In Wonder Woman, Dr. Poison has everything going for her as a classic villain. She’s broken. She’s creepy. She’s troubled. She’s brilliant. And she knows her science.

Apparently in the thrall of General Ludendorff, Dr. Poison – Isabel Maru, played by Elena Anaya – was responsible for developing, well…poison weapons for the Germany army in World War I, including a hydrogen-based gas (small molecular sized particles could slip through filters) that could penetrate gas masks (and crack their glass too).

As for where the character came from, Dr. Poison was Wonder Woman’s first “costumed” villain, appearing in 1942’s Sensation Comics #2 (get both #2 and #3 at Comixology here). In that appearance, Dr. Poison was revealed to be Princess Maru, an Asian Princess tied in to both the Yellow Peril and the rising anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States at the time. Since her first appearance, Dr. Poison has been rebooted three additional times in DC Comics, and is currently Marina Maru, leading of an organization called…Poison (no, not the ‘80s hair band).

Dr. Poison in the film is frightening enough, but in this case, there’s a real-world analogue, someone who has been celebrated and castigated through the years. Our world’s own complex character using science to help and hurt – Fritz Haber, the “Father of Chemical Weapons.”

Okay, but before we get into it, was Haber really the inspiration for the original Dr. Poison in 1942?

Sensation Comics was originally written by William Moulton Marston who created up Wonder Woman and her initial cast, including Dr. Poison in issue #2. While there is no direct evidence connecting Dr. Poison with Haber, Marston was alive when chemical weapons made their debut. The Wonder Woman creator was at Harvard during World War I, and would’ve heard of the use of chemical weapons by the Germans following their first use in the Second Battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915. The use of the gas was reported widely, making papers throughout America, from The New York Times to The Chicago Tribune.

Firsthand accounts of the gas were stuff of nightmare – a sickly looking yellow-green gas rolling across the landscape turning any vegetation brown and wilted, flowing down into depressions and pits in the ground, ultimately drifting down into the trenches where the Allied soldiers waited. So does Haber equal Dr. Poison? Maybe not directly, but if you were writing about a “mad scientist” who was behind chemical weapons in the ‘40s? Haber was somewhere in your head, influencing the creation.

If you can remember him from a chemistry class or a YouTube video, you may already have a sense for who Haber is. But if we’re being honest, Haber, like Wonder Woman’s Dr. Poison, is a complex individual that resists the broad-brushing of turning him into a simple villain.

Fritz Haber is often cast as a lone, German mad scientist in stories about chemical weapons used in World War I, but that’s not quite accurate. Chemistry was the hot science in the early 20th century and in many ways, World War I was a chance for the leading industrial nations to show off their technologies to the rest of the world. Despite The Hague Convention of 1899 and 1907 which prohibited the use of asphyxiating gas projectiles in war, France used a version of tear gas on the Germans in 1914, and once the Germans introduced gases on the battlefield, the Allies’ answered with gases of their own. Lost to most history and chemistry texts, in fact, is the rivalry Haber had with the French chemist Victor Grignard who also studied gas weapons. No, this wasn’t a case of Haber secretly toiling and developing chemical weapons for war. The whole world was headed in that direction. Haber just got there first.

