population grew in 2020, but by 0.48% – smallest increase seen in half a century, and that was further reduced to 0.1% in 2021 as mentioned earlier.

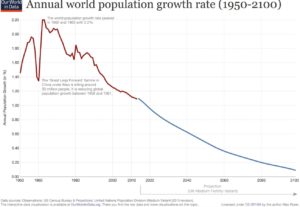

For a more global perspective, the world’s population growth peaked at 2.1% growth per year in 1968 and currently stands at 1.1%.

“At least half the states in the U.S. had more people die than be born in 2020,” says Kenneth Johnson, a demographer at the University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy. “It’s a case where COVID exacerbated what we’ve been seeing – there were more deaths, and it appears that COVID has depressed the birth rate.”

The numbers were exactly the opposite of what was suggested in the early days of lockdowns – a possible pandemic baby boom. “They could have just asked us,” Gemmil says with a chuckle. “No demographer would have said we were going to see a baby boom. A pandemic does not provide ‘baby boom’ conditions.”

Data backs up Gemmil’s point – lockdown babies would have started showing up in November or December 2020, but no surge in births was reported. In fact, the number of births at the end of 2020 showed the sharpest decline of the year. Pandemics and uncertainty about the future isn’t conducive to making babies.

AND IN THE LATEST NEWS FROM THE POPULATION FRONT…

In mid-January, China’s National Bureau of Statistics announced its latest population data, stating that its birthrate declined for a fifth straight year. 2020 saw 12 million births in China, while 2021 saw 10.6 million. Also in 2021, China reported 10.1 million deaths.

The decline in births being seen in China is certainly partly due to the nation’s “one child” policy echoing through time. While the main goal of the policy was to curb China’s runaway population growth of the 1960s and 70s, the restrictive rules on families resulted in many sociological and cultural changes, as well as fewer girls being born while it was in effect, from 1980 – 2015. Seeing the demographic effects that were coming, China began allowing couples to have two children in 2016, and relaxed that rule to three in 2021. But still, it’s estimated that there are three million fewer women of childbearing age in China as a result of the policies.

The New York Times quotes He Yafu, a demographer in Zhanjiang as saying that the difference between births and deaths in China in 2021 effectively is in the range of zero population growth, and the trend of zero growth is something, he says, “cannot be reversed.”

Also, in late 2021, South Korea announced that its death rate surpassed the nation’s birth rate for the first time. The country’s total population started dropping last year as well, eight years earlier than the government had predicted, in 2019.

Rounding out major Asian population centers, India reported that its TFR had dropped to 2.0, compared to 2.2 five years earlier, when the last National Family Health Survey was taken. The news of a slowing growth rate in India was seen by public health experts in India as good news overall, however, it also noted a sharp divide between rural and urban TFR. The fertility rate in more southern, urbanized population centers is 1.6, while in the rural areas such as the Bihar state, the fertility rate hovers around 3.

WHY THE FERTILITY SLIDE?

To piece together why the United States and the rest of the world are seeing a decrease in fertility rates – demographers look at things other than just numbers.

The chief reason behind the worldwide decline in TFR, according to Vollset, is increased education, opportunity, and access to contraception for women. When women attain more power and agency than they’ve traditionally had in family planning, they use it.

World Population Growth Rate from “our World in Data” licensed under CC

Also, both worldwide and in the United States, urbanization plays a major role – as people move from the rural areas to cities, fewer hands are needed for work, and raising a large family is more expensive than in the country.

“There are concerns about the environment, achieving your own personal fulfillment, the financial considerations of raising a child, or concerns about healthcare in the future,” Johnson says. “That’s why demography is so intertwined with sociology and psychology and economics. All of these different forces come into play in the decision to have children.”

HAVING BABIES LATER, DRIVING THE DATA?

What appears to be affecting TFR the most in industrialized nations is the shift in the age of women having children. Data from the United States shows there are fewer teenagers and women in their early twenties having babies than ever before. Delaying having children, Gemmil says, is what demographers saw in Europe over the past three decades.

“We call it a postponement transition,” Gemmil says. “The United States is starting to move into it, while countries in Europe are well on their way into it. Once it’s underway, it’s probably going to be underway for a while, and will continue to bring fertility rates down.”

