Cats and dogs are not equal.

Yeah, stunning conclusion right there, huh? Thank you for coming to my TED Talk.

But what may have caught your attention in recent days in the COVID-19 news coverage is that cats can apparently be infected by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. More than just cats, their larger cousins, lions, and tigers can be infected as well. A total of seven tigers and lions tested positive for the disease at the Bronx Zoo (all have recovered), and India’s National Conversation Authority has expressed concern over the virus being passed from humans and infecting the country’s threatened tiger population.

Stop looking at your cat like that. It’s not their fault.

And the reason your dog is smiling? It’s tougher for dogs to be infected – to the point that dogs may not be able to be infected by SARS-CoV-2.

Why one over the other? Is this just a cruel trick on cats?

To understand those questions and more, let’s look at how SARS-CoV-2 works.

SARS-CoV-2 Has a Key to the Door

It’s been known since shortly after the 2003 SARS-CoV outbreak that SARS-CoV doesn’t just bash any cell in a host’s body open, jam its genetic material inside, and force that cell to make more copies of itself. It’s a little more subdued. What was shown to be true for SARS-CoV in 2003 has also been shown to be true for CoV-2: it gets into cells through the ACE2 enzyme.

The ACE2 (short for angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) receptor can be found in two places – either freely floating in the extracellular matrix or tetherd to the surface of cells. It’s that latter case – on cell surfaces that seems to be where it interacts with SARS-CoV-2. Under normal functions, ACE2 grabs the circulating peptide angiotensin II (a vasoconstrictor) and modifies it into the angiotensin 1-7 peptide (a vasodilator). ACE2 can interact with a number of other peptides as well, looking for a specific structural component on each, which it recognizes and binds to.

Cells rich in surface ACE2 can be found throughout the human body, and the cells that line the respiratory tract – such as the epithelial cells in the nasal pathway and the cells that line alveoli (air sacs) in the lungs are particularly loaded. ACE2 is also found on the surface of cells in the small intestine, the liver, the colon, the lymph nodes, in bone marrow, the spleen, the kidney, and the brain.

It would be a real shame if someone were to hijack that nice ACE2 on the surface of a cell and use it for nefarious purposes, wouldn’t it?

SARS-CoV-2 is just the thing to do it.

The “CoV” of the virus’s name means that it is a coronavirus, which has a very specific shape and structure that we all probably see when we close our eyes at this point.

You know it, you love it, you’re sick of looking at it – its an artists representation of SARS-CoV-2 (c) NC State