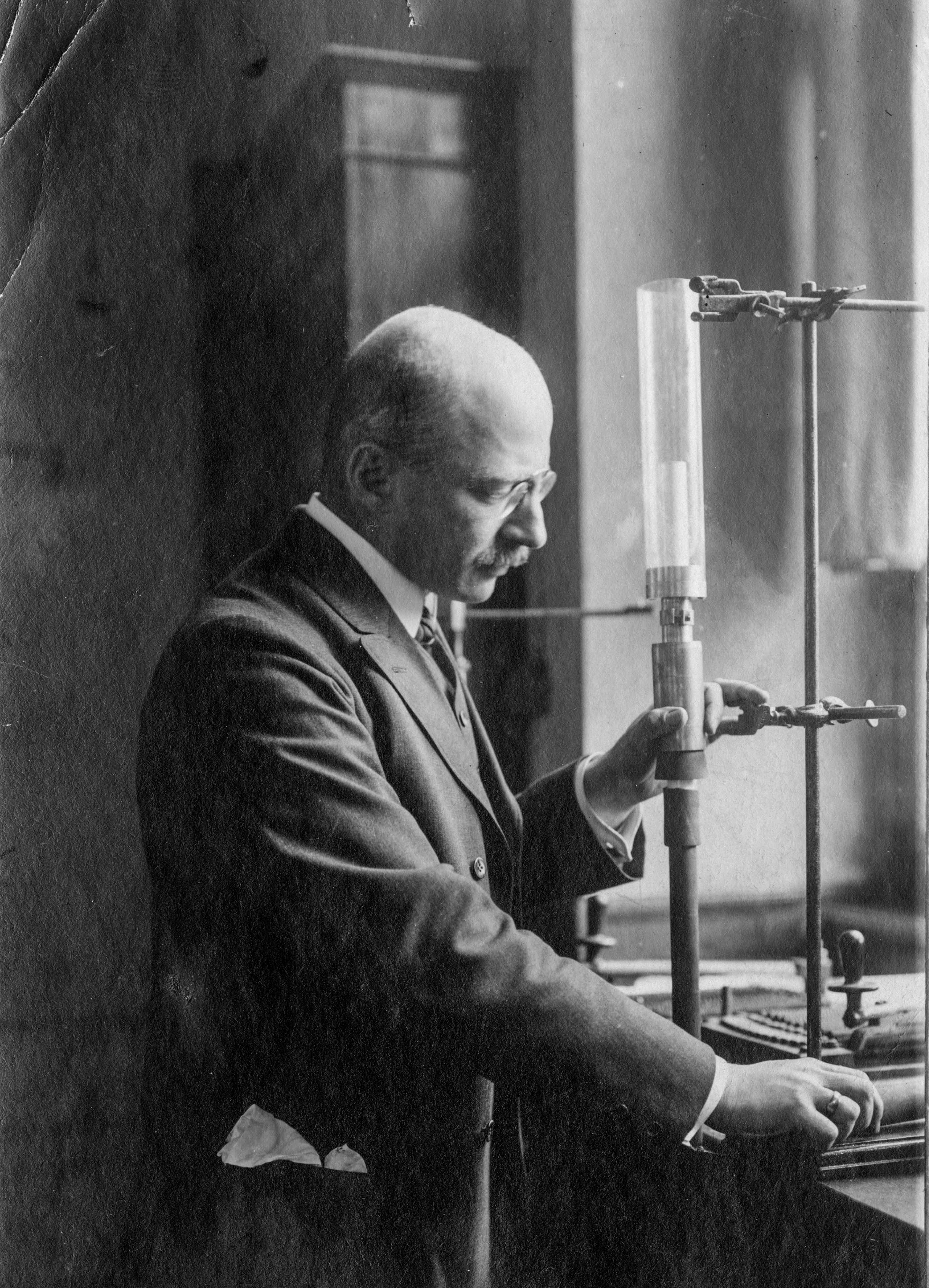

But before we expose his dark side, let’s make one thing clear – Haber was a brilliant chemist. Before he became known for his work with chemical agents Haber, in collaboration with Carl Bosch invented the Haber-Bosch process, a means to literally pull nitrogen out of the air (with the use of a metal catalyst under high temperatures and pressures)

Chemistry students know the Haber-Bosch equation well – it’s usually the go-to equation to explain Le Chatelier’s Principle:

N2 + H2 -> 2NH3

The ammonia (NH3) is then used to produce fertilizer which, in Haber’s time was desperately needed to help feed the world’s rapidly growing population. The process is still used today, and is often pointed to as one of the main factors that has allowed the earth’s population to grow to over 7 billion. For their work on the process that is a benefit to all mankind, Haber and Bosch were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1918 and 1931, respectively. Haber’s win in 1918 was…controversial to say the least.

However – all that nitrogen coming from the air attracted the attention of the German Army which needed the element for nitrogen-based explosives during the Great War.

