Plague Doctors, huh? Want a weird coincidence?

Here we are in April of 2020, and – had the comic book industry continued running as usual, DC Comics would’ve released Hawkman #23 earlier this month, on April 8th. That’s a detail from the cover up there. The issue, written by Robert Vendetti, with art by Marcio Takara and Fernando Pasarin, would have/one day will introduce a new, hitherto unknown incarnation of the constantly-reincarnating Hawkman: the Plague Doctor.

The issue’s description reads:

Cloaked in black and wearing the eerie mask of a hawk, the mysterious Plague Doctor roams 17th century Europe in an attempt to ease the suffering of those who fall victim to the Black Death. But how is the Doctor supposed to help anyone when he’s hated and feared for his unique immunity to the disease? It’s mind versus body as Carter Hall relives his most tragic past life in a last stand to fight off Sky Tyrant’s control over his body for good!

Plague doctors show up frequently in pop culture, and why not? Their costumes are downright nightmare fuel. Ankle-length heavy black coats, boots, thick gloves, a hat with a wide brim and that mask – glass lenses hiding the eyes, and that long beak-like projection that certainly distorted and muffled the doctor’s voice to change it into some non-human sounding murmur.

From DC Comics’ Hellblazer #254 and #255. Points for mentioning miasma! (c) DC Comics

If you’ve marinated in pop culture, you’ve seen them around. The cosplay is a perennial favorite (and will probably come back into vogue even more now…) at comic cons, characters copying their costumes show up in comics, such as Hawkman, the “Merrymaker” character in Batman, Spider-Man Marvel: 1602, a brief appearance in Hellblazer; the novel and film version of Dan Brown’s Inferno, a mask can be spotted in the live-action version of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (Belle’s mom died of the plague); in Assassin’s Creed II, The Legend of Zelda, and many others, such as cameos in Adventure Time, My Little Pony, Disenchantment and My Hero Academia.

While not the most popular collective-unconscious-creepy-zeitgeist nightmare uniform out there (that’s still clowns), Plague Doctors are at the edges of our collective nightmares, ready to take that top spot if something happens with the clowns.

It’s no wonder that they have a high position in our collective feelings of “ick.” Historically, if a Plague Doctor showed up, things were really, really bad.

Like, “someone’s going to die,” bad.

Any exploration of Plague Doctors has to begin with their iconic costume. The design for the complete look is credited to the French physician, Charles de Lorme in the early 1600s, who designed it out of harsh necessity: the bubonic plague.

de Lorme’s idea with the gear was that it would be protective in nature, much like the armor worn by knights into battle. The thing though is that for his early good intentions, de Lorne’s “enemy” wasn’t Yersinia pestis, the bacteria responsible for the plague that rode along in fleas and was transferred via bite. This was pre-germ theory medicine. de Lorne’s efforts were designed to protect the doctor from the miasma from which the disease sprung.

Believe it or not, there are some weird parallels to what we’re living through today, too. Let’s talk about the history of medicine.

