Marvel’s X-Men books have relaunched, and relaunched in a big, big way with two new #1s in two weeks: House of X #1 and Powers of X #1 (that’s “powers of 10” actually) – both written by Jonathan Hickman. In the two titles – bi-weekly in their six-issue runs through October – Hickman is telling a sprawling story that covers now, 10 years from now, 100 years in the future and 1000 years in the future. That’s the “powers of ten” thing, right there.

By the way, both issues are still available at your local comic shops (find yours here) as well as digitally, at Comixology.com. Both series are worth the read.

In telling his story, Hickman is explaining the rise and fall of mutants, and part of it, somewhere around the year 100 (referred to as X2) takes a hard dive into biology.

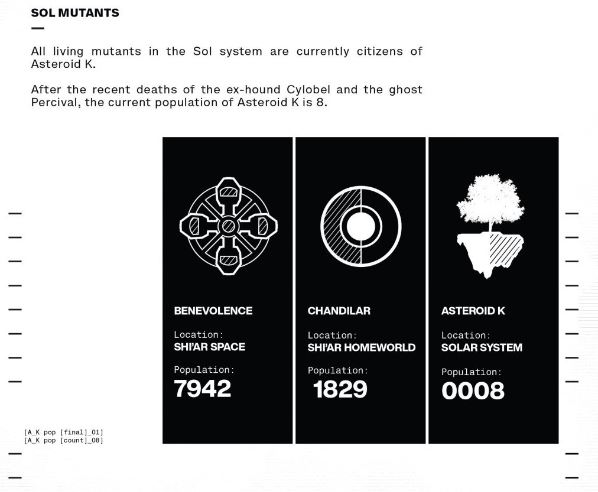

According to a text piece Hickman often sprinkles through his work, the mutant population on earth fell to non-sustainable levels somewhere prior to the year 100 mark we’re shown in the series. This resulted in the remaining mutant leadership approving the “Sinister breeding pits of Mars.” Yeah – even though they’re named after the X-Men enemy, but yet, genius mutant geneticist Mister Sinister, that’s a really…problematic name.

“non-sustainable levels” – where the mutants are by X2 (c) Marvel

Anyway – an outline of Sinister’s breeding program is laid out by Hickman, and it went like this:

- Copy ideas of the Sentinel/HOUND program, but rather than create mutants with traits that lent themselves to detection, deception, and hunting other mutants, focus on traits that were more militaristic and aggressive in nature.

- The first “generation” were copies of a singular DNA source with pure X-genes. These were soldiers, “fodder” as they are called, who fought to defend the mutant nation-state of Krakoa.

- The second “generation” was called a “Chimera” generation, which had DNA which contained two distinct X-genes, resulting in a mutant with a “mostly” predictable combined power set of the source mutants.

- The third generation was also called a “Chimera” generation and was made up of mutants with an amalgamated DNA that contained up to five X-genes. These creations were mostly successful, albeit with a predictable, 10% failure rate – which were peace-seeking mutants who were called “Cardinal.”

- The fourth generation is where it all fell apart, due to a corrupted hive mind in production (possibly caused by Sinister himself). Generation 4 killed off 40% of the remaining mutant population, caused the fall of Krakoa, and then committed mass suicide.

Man, mutants cannot catch a break.

It’s that word used to describe the second and third generations that I’m looking at: chimera, or, as Hickman uses it: Chimera.