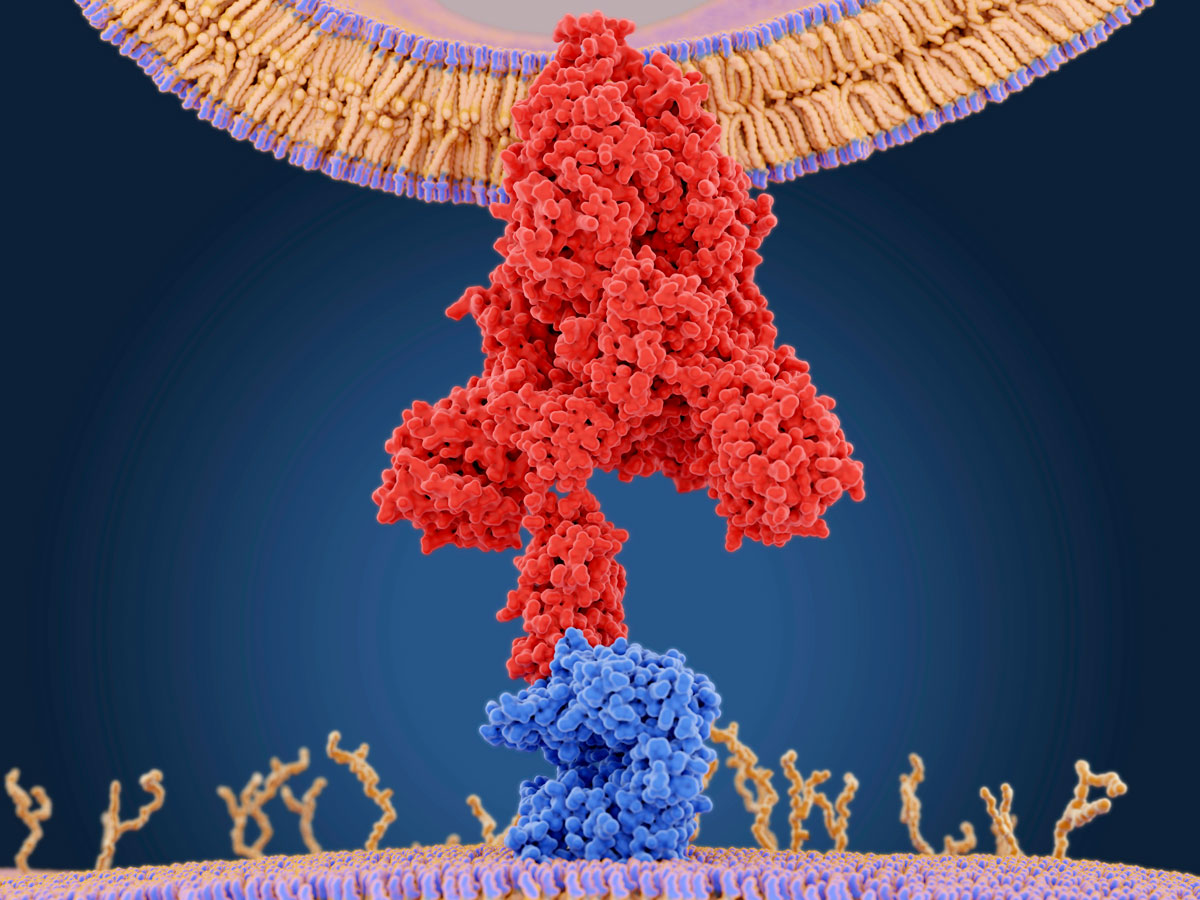

The virus got the “corona” in its name due to the “crown” of spikes that come out of its surface that makes it look both beautiful and deadly. Among the spikes is the SARS-CoV-2 specific “spike protein,” or S-protein. That’s the part of the virus that latches on to the receptor. There’s a fair amount of biochemistry that goes along with the parts that recognize each other, but essentially, once the spike protein is attached to the receptor, the virus’ shell or “envelope” is able to fuse with the target cell’s membrane. With the virus and cell membranes now effectively the same continuous membrane, the viral genetic material is free to move into the cell. And just to complete the picture of Virus 101, the virus’ genetic material hijacks the cell’s “machinery” instructing it to make copies of the virus, instead of whatever it was doing.

Also interesting – the unique spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 makes it an attractive target for a vaccine.

That’s the spike protein (red) coming in from the top to an ACE2 receptor (blue) on the cell’s surface on the bottom. Juan Gartner/Science Photo Library. Source

Need a quick and simple analogy? A robotic burglar with new software is looking to break into a specific factory that’s loaded with 3D printers. The robot burglar has a key that unlocks a specific door to the specific factory, which it uses. The burglar breaks in finds the factory’s main computer and reprograms it with its software. The factory stops producing its things, and immediately hums to life, printing more robotic burglars with their own keys and software.

Okay – to add a slightly unconnected wrinkle to this analogy, every now and then the instructions are misread in the factory and some bonkers robotic burglars are created that do similar, but different things. Those are mutant robots. Bringing this back to viruses – those would be the mutant strains of the SARS-CoV-2 that you hear about now and then. Some work as well as the main virus, some work better, some fall apart as soon as they leave the cell, some are harmless.

A quick couple of non-cat-related notes on ACE2 receptors: since they are part of the body’s natural blood pressure control system, they’re often a target for medicines that seek to control blood pressure. Two types specifically, ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers both act (in rodent models) to upregulate – cause more to be made – ACE2 on cell surfaces. More receptors, more spots for angiotensin II to be changed into angiotensin 1-7, which acts to reduce blood pressure.

But also – more ACE2 on cell surfaces – perhaps more spots for SARS-CoV-2 to land, and perhaps people taking the medicines, which are in many cases, lifesaving, are more susceptible to infection by the virus.

And also, part two – research indicates that current smokers and individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) tend to have more ACE2 on the surfaces of cells in their lungs, which could suggest that those individuals may be at greater risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Yeah, But What About My Cat?

Humans aren’t the only things that use this original peptide to manage blood pressure or other functions It’s thought that angiotensin 2 is virtually universal among vertebrates – animals with backbones – and that’s a massive group – mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians. But that doesn’t mean that every vertebrate is susceptible to SARS-CoV-2. Thank evolution for that.