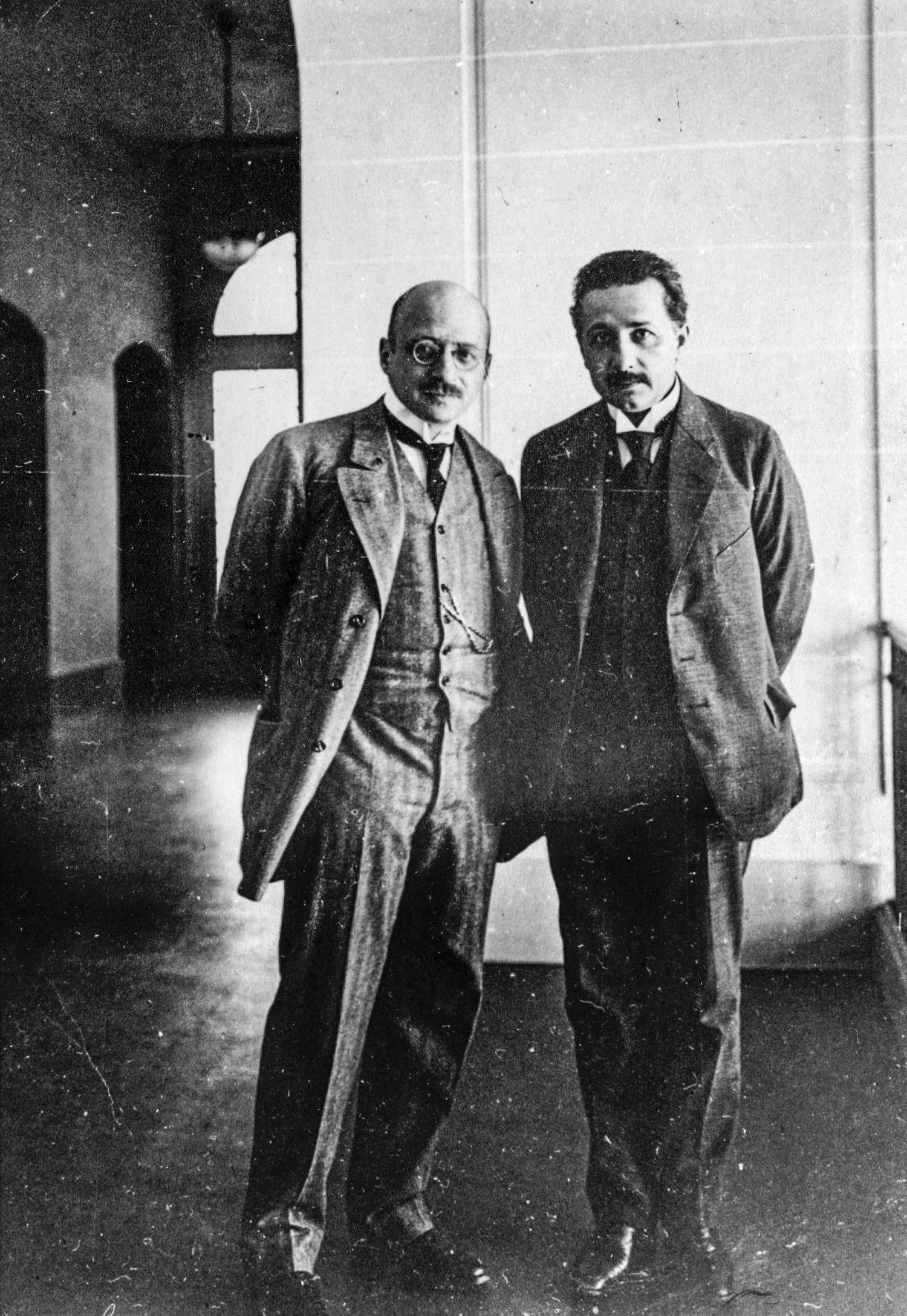

When the Great War came, Haber saw himself as a German first and a chemist second (in opposition to his friend, Albert Einstein, who was critical of Germany), and told the Germany government he would do whatever his country needed to help in the war effort.