Postponement used to be something that was seen mostly among women of higher socioeconomic status, but now it’s seen among all ages, races, and ethnicities. It’s become more of a social norm to wait to have children, according to Gemmil.

However, Gemmil adds that there’s not a large amount of evidence that women who put off having kids until a later age end up having them or having as many children as they planned. As before, the reasons are numerous: finding financial stability along with an establishment of a lifestyle or a career that would make having a child difficult along with the fact that as women get older, pregnancy and childbirth can become more difficult and riskier.

In Johnson’s estimation, there are approximately 3 million women in the United States right now who are in their prime childbearing years, who’ve postponed having children. If they made choices the way women had prior to 2007, they would be mothers. By his estimation, that’s approximately 7 million fewer babies born.

This pattern isn’t entirely new. Studies are showing that there appears to be a correlation between earlier-in-life childlessness and later-in-life childlessness.

“Women who were in their twenties in the Great Depression had the lowest fertility of any group of American women, 20% of them never having children,” Johnson says. “And we see that in other recessions, including what we saw in 2007.

“If the women now follow that pattern, a lot of the babies aren’t going to show up at all.”

ON THE IMPORTANCE OF IMMIGRANTS …

Historically, falling fertility rates in a country have had a reliable backstop: immigrants. Typically, newcomers have a higher fertility rate than natives in the destination country and help keep the population growth moving forward.

Historically, falling fertility rates in a country have had a reliable backstop: immigrants. Typically, newcomers have a higher fertility rate than natives in the destination country and help keep the population growth moving forward.

But that’s not happening as much as it used to.

“On the whole, the fertility rates of immigrant populations have been diminishing as well,” Johnson says. “Of course, we have less immigration into the United States now than we’ve had in the past, so that plays a role, but at the same time, the decreased fertility is also showing an effect.”

As reported earlier this year, while 2021 saw the slowest population growth in its history, 0.1%, the majority of the growth that was seen (even at its sharply reduced levels) was due to immigration.

As time goes on and more countries feel the demographic shifts of sub-replacement rate fertility, countries that had a…less than welcoming attitude towards immigrants will be faced with a stark choice. As a population ages and becomes demographically “top-heavy” with more olds than young, workers and caregivers will become scarce. Vollset suggests that countries with fertility rates above replacement will likely become the source of immigrants for many countries in years to come – think the Sojourners of Children of Men. Nigeria, for example, is a country that’s predicted to lead Sub-Saharan Africa in keeping TFR high and above replacement for the remainder of the century. Demographically, it’s estimated that two-thirds of the world population growth through the middle of the century will happen in Africa.

But looking at the long-game, that’s a short-term fix, as ultimately, the populations of countries that were once sources of immigrants will themselves likely fall below replacement.

IS THERE A TURNAROUND?

Getting a fertility rate back up to 2.1 is a challenge. That is, if it’s something that can be done at all.

“Many countries in Europe have much more robust social services systems than the United States – many countries offer free preschool, financial assistance and other incentives to have more children,” Johnson says. “Even when incentive programs were offered on top of what they traditionally offer their populations, their birth rates only went up slightly. None of them jumped above two, and they came back down when the programs ended.”

Changing the fertility rate is a matter of decades or longer, not years. The current slide will continue, according to not only Vollset, but the UN report and other models of population dynamics, through the end of the century and beyond. Policy and incentives can be offered by forward-looking governments, but again, this isn’t just math.

You can’t ask for a better example of this than to look at China. Though the one-child policy ended in 2016, and starting last year, families can have up to three children, any upward blip in the nation’s population growth is…inscrutable at best.

And also, people have children when they feel good about the future.

“In a way, fertility is related to the mood of society,” Vollset says. “After the second world war, there was a lot of optimism, other elements lined up just right, and we had a baby boom. I don’t think there’s that sense of optimism today. I come from Norway, and every year in the New Year’s address, the prime minister asks couples to make babies. Not many people seem to be listening.”