“Thanks evolution!” says the man-tiger who would most likely catch SARS-CoV-2 (c) Kellogg’s

Over millions of years since a common ancestor to modern vertebrates adopted what we’ve come to call the angiotensin-renin system, small changes have occurred in its pieces. These small changes in the sequence of DNA coding for the players in the angiotensin-renin system – the peptides, the components that produce them, their receptors, everything – have shaped what we have in modern vertebrates. If these changes were useful and benefitted the organism, they were passed on to future generations. If they offered no reproductive advantage to the organism, they weren’t. That’s evolution.

Run that clock for millions of years, develop into countless species, each going through their own respective evolution. While the angiotensin-renin system seems to be conservative, that is, vertebrates still show parts that are virtually identical to others, changes have been introduced that made them different. Think of lines moving upward that sometimes move towards or away from one another over time, and occasionally lie on top of one another.

We’re getting back to your cat.

As reported in Trends in Molecular Medicine in March, the sequence of amino acids that make up the ACE2 receptor region that binds to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is only a little bit different (“a few exchanges” is how it’s said) when you compare humans and cats, along with some other animals, like ferrets.

That similarity right there – the thing that apparently makes it possible for SARS-CoV-2 to bind to both cat (and ferrets, orangutans, monkeys, some bats and perhaps pangolin) and humans ACE2 is part of the basic mechanism that allows viruses to jump from one species to another. All it takes is exposure to the virus from one species to another, and you’re off to the races. If an animal has a virus that exploits a system that another animal doesn’t share, then there’s no, or very limited infection since the virus can’t jump across the species boundary, or can’t jump it very effectively.

This ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect cats seems to be supported by a study which dosed three cats with high concentrations of the virus and found both viral RNA and infectious viral particles in their upper respiratory tracts five days later when the animals were euthanized. When three additional infected cats were paired with uninfected cats and placed in adjacent cages, viral particles were found in one of the three exposed cats, suggesting that the infected cat with which it was paired both had a large enough viral load in its respiratory tract and was able to spread it via respiration. All three initially infected cats, as well as the one exposed cat showed antibodies to the virus as well.

Garfield’s weight would be considered a co-morbidity. (c) Paws, Inc.

Later tests in the same study indicated that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can replicate efficiently in the animals, the infection apparently caused lesions in the nasal and tracheal tissue layers, as well as lesions in the lungs. The lesions were reported by the researchers as “massive.” But – and this is interesting – the infected cats did not show COVID-19 symptoms.

While the cats were inoculated with very high – perhaps even artificially so – levels of the virus for the study, some investigators are suggesting that viral the load used to infect the cats may be seen in the closed living areas of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. This method of transmission was suggested in 2004, related to the SARS outbreak in China during the spring of 2003.

So – cats, the big picture? Evidence strongly suggests that they can be infected by SARS-CoV-2, but to what extent, and whether or not they die from COVID-19 complications is not yet known. More research is needed.

Okay, So What About My Dog?

Cats’ ACE2 receptor looks a lot like that of humans, which allows the SARS-CoV-2 virus to infect cells. What about dogs?

Remember that bit about evolution earlier? The ACE2 of dogs has varied away from the version that’s common to humans and cats, and as a result, it appears that SARS-CoV-2 isn’t able to effectively infect dogs.

While there have been two reports of at least dogs testing positive for the virus, when tested in the lab, the virus replicated poorly in dogs, as well as pigs, chickens, and ducks. No one is saying that the animals are straight-up immune to SARS-CoV-2 though. The ACE2/spike protein interaction is just part of the story behind infection by the virus. In virtually all of the animals tested, some virus was found. In dogs, it was found in their poop (which was certainly interesting to them), but not in their respiratory pathways or organs. This, the researchers concluded that dogs have a low susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2. In other words, the virus wasn’t able to make a home in the most common areas seen in infected animals (cats, humans, etc.). “Making a home” would indicate a spike protein-ACE2 connection.

In addition to cats and dogs, the study mentioned also showed that ferrets were highly susceptible to the virus, while pigs, chickens, and ducks were on the dog side of the line – that is, not susceptible to the virus.

You’re safe, Scoob. (c) WB

Without a full genetic and structural analysis its impossible to know if this low susceptibility to the virus is due only to a different ACE2 receptor, but based on what is known about how the virus infects, it is suggestive that a difference in receptors between species does play a role.