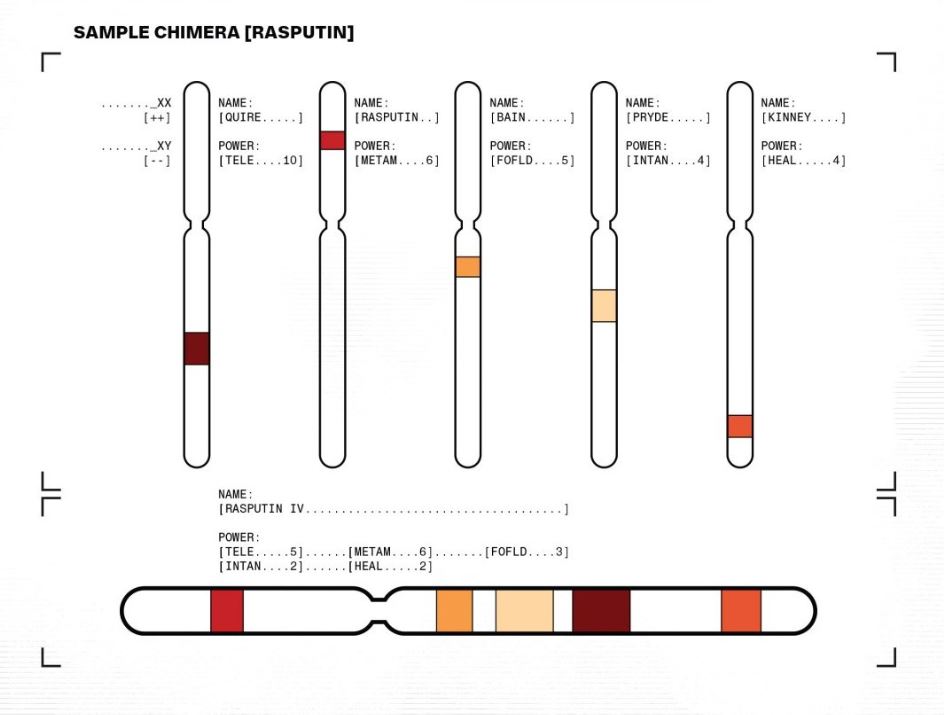

The main protagonist in Powers of X #1 is Rasputin – a Chimera whose DNA shows that it contains X-gene contributions from Quentin Quire, Colossus, Unus the Untouchable, Kitty Pryde and X-23. A nice mash-up.

As it’s in the news, and there’s plenty of confusion to go around, let’s look at the science of that thing – a “chimera.”

But first – terms.

Making Copies and Mixing Genes – A Glossary

It’s easy to get lost in the terms, so let’s lay some clear definitions out:

Clone: A copy of an individual. Identical DNA, so, therefore, largely identical appearance and possibly, but not guaranteed, personality. This is a tight match, tighter even than identical twins. Dolly the sheep was a clone, created from the cell of a mammary gland (and therefore named after Dolly Parton) of another sheep. I’m going with the assumption that Hickman’s first-generation were clones of original X-Men, or each other, as they were referred to as “copies.”

Sarah Manning – and her clones from Orphan Black (c) BBC

Mutant/Mutation: Genetically, a mutation is any change in the DNA of an organism, and this change results in the mutant form of a gene, protein or other expressions of that particular stretch of the DNA. There are many different causes of mutations of DNA. Some changes are fixed by DNA repair mechanisms, but if they’re not, they are passed along to daughter cells, and are expressed by the organism as its phenotype. We’re different than the Marvel Universe – the vast number of mutations in human DNA are hidden (they have no effect) or harmful. If the mutation leads to a phenotypic advantage that allows the organism to reproduce or use resources better than others (called natural selection), the chances that the mutation passes along to the next generation increase. Those small changes over time are what we call evolution. Organisms evolve over time to better match their environment. Strictly applying our universe’s rules of evolution to the Marvel Universe’s mutants is…problematic at best.

Hybrid: Offspring created from the breeding of two individuals which were different species, breeds, varieties or genera (plural of genus). Often sterile due to the differing number of chromosomes between the parents – and thus unable to split evenly in the formation of gametes, sometimes hybrids are fertile and “better” than either parent, thus showing what’s called “hybrid vigor,” such as say, Superboy. On our earth, hybrids are things like ligers (lion and tiger), mules (donkey and horse), beefalo, wolfdogs, and more. For decades, hybrids were seen as genetic anomalies and dead ends, but more and more, are being seen as possible ways to adapt to the changing environment and ensure survival.

A lion and a tiger met for drinks… Ligers can be huge thanks to hybrid vigor

Rumors that Wolverine is a hybrid are completely unfounded – although there was once a story going around that a weird, considered storyline twist for the character was that he was a mutant wolverine, not a mutant human. That’s just weird and makes you think long and hard about his years-long love interests like Jean Grey, Storm, Mariko, and about a zillion other female X-Men.

Mosaic: Single fertilized egg, more than one form of DNA (the genotype) inside. As a result, parts of the resulting organism have different DNA, and thus different cells with different phenotypes (the physical expression of the DNA, influenced by the environment). Organisms with different colored eyes – heterochromia iridum – (but not David Bowie) that unique feature sometimes owes its origin to being a mosaic. Different DNA is present in one eye compared to the other, resulting in different colors. Most often, genetic mosaicism is responsible for genetic diseases, such as mosaic Downs syndrome, Turner syndrome, Trisomy 18 and others.

Transgenic organism: Add or remove a gene from an organism in order to study the effects of that particular gene, and that thing you’ve made is a transgenic organism. The “trans” suffix there means “across,” which is often the case, as additional genes can cross species lines. Remove or disable a gene in order to study what that gene does in the organism, and you’ve created a “knock-out” variant of that organism. Transgenic organisms are widely known as “genetically modified” organisms or GMOs. Most often with successful GMOs, the resultant organism shows its own phenotype (how its genotype is expressed), along with the added gene of interest also expressed. These new genes can be visible (such as glow in the dark features) or invisible (such as changes in the amount of nutrients they contain). Keep this idea of transgenic organisms in mind as we go on.

