Let’s talk about the Gorn.

First introduced in the Star Trek: The Original Series episode “Arena,” the Gorn morphed from a guy in an off-the-rack monster suit to a Xenomorph/Predator-esque threat with their own spin. Now, 56 years later, they’re a chilling threat to the Federation in Star Trek: Strange New Worlds. They first made themselves known in season 1, and … yeah, that season 2 cliffhanger.

And holy crap, they’re tough. And scary.

To help dig into the science of the Gorn, I sought some help from Dr. Mohammed Noor, a biology professor at Duke University and author of Live Long and Evolve: What Star Trek Can Teach Us About Evolution, Genetics, and Life on Other Worlds, and, as he calls it, an “occasional Star Trek science consultant.”

Noor’s YouTube channel, BioTrekkie Explains, features Noor as well as his semi-regular guest, actor Jayne Brook who played Admiral Katrina Cornwell on Star Trek: Discovery. Together, they dig into the life science of all the Treks. Aside to Biology students and STEM teachers — it’s a great review of major concepts of the science.

Before we get into the possibilities and plausibilities, from the start, this is chiefly about the modern Strange New Worlds Gorn. They’ve shown up in many places throughout Star Trek canon, with each iteration a little bit off from what was seen before.

That said, a quick run-down of modern-day Gorn would be useful. What we know about the Gorn so far:

- They are quadrupedal reptiles in their early life and later bipeds(?).

- They are reportedly cold-blooded, slowed, and/or killed by extremely low temperatures.

- They have at least two distinct life stages – hatching/juvenile and adult. Both have tails.

- They are social or interact in social groups towards a common goal or outcome. Their larger governmental organization is the Gorn Hegemony, located in the Beta Quadrant of the galaxy.

- They implant parasitic eggs in other warm-blooded life forms.

- They are cunning hunters, often using bait to lure other prey.

- They hunt humanoids, deposit eggs in them, and relocate them to “breeder worlds,” where the eggs hatch from the humanoids. Some humanoids are hunted for “sport.”

- Hatchings can lay eggs in hosts, presumably without sexual reproduction.

- The eggs are contained in the saliva/venom of the Gorn. Get sprayed, and you’re a baby factory.

- The hatched offspring compete, killing one another until only the strongest Gorn survives.

- Mature Gorn return to the breeder worlds to “harvest” the strongest, surviving Gorn. The sole survivor is taken to the homeworld or placed in a “liferaft” and sent into space to get even tougher.

- Their civilization has developed warp capabilities and protective gear for being in space.

- Through some unknown adaptation or technology, Gorn can survive being in the vacuum of space.

That’s a long, scary list.

If we hold it against earth-based science, how do some major Gorn characteristics check out? That’s what Dr. Noor is here for.

The “Cold-Blooded” Reptile Thing…

“I was absolutely thrilled to see the Gorn come back, and it’s nice seeing more biology around it, as opposed to just sort of the stereotype of like, oh, it’s a reptile, it’s slow and kind of dumb,” Noor says. “They’re not necessarily slow. Especially that original reptile on a hot planet — there’s no reason for it to be slow. Or even cold-blooded, really.”

Matching Gorn biology with what we know about large reptiles that once dominated our planet, there is an argument to be made that, given their activity level, Gorn are warm-blooded. Since the 1960s, there has been a growing consensus that dinosaurs were warm-blooded. While recent research strongly suggests that some herbivores like Stegosaurus and Triceratops and ancestors of modern cold-blooded reptiles lost that ability, many kept it.

Dinosaurs that maintained their warm-blooded physiology included the large group of Ornithischian (“bird-hipped”) dinosaurs, including the Saurischian (“lizard-hipped”) dinosaurs. Saurischians included Velociraptors, Tyrannosaurus, and their present-day, warm-blooded descendants, birds.

Gorn. Warm-blooded space dinosaurs.

The Social Reptile Thing…

Don’t let your mammal-centric feelings about solitary snakes color your judgment.

“Reptiles are an incredibly broad group,” Noor says. “We see birds working together, sometimes with what seems like a surprising level of intelligence. “And there’s a large body of evidence to suggest that, along with some modern reptiles, many types of dinosaurs operated in social groups and hunted in packs.”

Remember Jurassic Park?