Okay – that last bit was a little off in regards to this stuff being a complete genetic unknown. Want to geek out for a second on the structure of ACE2? Check it:

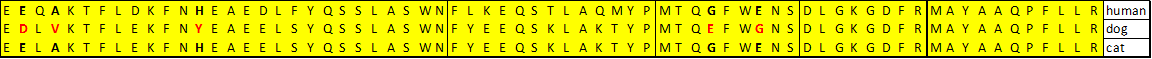

Okay – some explanation here: This is the listing of the amino acids that make up the surface of ACE2 where the spike protein attaches. There are five sequences/chunks here that do the interacting with the spike protein, divided by the vertical lines. These are the 69 amino acids that are within 10 angstroms of the spike protein (a human hair is about a million angstroms across). Dogs and cats have five amino acids that are different – but look at humans and cats, yeah? Nearly identical. Why is a dog different than cats and humans? Again – thank evolution.

Not to get too much into the biochemistry, but the last three of the five are extremely different amino acid residues, the H->Y change is a positively charged-to-hydrophobic change and G-to-E is the simplest mere backbone of an amino acid (G) to a negatively charged residue change (E). We’re talking oil and water here. If it turns out that dogs cannot get COVID-19 by the entry of the viral genetic material via ACE2, while cats can; these simple residue changes may be the key.

Oh, and one more thing with the difference in the ACE2? Mice aren’t susceptible to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. They’re on Team Dog. But – when you genetically engineer mice so their ACE2 looks more like human ACE2? They’re susceptible to the virus.

Okay, now you can look at your cat like that…

Can I Catch COVID-19 From My Cat?

All evidence to date suggests that’s very unlikely your cat will infect you if it is infected, and also points to the viral pathway going from you to your cat. Not the other way around. Individuals with a positive COVID-19 test or symptoms should not be getting close to their pets, especially cats. The possibility of human-to-animal virus transmission is why many zoos quickly shut down, and after all, it’s most likely that the lions and tigers that tested positive for the virus at the Bronx zoo got it from an infected handler. And there is a worry about humans infecting wild animals which would then take it back into their populations – like the concern about the tigers in India.

Right now – no one considers cats as a viable factor in the spread of SARS-CoV-2. That’s not based on the most recent study, but rather, on research that was done during the 2003 outbreak that showed (you see this coming, right?) that while cats and ferrets are susceptible to the SARS-CoV virus, the transmission of the virus from them to humans is…meh, at best. In virology-speak, ferrets and cats are not viable reservoirs of the virus into the human population. But – as we learn with this virus every day…things can change in light of new data. While it looks likely that cats don’t spread the SARS-CoV-2 virus to humans, it’s not 100% proven. Err on the side of caution.

That said, experts recommend that when it comes to your cat (and other pets) now’s the time to shift outside-for-inside – outside cats need to be taught about the comforts of living inside 24/7. Let’s say – worst-case scenario – cats can spread SARS-CoV-2, and an outdoor cat comes in contact with the virus outside, and then comes inside due to their in/out habits. Let’s not risk that. Bring the cat in and keep it in. Besides, it’s lousy for the native songbird population in your community.

Absolute worst case? Let’s say someone has a cat that wanders around outside during the day, and comes inside at night. Let’s say that cat is like Six Dinner Sid by Inga Moore and has a pretty active social life with any number of people in the community. A community where COVID-19 is spreading. Let’s say Sid (yeah, we’ll name the cat) gets some close snuggles and cuddles from an asymptomatic individual who is spreading the SARS-CoV-2 virus (that’s one of the reasons we’re wearing masks now), and Sid gets infected. Little kitty runny nose, little kitty sneeze, but otherwise okay. Meanwhile, at Sid’s house, Sid poops and pees in his litter box. Maybe a squirt of pee around the house as well, and maybe a rage poop because Sid’s owner does something to offend Sid. SARS-CoV-2 can travel in cat feces. Let’s say Sid’s owner isn’t always…quick with the cleanup, or maybe working 12-hour shifts and misses Sid’s messes for a day or two. Basically, Sid could be contaminating the living space that he lets his person share with him with SARS-CoV-2. That would be bad. Real bad.

Keep Sid inside.

Yeah, Sid – we know what you did. You little Typhoid Mary, you…

But by all means, stop giving your cats the side-eye – they can’t help their genetics and evolution.

Oh, and stop thinking about getting a pet bat – they carry it for sure.

The CDC has some guidelines for keeping and interacting with animals that it’s probably worth a minute to check out over here.

A final word on pets now’s the time to build and use that human-animal bond, not dissolve it. Other humans may give you COVID-19, but your cat most likely won’t. It’s only going to give you love.

Yeah – right. It’s a cat. It will give you a look of annoyance.

You might want to get a dog.

Special thanks to Brian Westwood for explaining the ACE2-spike protein connection and sequences.