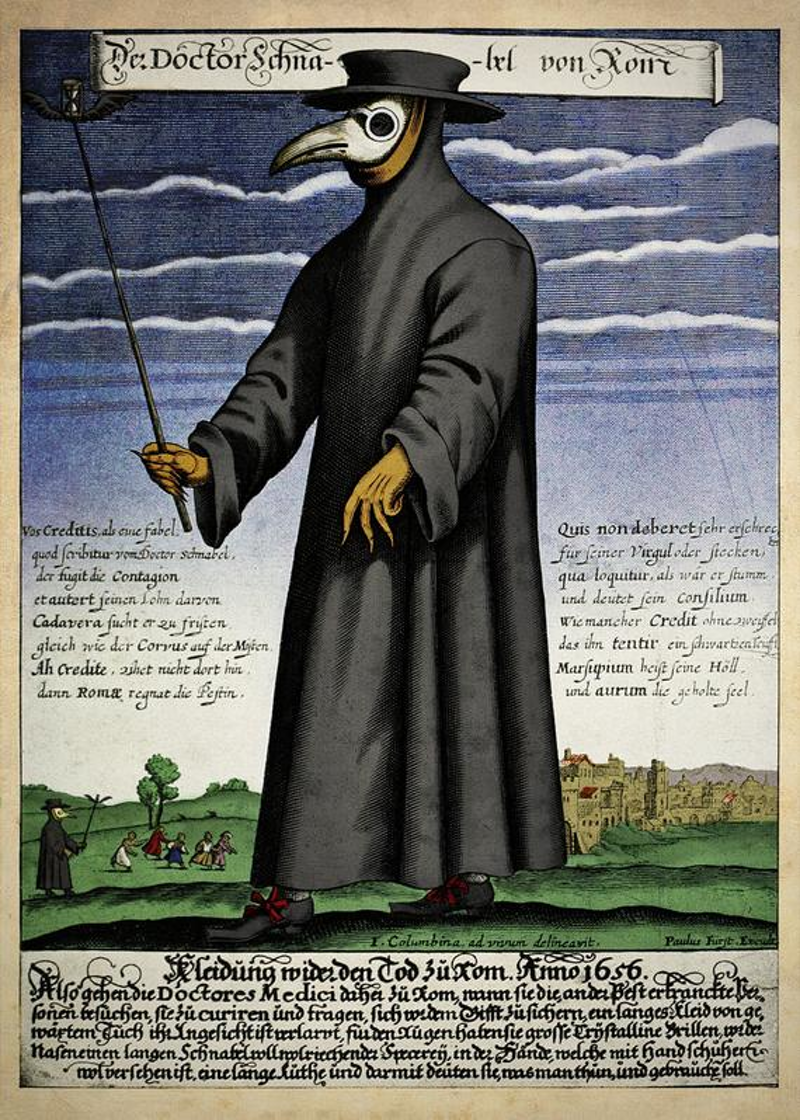

A color copper engraving of Doctor Schnabel [i.e Dr. Beak], a plague doctor in seventeenth-century Rome, published by Paul Fürst, ca. 1656

The Air is the Problem.

The miasma theory held that disease was spread and carried by, literally, “bad air.” The notion had first come to acceptance in ancient Greece and ancient China and held firmly in medicine for thousands of years. Miasma was thought to be responsible for any number of diseases such as cholera, malaria, the plague, influenza, chlamydia and more could all trace their root cause back to this, noxious air.

You may want to think that the doctors of the ancient medical world were kind of on to something here with miasma – after all, some diseases are airborne, right? Protect yourself from “bad air” and you don’t get whatever bug is going around, yeah? Miasma’s kind of just a pre-germ germ theory, right?

Yeah, but – while some, okay, a very limited number of the diseases listed above…and seriously, not chlamydia – might be transported through the air, the “bad air” itself isn’t what causes the disease. It’s the infectious particles that might be in the air. But the idea stuck for thousands of years, and from its (in retrospect) fantastical basis – “bad air” – many equally fantastic ideas were suggested and accepted. This really wrong intellectual road held an amazingly strong grip in early medicine and anyone who challenged often found themselves crushed by the institutions and their defenders of the day.

Seriously – though growing evidence was starting to show “bad air” might not be what was causing disease, miasma theory held sway through the late 1800s. Even the work, as definitive as it was, of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, and the evidence of the effectiveness of antiseptics demonstrated by Joseph Lister (yeah…) had many strong, loud and respected critics. Want a horrible story to think about with how the medical institution was slow to come around to the idea that disease was caused by stuff and not bad air? Read up on Ignaz Semmelweis, or just listen to the Radiolab podcast that briefly relates his story here. Spoilers: not a happy ending.

Miasma branches were pervasive and insidious over time. “Bad air” caused disease? Bad air could be seen as coming from an angry (or perhaps petulant) god, looking to make some of his people sick. Where do you find bad air? Why, it’s probably created around bad people, because good people wouldn’t create bad air. Weirdly, the diseases caused by bad air often flared up in the crowded, cramped neighborhoods of the city’s poor, or among those not acceptable in society’s eyes. With just a little bit of work, you could get miasma theory to justify a lot of pretty lousy ways to treat people.

And even though miasma theory was defeated in “modern” medical thought with Robert Koch’s findings with anthrax, it kept cropping up in stubborn little ways here and there throughout the early 20th century until…basically, and tragically in a way, its proponents took the belief of miasma into the ground with them when they died of old age. Listen carefully to some anti-science arguments even today, and you can hear the bones of miasma theory rattling around.