Credit: Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berlin

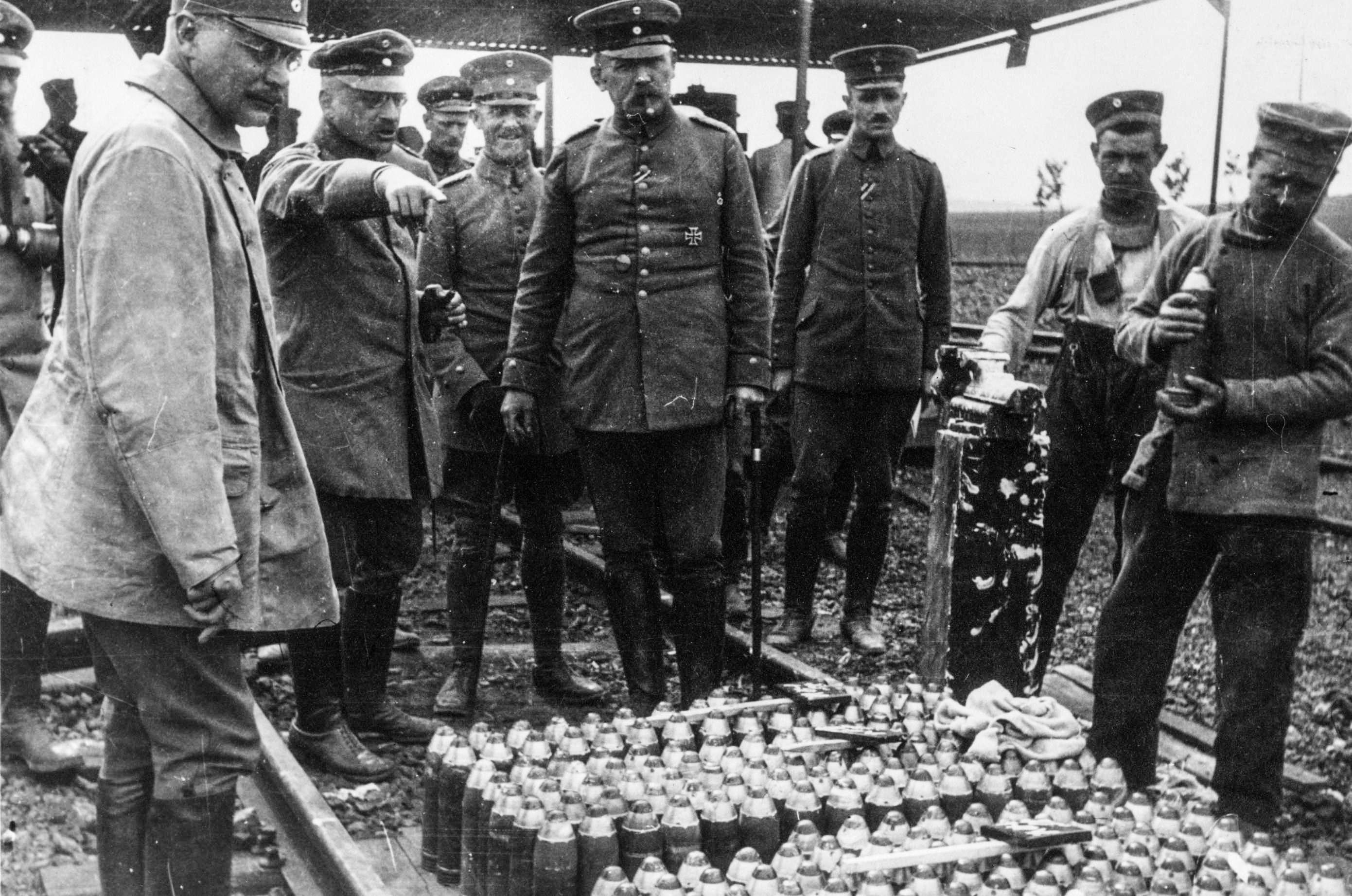

Haber (pointing), instructing soldiers on the use of chlorine gas – in the canisters on the ground

Like Dr. Poison, Haber was not seen as a traditional war hero by the leadership of the German military. These were generals and soldiers of the Victorian Era – gentlemen first, soldiers second. Haber’s ideas of killing the enemy with gas were seen as “unchivalrous” and “repulsive.” But Haber was steadfast, insisting that the gas would be a way to decrease the number of German casualties (while increasing those of the Allies) and end the war faster (with Germany on top). In the end, Haber’s plans for chlorine gas were a means to an end, and the generals finally took Haber’s advice of “using chemical warfare with conviction.”

With the military finally behind him, Haber threw himself and his lab at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry into the business of making a poison gas for the troops. By April of 1915, Haber had his perfect concoction and was on the front at Ypres in Belgium. There he waited for weeks until the winds were just right, and on April 22nd at sunrise, released over 168 tons of the gas from canisters (keeping with the spirit of The Hague Convention which outlawed gas projectiles).

Denser than air, the gas drifted like a low, yellow wall towards the French trenches. Hundreds to thousands (depending upon your source) of French and Algerian soldiers died from exposure. While the gas use did not lead to an immediate victory for the Germans, it emboldened Haber and the German High Command to view gas weapons in a favorable light.