Chimera Basics

First and foremost, through his previous work, Hickman has shown us that he’s no dummy. He does his research and knows his science. I’m 100% behind the idea that Hickman (and this is given away by his turning the word into a proper noun via capitalization) is using “Chimera” as figurative, rather than a literal thing as defined in science.

Admittedly, it’s a sweet storytelling move – it gives him the latitude and hand-wavey science basis to do what all X-Men fans have done since they became X-Men fans… “Oh yeah, well, if Kitty Pryde and Colossus had a kid, it would have steel skin and be able to phase through solid objects!” Comic store and con floor discussions have been put into the X-Men canon. Solid.

Mythologically, the original chimera was from the Greek and was a lion with a goat coming out of its back and a tail that, depending upon the interpretation, could be a snake. Three animals in one. There are loads of other chimera examples in mythology and fiction, and they all share the same general idea – smash two or more animals together. Heck, you had one prominently in your childhood: Beast from Beauty and the Beast – horns of a bison, back mane of a hyena, boar tusks, gorilla brows, a lion’s nose, and mane, the arms and chest of a bear, and the hind legs and tail of a wolf.

Beast – a total chimera. The different features came from different cells of the different organisms…oh, and magic! (c) Disney

That old witch did a real number on him.

Okay – biologically speaking, chimeras aren’t too much different. A genetic/biological chimera is a single organism that’s composed of cells of different genotypes (DNA) – not a hybrid, a transgenic organism, and technically, not a mosaic. By convention and most common definition, the DNA from chimeras comes from two different organisms.

Probably the most…famous(?) type of chimeras are tetragametic (made of four gametes – two eggs, two sperm cells). These are the “twin eaters.”

Jumping right from science into the fictional portrayals of chimerism, this is the stuff of CSI-style procedural shows where the person clearly did the crime, but the DNA doesn’t match because they, in the womb, absorbed their previously unknown, fraternal twin – something that’s rare, but can happen naturally, but has a higher incidence in in-vitro fertilization.

Some of the person’s cells carry the twin’s DNA, some of the cells carry their DNA. It’s been used enough that it’s become something of a trope, for instance, a rapist’s gametes are the DNA from the twin, but the blood is theirs, thus the DNA is very close, but not a match, and thus, no good in court, until the chimera card is tossed out, and then…justice is served and the credits roll.

Chimera Biology

But the thing with genetic chimeras is that there are two distinct DNA molecules that came from two different zygotes, and this results in two different cell lines (which came from two distinct people/organisms) in the one individual (remember – if they came from the same organism, that’s a mosaic). Animal chimeras can form when one fertilized zygote absorbs another, as the result of transplantation (organ or bone marrow for example), and experimentally.

To create a chimera in the lab, embryonic cells from one animal are literally transplanted onto the embryo of another animal. This method has – as Mister Sinister of the X-Men world would call…an acceptable failure rate, but has led to the creation of the chimeric geep (a goat and sheep) which survived to adulthood, as well as chimeric mice with human glial cells injected into their brains and a human-sheep chimera whose blood was 15% human and 85% sheep. Chimeric mice are commonly used in research to investigate, in part, how one selection of cells is affected over another.

But the key to it all – two distinct sets of DNA, and therefore, tissues, in one organism. Along with that, offspring of chimeras – even if both parents are chimeras – do not get all the different DNA, thus making them chimeras as well. They only get the DNA that happens to be in the gametes of the parents. Sexual reproduction isn’t going to give you chimeras.

Hang tight – I’m getting back to the X-Men.

Why You’ve Heard About Chimeras Recently (And Not in the X-Men)

While Hickman’s X-Men relaunch/reboot is causing a stir in pop culture circles, it’s not the reason why you may have heard the word “chimera” in the news. As reported last week, a team of scientists in China has created an embryo containing both human and monkey cells. That’s a straight-up chimera, right there. The DNA was not blended – the resulting embryo contained both types of cells.

The goal of the experiment with monkey cells was to do the work in another animal cell line which wouldn’t reject the human cells as pigs and sheep would, and ultimately, to produce human organs…er, outside of humans, though the veracity of the claim is not without controversy.

It’s important to note that the human-monkey chimeras were not meant to be brought to term or implanted in a female. While the peer-reviewed version of the research is supposedly in review by a scientific journal, the story which was leaked to the press made it feel as if the experiment was a “proof of concept” vein of research, perhaps to attract attention and further funding. It did work, after all.