Oh, and one terrific little pop culture note – one of the most significant early challengers of miasma theory? John Snow. A doctor in London in the mid-1800s, Snow realized that an 1854 cholera outbreak centered on Broad Street could be traced back to a single water pump from which the vast majority of the victims drew their water. Snow figured this out using maps, patient interviews, and statistics. He convinced the city government to remove the handle from the pump, and the cholera cases decreased immediately. A few years later though, Snow’s published report of his findings – that something in the water caused cholera, not the “bad air” in the neighborhood – was deemed not significant and dismissed. And critics piled on.

That mention about cleaning up sewage made by Tyrion Lannister in the final episode of Game of Thrones? A slight, nerdy nod to another John Snow.

Okay – sorry for the derail on miasma, back to Plague Doctors.

The Plague Doctor from Hawkman #23, (c) DC Comics

The Stylish, Fierce, and Functional Look for 1619 Italy and France

So, de Lorme’s idea was to protect the doctor from the plague – well, from the miasma that was causing the plague, so, he figured, the outfit should protect the wearer from exposure to the air. As such, the coat was heavy and rather impermeable – either leather or waxed canvas. Gloves go without saying, but Plague Doctors also carried canes – or more accurately, staffs. Staves. Whatever.

The staff of the Plague Doctor was long – approaching six feet (social distancing, anyone) – and was designed so that the doctor did not have to get close to the patient while using it to perform any number of actions: point to things of interest, remove the patient’s clothes, examine specific areas, poke at dead plague victims’ innards and of course, keep people away.

Hey – just in case you want to go there, though – not really. The six-foot rule we’re being told to follow today doesn’t come from 17th-century nightmare fuel dudes. It comes from studies done on airlines.

The Plague Doctor’s hat was often an indication of their station. You weren’t anything back in the day if you didn’t have a special hat that said who you were.

And then there was the mask. Holy. Crap.

de Lorme wanted to keep doctors safe from the miasms, so that meant strictly limiting the air to which the doctor would be exposed. That meant a full hood and face mask. Glass lenses went over the eye holes, and even though much of the gear was made in Italy, and the Italians were pretty good with lens-making, the lenses of the mask would often be seen by the public as blank disks. Sometimes, black lines were drawn, connecting the two eye holes to suggest the glasses worn by the doctors.

The “beak” of the mask was an early take at a respirator, and was most often stuffed with sweet-smelling herbs and spices – after all, dead plague victims didn’t smell…great. Air could come in through small holes along the extension, and pass through the material meant to perfume and counteract the “evil” smells that were causing the plague. The collection of material was often theriac, a compound that often included viper flesh powder, lavender, dried mentha, cinnamon, myrrh, and honey. Occasionally, masks were outfitted with sponges that had been soaked in vinegar as well. The coat was often loaded up with the same herbs and spices.

Long cloak, no eyes, long beak, staff, weird hat. The appearance of the Plague Doctors’ uniform quickly – and rightly so – became associated with mass death, and worked its way into both the collective unconscious and literature – where their reputation ranged from benevolent (they tried to help) to objects of satire and scorn (ultimately, they did nothing), to objects of terror (hey – maybe they didn’t follow the death, maybe these inhuman, bird-like things summoned the death).

Hawkman #23, cover (c) DC Comics

This Was Not a Long-Term Gig

“Doctors” in the 1600s weren’t what we would call “doctors” today. There was the whole miasma thing, the prohibition of opening up dead bodies to see what was inside to maybe help the living, and you know, just the whole “mystery” of what’s living and what’s not that kept the Plague Doctors from doing that much of anything for the hundreds of thousands of people that would die in an outbreak of the plague.

The inexperience and lack of knowledge of the Plague Doctors often got them in the end, as many would fall victim to the same plague they were attempting to treat.

As we’re being told today, when removing the material that may have been exposed to the contagion (masks today, funky horror-show bird suit then), treat it as if it has definitely been exposed to the contagion. Wash the personal protective equipment thoroughly if it’s reusable, or throw it away if it’s not. Don’t keep your cloak and mask, which may have patient fluids and/or fleas on them, in the same room you sleep and eat in.