Haber oversaw another attack at Ypres, this time on Canadian troops, and by May 2nd, had been promoted to a uniform-wearing captain and was headed home to Berlin for a party in his honor. He was living a celebrated existence at this point – a party on the 2nd, and then on May 3rd, he was headed to the Eastern front to oversee a gas attack on the Russians. Haber’s wife, Clara Immerwahr (a brilliant chemist in her own right) long disagreed with her husband’s perversion of science to develop chemical weapons and on the night of the party, shot herself in the chest with his service revolver (she didn’t die immediately and was found by their 12 year old son, Hermann, but Fritz slept through the shooting). Haber was so broken up by his wife’s death that he didn’t bother changing his plans and headed out to the Eastern Front the next day – though he later admitted he was still haunted by Clara’s face and words.

After the debut of Haber’s chlorine gas, the chemist went on to oversee the development of phosgene gas (COCl2) and mustard gas ((ClCH2CH2)2S). Each of the three gases used in World War I are horrible, and while both German and Allied armies rapidly developed gas mask technology to minimize the effects of the gases, over a million people died from poison gases in World War I between their debut at Ypres in 1915 and the end of the war in November of 1918.

Strictly from the chlorine gas side of things, inhalation of the gas is a horrible way to go, thanks to the reaction that happens in the lungs:

2Cl2 + 2H2O -> 4HCl + O2

Recalling chemistry – HCl is hydrochloric acid. The water on the reactant (left) side would be found in the lungs or on the surface of the eyes. Those without protection could be blinded by the gas, while in the lungs, the alveoli would be damaged or scarred, reducing the ability to absorb oxygen – if you were lucky. If you were unlucky, when exposed to hydrochloric acid, cells in the lungs would rupture (lyse), releasing their cellular fluid. Fluid-filled lungs would literally lead to drowning on dry land.

On April 26th, 1915, The New York Times reported of the battle:

“Some (soldiers) got away in time, but many, alas, not understanding the new danger were not so fortunate and were overcome by the fumes and died poisoned. Among those who escaped, nearly all cough and spit blood, the chlorine attacking the mucous membrane. The dead were turned black at once … (The Germans) made no prisoners. Whenever they saw a soldier whom the fumes had not quite killed they snatched away his rifle … and advised him to lie down to die better.”

Mustard gas and phosgene were, reportedly, even worse, sometimes delaying their deadly effects until after the battle was over. Haber also worked on a gas blend called maskenbrecher or “mask breaker” – an agent that would be small enough to get through the filters of a gas mask and cause a violent reaction from sneezing to vomiting, forcing soldiers to remove their gas masks, and then be exposed to the deadlier gases from which their masks were protecting them. Hey – what was that gas Dr. Poison was working on again?

Following World War I, Haber was named a war criminal by the Allies, but like Dr. Poison in Wonder Woman, he was able to escape capture and prosecution. Haber fled to Switzerland in 1919. His name was later removed from the list, and he returned to postwar Germany a hero. During these postwar years, Haber continued his research into poisonous gases, in direct opposition to the Treaty of Versailles. Part of the research into position gases led to the development of a pesticide, Zyklon A in the 1920s. Another Haber project in the years of reparations being paid by Germany – he proposed that he could extract gold from seawater. Ultimately, his plans bore no fruit.

While he was initially seen as a favored son in his beloved Germany, the postwar years became difficult for Haber as the National Socialist Party rose to power, and Haber’s Jewish lineage was brought to light (despite his conversion to Christianity years earlier), effectively ending his scientific career. Doors that were once thrown wide for him were firmly closed. Haber fled his beloved Germany for England, but his work with chemical weapons kept him from finding a home there. Haber wandered Europe for some time, ultimately dying of a heart attack in a Swiss hotel.

In a cruel twist of fate, or what some may see as karma, Haber had one final role to play. His Zyklon A was reformulated by the Nazis – they didn’t like the gas’ odor – and renamed Zyklon B. The gas was used on Jews, most likely including some of Haber’s relatives, during World War II.

A complex man during his lifetime, Haber’s legacy is equally complex. Some estimates suggest that half the world’s population would not be here if not for the Haber-Bosch process which allowed for the cheap and easy production of fertilizers in bulk. Conversely, the descendants of the victims of Haber’s gas attacks (including those killed by Zyklon B) are not here.

Real life “villains” are complex characters indeed.

More:

Fritz Haber’s Experiments in Life and Death

Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons

Chemical and Engineering News: 100 Years of Chemical Weapons