Loups=Garous anime cover, based on the novel by Natsuhiko Kyogoku, (c) sentai filmworks

Some countries have already begun to adapt to the changes, or, if not adapt specifically, have started to process the changes, as evidenced through their fiction. Both Japan and China have seen their own demographic changes, with more to come on the horizon, and they’re explored in stories such as Loups-Garous by Natsuhiko Kyogoku, The Stories of Ibis by Hiroshi Yamamato, and “Tongtong’s Summer,” by Xia Jia. Each is set in worlds where there are far, far humans on the planet then there are now.

WHAT’S THIS GOING TO DO TO THE WORLD?

All of this can paint a mixed picture for the future. A shrinking population will change things. A lot. Not all of it good, not all of it bad.

While we’re decades from a noticeably shrinking population, a drop in fertility rates is always a sign that Things Are Bad, such as in The Handmaid’s Tale, and Children of Men, where the decline in fertility had destabilizing effects on society. That’s just a lack of planning, right there.

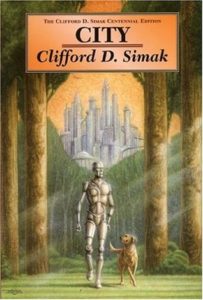

Once Earth hits peak population, the numbers will start to fall and probably pass current world population levels while continuing downhill. While some projections can lean toward an empty earth, such as that seen in Clifford Simak’s City where sentient dogs struggle to remember what “man” was, a demographically driven, self-extinction event is not the end of our story on this planet.

“I’m certain the population won’t go down to zero,” Vollset says. “But then the question is, where will the global population land? Where should it land? Those will be important questions. From a sustainability perspective of the planet and in terms of climate change, and carbon emissions, maybe it’s not a bad thing that the population will decrease.”

While a population growing at a slower rate and then shrinking is good when viewed through some lenses, it presents demographically-based challenges. Nations that depend upon a large working population to help support, at least in part, an older population through social programs will be forced to readjust as the working population shrinks.

Fewer workers also mean reduced tax income for the government, as well as increasing health care costs and fewer workers to care for an aging population.

According to Geeta Nargund, director of CREATE Fertility at St. George’s Hospital, the forthcoming demographic changes caused by declining fertility rates will require a radical rethink of public health, work-life balances, economic stability, education, immigration and other similar issues for every country.

Proposed policies to address declining birth rates in developed countries, suggested by Nargund

Entire economies and economic structures must be re-thought to prepare for the coming changes, or perhaps worse, react to them. Blended into the mix are questions of culture, society and national identity, as historic population subsets start to shrink, others grow, and immigrants are welcomed as a workforce.

In terms of the United States, this shift will be happening sooner, rather than later. According to the United States Census Bureau, by 2030, there will be more adults 65 and older than children 18 and under for the first time in the history of the country. The U.S. will also see immigration become the primary driver of population growth that same year due to falling fertility rates and more deaths among the aging population. That shift will bring about major demographic changes in the country, making the U.S. more pluralistic, and by 2045, non-Hispanic Whites will no longer make up the majority of the population. That last part alone carries many loaded questions about who should, and who will sit at the seats of historic power in the country’s leadership. The same question can be asked about the world as the population centers shift, and until-then underrepresented populations ask for seats at the table as well.

City, by Clifford Simak – a future where sentient dogs struggle to remember what “man” was…

When it comes to working to push the numbers back up to replacement, things start to move into the “just because you (think you) can, does that mean you should?” camp.

After all, much of what brought us to this point, was better access to education and birth control for women around the world. And of course, global population decline helps to lessen the strain on natural resources. Signs of progress. Author Kim Stanley Robinson squarely set his The Ministry for the Future in a world churning through a demographic (as well as other) transition, and showed while the journey may be difficult, a drop on global fertility isn’t a one-way ticket to The Handmaid’s Tale or Children of Men if we don’t want it to be.

“I’m not totally on the side that thinks the world’s population will shrink to a really small number,” Gemmil says. “I don’t think having fewer people on the Earth in the future is necessarily a bad thing. But it will cause changes, and some might be difficult, but overall, less humans on earth in the future might not be the worst thing for the world.”

All charts in this article can be found at Our World in Data: World Population Growth