In case you’re worried, the costume’s designer fared much better than those who wore the garb – de Lorme died on December 31st, 1678, at a reported 97 years old.

The Doctors Today

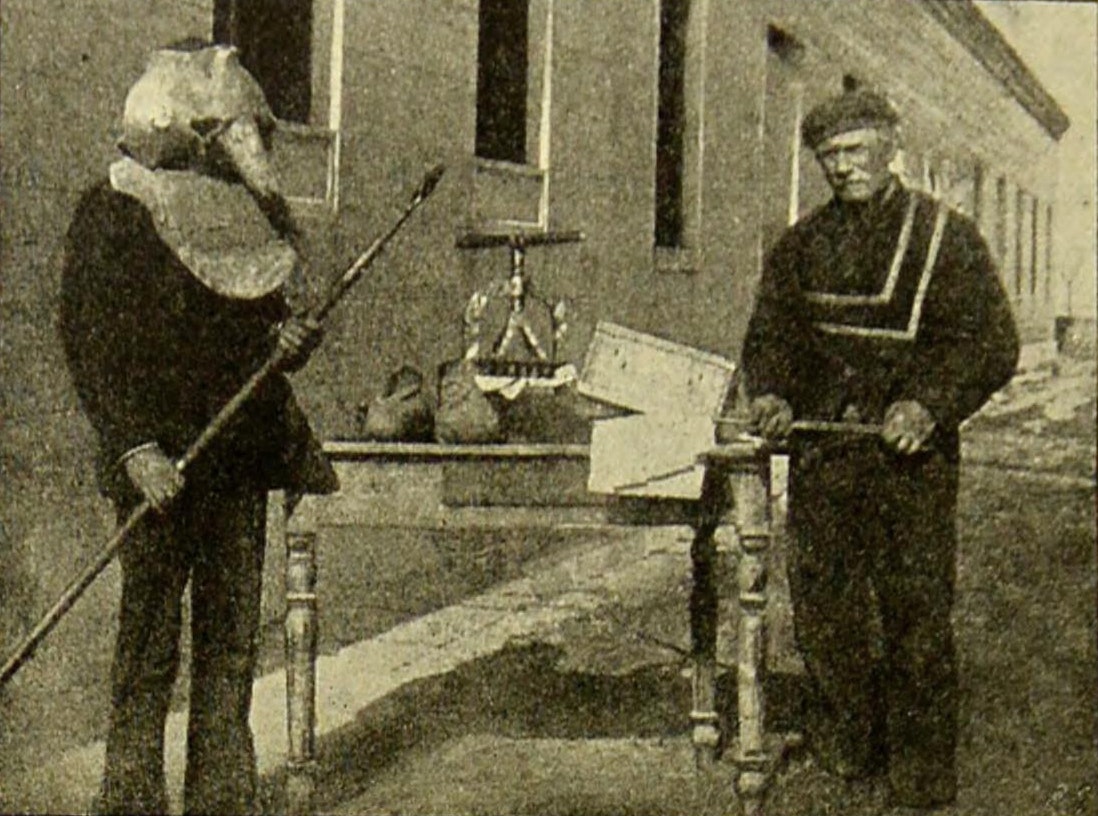

First off – remember that thing about miasma theory hanging around forever in medicine? Check this, from The Public Domain Review collection of Plague Doctor images.

A more recent Plague Doctor

That dude on the left that you’re going to see again in the shadows of your bedroom around 3:00 am this morning? Yeah, that image os from 1899. Righting off the miasma theory seriously took a long, long time.

As mentioned earlier, the image of the Plague Doctor remains embedded in popular culture today, more than 400 years after its introduction. The persistence of the image is largely due to both enshrinement and use in Italian (particularly Venetian) culture, where a mask-wearing character became a staple in Italian commedia dell’arte and cultural festivals. Traditional and more stylized Plague Doctor masks can be found for sale throughout Venice throughout the year, and are often worn during large festivals.

This year’s festivals, where many people would have undoubtedly worn the costume of the traditional Plague Doctor, were canceled due to the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak.