Superboy’s origin story is as convoluted as it gets in comics. Jon Kent is the biological son of Clark and Lois, originally conceived and born in reality that doesn’t exist anymore. That story retconned so he was conceived and born in the current DC Universe(*). Jon lived life as a 10-ish year old for a few years, went to space with his resurrected grandfather, was captured in a parallel universe and held there for seven years. He finally escaped and came back to his home universe where only weeks had passed. Now 17-ish, Jon went to the 31st century as a member of the Legion of Super-Heroes. He had adventures and learned things, and came back to the present. Most recently, he’s stepped into his father’s role as “Superman” while his dad trips off into space, perhaps never to return.

Basic comic book stuff. But that’s not what we’re talking about right now.

Superboy’s powers are . . . something else (okay, okay – he’s Superman in-continuity right now, but since we’re talking about his genetics, we need to keep him apart from his dad, so for the purposes of this article, Superboy is Jon, Superman is Clark. Cool?).

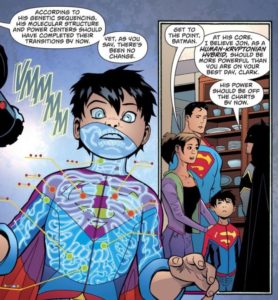

Despite the costume, the strength, and the flight, he’s not a mirror copy of his dad. There’s a hint that Jon is . . . more. As much was said by Batman in Superman #20.

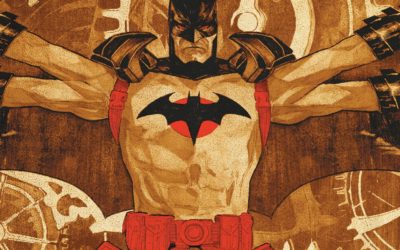

If Batman said it, it has to be true. From Superman #20, (c) DC Comics

Batman’s observations have carried through to the present day – foreshadowing that Jon is going to be more than his father. Somehow, Jon’s human-Kryptonian genetic blend is superior to his dad’s 100% Kryptonian genetics.

The word Batman was hunting for up there was heterosis.

Biology Class: A Quick Refresher

Just so we’re speaking the same language, let’s remember that class with the cells and the DNA from a little while back:

gene: a sequence of DNA that is responsible for a function or appearance of an organism. Genes are the unit of heredity – they’re what get passed from parent to child. A gene is part of a chromosome.

allele: a version of a gene, most often explained as “dominant” or “recessive” (though there can be more than two versions). Generally, each parent gives one version of the allele, and the offspring has two copies. The different versions come about through mutation.

homozygous: referring to having two copies of the same allele, either two dominant, or two recessive.

heterozygous: having two different copies of the allele, in the simplest sense, one dominant, one recessive. Most often heterozygous offspring will display the characteristics of the dominant allele.

genotype: the genetic makeup, or collection of genes.

phenotype: the observable characteristics of an organism, as determined by the genotype.

Making Hybrids

Let’s get something out of the way from the start – normally, members of two different species cannot produce offspring. Kryptonians and humans (as if it’s not clear) are not the same species. Maybe related somehow, but not the same.

But sometimes, it works. Two related, but different species do have offspring – hybrids.

To create hybrids between two species, they must have overlapping territory, similar morphology, similar mating behaviors and mechanics, similar times of fertility, and similar physiology.

For example, when a female horse really likes a male donkey, they can produce a mule. There are ligers (male lion, female tiger). Zebroids (a zebra mixed with any other equine) exist. Beefalo are real (a buffalo/cow hybrid). Virtually all humans, aside from those living in sub-Saharan Africa carry somewhere between 1 and 4% Neanderthal DNA. The list goes on and on.

Don’t hate on the zonkey. You’re most likely a descendant of a hybrid, too

Research suggests that around 10% of animal species and roughly 25% of plant species hybridize with at least one other species. A human-Krytponian hybrid? Not the weirdest thing ever.

While we’re talking about interspecies hybrids, let’s talk about fertility and sterility.

In many cases, hybrids are sterile. The problem with reproductive viability among hybrids comes down to the number of chromosomes. If the parents don’t have the same number of chromosomes in their reproductive cells (eggs and sperm), the hybrid offspring ends up with an odd number in their cells. For example, a female horse has sixty-four chromosomes (thirty-two in an egg cell) while a male donkey has sixty-two (thirty-one in a sperm cell). The resultant mule has sixty-three – an odd number that cannot be split evenly in reproductive cells. Add that to differences in chromosome structure, and you’ve got large (but not total) barriers to hybrid reproduction.

Not all interspecies hybrids are sterile. Coydogs (a coyote-dog hybrid) are always fertile and can make more coydogs. Ligers have been known to be fertile. Beefalo are fertile (which could be a classification issue, rather than a real hybrid thing going on). But fertility of interspecies hybrids does exist, and in most cases, the male hybrid is reproductively viable, while the female is more likely to be sterile.

Into the DC Universe weeds for a minute…the fact that Krytponians and humans are similar enough to produce hybrid offspring can walk down some interesting streets about interstellar colonization of the DCU which can also suggest explanations for the abundance of humanoid aliens. And further into the weeds, for those of us who still stan Nightwing and Starfire as a couple, their Kingdom Come-reality daughter, Nightstar…yup. Keep that torch burning.

Dick and Kory are gonna get back together, and Nightstar will be their daughter…I know it!

Making Super2 Man: Heterosis

What’s being hinted at with Jon – a hybrid between a human and Kryptonian is “better” than a “pure” Kryptonian – goes by a couple of names: hybrid vigor or heterosis – and sometimes outbreeding enhancement. Let’s go with heterosis.

Heterosis is the name given to the improved function of any biological quality in hybrid offspring resulting from the union of two individuals of the same species (different breeds or varieties), individuals that are geographically isolated, or species that are closely related. The more heterozygous genotype appears to increase the likelihood of a beneficial phenotype.

As plant geneticist G.H. Shull explained in 1948: “The physiological vigor of an organism as manifested in its rapidity of growth, its height and general robustness, is positively correlated with the degree of dissimilarity in te gametes by whose union the organism was formed … The more numerous the differences between the uniting gametes — at least within certain limits — the greater on the whole is the amount of stimulation.”

In plants, this can increase crop yields (seen in field corn/maize, onions, spinach, sugar beets, rice, and cannabis), tolerance to adverse conditions and overall vigor; while in animals, it can increase working ability (mules), meat production (cows and pigs), or overall robustness and otherwise desirable traits (healthier, more manageable livestock).

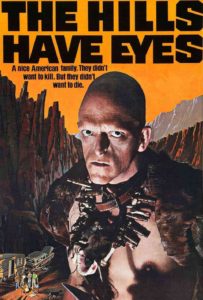

Heterosis is at one end of the line that has inbreeding depression at the other. Inbreeding often results in unfavorable genes concentrating in offspring, as related individuals (with similar genotypes) breed. Reduced genetic mixing often has not great results.

The Hills Have Eyes (1976) – the ‘70s and ‘80s horrors movies had a weird fascination on inbred families

And just to be totally clear – heterosis is not the “modification” of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The end result (a more robust corn plant, for instance) may seem the same as the end goal of GMOs, but heterosis is either naturally occurring or facilitated by conditions or, in many cases, humans.

Seeing heterosis in an organism is one thing. Explaining how it works is something that’s still up for grabs. Generally, it comes down to two broad ideas:

- Dominance: The effects of detrimental versions of genes are reduced or removed by dominant alleles, resulting in a heterozygous hybrid with more vigor. This would be seen with the introduction of an individual with a unique genetic makeup to a population that has inbreeding depression.

- Overdominance: With some genes (or combination thereof), the heterozygous (different) mix is the better, or optimum genetic state for the offspring. In this theory, the mix of genes is even better than the homozygous state for an individual, even one receiving two copies of the favorable version of the gene.

From those general explanations, a lot of uncertainty is left on the table. The specific why and how heterosis works is still up in the air.

Some pointers and ideas –

- The degree of heterosis (the superiority of the hybrid compared to the parents) appears to depend upon the genetic distance between the parents. This has been seen in many species, both plant and animal, perhaps in humans. A study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in 2011 suggests that the geographical distance between the places where a child’s parents were born has a proportionate effect on the height of the children. The farther apart the parents’ birthplaces, the taller the offspring. Or, at least, the greater difference played a role – socioeconomic status, height of the parents and distance all played significant roles in the height of the offspring.

- The combination in the novel mix of genes may result in the hybrid having a reduced metabolic energy cost. One such theory suggests that organisms demonstrating heterosis use less energy at rest than non-hybrids, allowing for the energy and resources to be used for different systems and development.

- When individuals from two closely-related species reproduce, the “genetic noise” that can be caused by a large variation between genes in same-species matches, can be reduced. As a result, the hybrid shows less variation, and more vigor.

- The heterosis seen in a hybrid may be the result of epistasis – certain genes (that aren’t alleles to those in question) have interactions with others, resulting in their enhancement.

The wide field of possible causes, as well as finer-grain suggestions on how heterosis works and what causes it has led some researchers to discount the idea that a simple, universal explanation for the phenomenon will ever be discovered. There are just too many variables, too many possible players when it comes to genetics, and too many conditions in which a hybrid is raised to put a lock on a specific cause, or collection of causes.

Sometimes the resulting phenotypes of hybrids are favorable, sometimes, they’re not. But heterosis is a thing. It does happen. Breaking down the mechanisms? We’re nowhere close to figuring that out, consistently. The origin of many hybrid species of plants and animals can easily be explained as “happy accidents.”

The Big Picture for Superboy?

It’s comics, who knows? He loses his powers tomorrow, or whenever Superman comes back from space. A new editorial regime decides Jon needs to go. But editorial and market-based winds of fate aside, a Kryptonian/human hybrid on earth raises interesting possibilities:

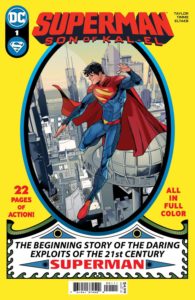

Superman, Son of Kal-El #1 – Jon strikes a familiar pose, art by John Timms, (c) DC Comics

- As mentioned earlier, the fact that Clark and Lois had a child suggests some degree of relation between Homo sapiens and Homo…er, sapiens kryptonesis. At surface value, Jon is a normal humanoid, resembling a human being. So’s Clark. There’s some shared biology between humans and Kryptonians there. And the chances of evolution happening the same way, twice so close together? Krypton was only 27.1 light-years from earth, after all. That’s next to impossible. Hey DC Comics – how did that happen?

- Future DC – if: (a) Jon is fertile (there’s a good chance that he is, given he’s male and appears to demonstrate heterosis), and (b) does one day have kids…if overdominance is the way to go in this case of heterosis, some of those kids (and possibly their kids) will be Supersomethings. Jon’s genes could be a “refresher” for the human race, over time, making it more fit.

- Clark and Lois have more kids. Remember – chronologically, Jon is only about ten years old. If storylines or corporate overlords demand it, there may be another hybrid. Will it grow to one day be better than Superman, following down the road Jon is on? Maybe. Heterosis isn’t guaranteed with hybrids. While it worked with Jon, it may not work with another child. See Superman and Lois on The CW for more about how that works out.

- Other alien-earth hero hybrids. Yes, I’m going back to Dick and Kory. We’ve seen any number of stories set in the future with kids of alien/human parents, and ultimately…that’s scientifically plausible. It’s more plausible if we find something out about how all the humanoid “alien” races of the DCU all arose from human stock millions of years ago, but we can leave that ball in DC’s court.

- Super-Superman? Rather than suggesting that Jon’s enhanced powers are due to a lack of control on his part, DC seems to be all-in on the idea that Jon is … more than his dad. And yeah, that’s cool. But if time has taught Superman fans anything, kewl new powers for Superman just aren’t the thing to do. Let’s just settle on (it’s also what comic book science would support) the notion that Jon is faster, stronger, tougher and has better heat vision and freeze breath than his old man – that’s for his powers. What really makes him better? Having grown up with Superman as a dad and Lois Lane as a mom. Jon’s the embodiment of what all parents hope for their kids, heterosis or not.

(*) – in Jon’s origin story. His origin, origin story, Clark’s powers were suppressed when Jon was conceived, it’s dark in a womb, and then he was delivered with the help of Wonder Woman. This detail allowed DC to dodge years of questions from fans at comic con panels asking about Larry Niven’s “Man of Steel, Woman of Kleenex” essay from 1969. Thank you, DC editorial. His new one is a little less…clear, but Niven’s points have been left, thankfully, unaddressed.