Um…Yeah

You probably caught a whiff of it in that last part. To talk about chimera creation is an ethical minefield. Missing from what I wrote about up there was the fact that the international team of scientists doing the experiment on the human-monkey chimera traveled to China in order to do it, as federal funds cannot be used to create human-monkey embryos in the US as per National Institutes of Health guidelines, and there are equally tight restrictions and guidelines in other countries. There are no such prohibitions in China – home of the CRISPR’d babies.

Ethically, human-anything chimeras are a nightmare. Ask just about any “what if?” question you’d like, and you get a messy, creepy answer.

Back to the X-Men

Let’s go with the idea that Mister Sinister is an amazing geneticist (spoiler, he is), an expert at manipulating mutant genes and their component DNA. There’s one thing you can’t get away from – the Sinister Breeding Pits would truly live up to their name.

No matter what he was making – clones of the first generation or Chimeras of generations two and three, they would all start at the same point – embryos. Now, it’s unclear what Hickman’s notes on Sinister’s “failure rate” mean, but if we look at our own success rates in cloning and making human-something chimeras, our success rate is dwarfed by our failure rate. Dwarfed.

Dolly the sheep – the “successful” clone? It took 277 eggs to create 29 viable embryos, and from there, three were born, and one, Dolly survived. Those are horrible odds.

The “successful” human-monkey chimera? That was the one that took. The research paper will report how many tries were needed.

If Sinister’s “failure rates” embryos that failed to take, then his abilities are phenomenal, far outstripping what we can do here and now, in our universe. His first generation – the clones…0.3% failure? That’s nuts. Our current best technique has a roughly 9% success rate. Of all the eggs, sperm and embryos used – 91% are failures. And that’s in agriculture. Primate cloning (which would include humans) is a lot, lot harder.

Sinister’s second and third generations, the Chimeras showed higher failure rates – 1.2% and 9.4%, respectively. Still – phenomenal when compared to our numbers, but yet – starting to climb – and not at a linear rate.

Now, this is a fictional universe, where a fictional mutant geneticist is creating fictional mutants in desperate times, but still…those failures…those were embryos that just didn’t work. Even at 1.2% for generation two…if your population is 1,000 individuals, that’s 120. Those numbers crank for higher failure rates.

Desperate times. Muddy ethics. Minister Sinister lives up to his name.

That’s MISTER Sinister to you. (c) Marvel

But Are They True Chimeras?

I’m going to restate my earlier claim – Hickman’s “Chimera” means a figurative, not genetic chimera. That’s what works with the mutants we’ve seen, and mutation as we understand it. Take Rasputin for example – if she was a true genetic chimera, then each power she displays (those of Colossus, Kitty Pryde, Unus, X-23, and Quentin Quire) comes from the DNA of those respective mutants, and thus, the respective cells in Rasputin’s body.

Rasputin’s powers – on the bottom image. Five power sets. Yikes (c) Marvel

If this works, then these X3 Chimera X-Men aren’t mutants. A mutant isn’t a chimera. Rasputin is a well-designed, genetic Frankenstein – by our standards. And just a note – that’s not what’s implied by the picture included in the issue shown above. The bi-lobed structure – that’s how chromosomes (made of DNA, and the home to genes) are usually depicted. Showing all five on one chromosome suggests that Rasputin has all five genes for the powers of the named mutants.

Also – it’s unclear how the mutants of generation two resulted in the mutants of generation three, who had five traits. Where did the fifth one come from? How do all of the X-Genes manage to make it from one generation to the next? Oh, if I could only spend an afternoon in Sinister’s lab. I mean, I’d be horrified, but still. There would be so much Marvel genetics to learn.

If I were a betting man, I’d put money that yes, Hickman’s “Chimera” are figurative in that sense, referring back to the mythological definition, but are actually transgenic organisms – GMO X-Men. GMO-Men? GMOmen? While the transfer of the genes responsible for powers from one generation to the next is still a little sketchy, they are still passed on – something that’s virtually impossible with true genetic chimeras. Transgenic organisms would be able to pass on their respective X-Genes, although distribution would be tricky – and perhaps that’s the root of the failure rate, embryos without the respective genes.

None of this is meant to take anything away from what Hickman is doing here at the start of what reportedly will be a long X-Men run. Rather, by calling the new X-Men characters figurative chimeras, he’s given himself room and freedom to play – mixing and matching powers and abilities of previous mutants with others to create wild new combos without tripping up on science. It’s a good time – and a fun time – to be an X-Men fan again.