“It was long and erroneously thought that reptiles were non-social, but that’s just not true,” Noor says. “Part of that comes from comparing parental care between reptiles and mammals and birds, there’s a lot less. A study says that 97% of reptile species abandoned their eggs soon after laying. That’s a pretty small involvement. But that three percent…

“Just a couple of examples – some Australian skinks live in monogamous family groupings. So not just mother and father but with their aunts and uncles and others. They’ll live together socially and interact socially. Alligators in Florida are known for having large groups of up to a hundred animals, and within those groups, you can see courtship dances and other behaviors that suggest a hierarchy. Even tortoises, which people tend to think of as slow, both in terms of physical speed and also maybe in terms of mental speed, have been shown that they can actually learn from watching others. It’s not outrageous that we see intelligent and interactive reptiles like these Gorn in the episodes. We should just be thankful we don’t have them on Earth. They seem to have their act together as a species.”

The Killing Brothers and Sisters Thing…

That’s the Gorn’s very Shakespearean twist – siblicide.

Someone may occasionally want to “kill” a brother or sister, but the Gorn take it to the next level. Shortly after emerging from the host, they go after one another. It’s a creepy, horrific thing as seen in Strange New Worlds.

It’s also seen here.

“There are cases on Earth, but we don’t really know the animals do it,” Noor said. “This has been studied in boobies — the bird with the unfortunate name — and with them, it’s related to resource scarcity. Basically, the parents are producing more offspring than can survive in the given environment, so it’s every baby for themselves.”

In the case of the boobies, the siblicide will result in one hatchling growing larger and stronger than the others, which it kills in turn or throws from the nest for other predators to pick off.

“It’s certainly not a pretty side of nature,” Noor said. “We tend to see more cooperation between siblings than siblicide. But if resources are limited – it’s better that one makes it than none make it to pass on the genes to the next generation. It wasn’t siblicide, but Star Trek has touched on this idea in the original series episode, ‘The Conscience of the King.’ The crew suspected that the actor was actually Kodos the Executioner, who had put 8000 colonists to death because there weren’t resources for the entire colony.

“Also — siblicide, in a way, is a hedge against incest and all the problems that can bring, genetically. It’s difficult to mate with your sibling if you’ve killed and eaten all your siblings. The behavior isn’t entirely uncommon, but when it happens between siblings — especially those just hatched — it makes us sit up and notice.”

The behavior is easily explained with the Gorn — the toughest sibling survives. As the stories suggest, mature Gorn return to a hatchling world to pick up the survivor, either to bring them to the home planet or toss them into a “lifeboat” and then into space to keep that “survival of the fittest” thing going.

That’s rough.

The Egg-Spraying Thing…

Gorn hatchings (and presumably their other forms) spray anything that gets too close to them with a venom that can blind their target but also is loaded with eggs. The eggs enter the host body through the mucus membranes or burrow through the skin and start to develop. Sometime later, they hatch and eat their way out of the host.

Hope you’re not eating because this directly correlates to animals on Earth.

“There’s a freshwater mussel genus called lampsillis in many places that has a little bit of itself that extends outside of its shells and looks like something larger fish would like to eat,” Noor says. “But when the fish come to bite the lure, the mussel pulls it back inside and sprays the fish with a ton of baby mussels. These babies latch on to the fish’s gills, where they feed and grow. They often drop off when they reach a certain size after getting a ride on the fish for a few days to months. This fish may suffer a little bit, but usually, they live through the experience.”

But still — very Gorn-like, catching a spray of babies in the face.

But let’s look at the egg spray together with another aspect of Gorn reproductive physiology: the hatchlings are apparently loaded with viable eggs from the start and ready to spray anyone that gets near them.

Not unheard of. Aphids, for example, are “born pregnant.” Other animals follow these lines from birth, but let’s start with aphids as a simple example. Like wasps and ants, aphid males have single copies of their genome (haploid), while females have two copies (diploid). Aphid eggs can have either single or double copies, producing males or females. The baby female aphids are clones of the mother, while the male aphids can sexually reproduce with the females. Yes, their sisters.

Reproduction without a male is called parthenogenesis and is relatively common in insects, amphibians, and reptiles.

“Geckos, whiptail lizards, some snakes, and even Komodo dragons can reproduce asexually if the conditions all for it,” Noor said. “Essentially, though, they’re just making clones of themselves, if that’s the case.”

In biology, the Gorn would be an r-selected species. That means they can reproduce faster and out-compete any other species in their environment that are looking to use the same resources. In r-selected species, many offspring are produced, but not all of them will survive.

It may become clearer if we can pull back and look at it from a distance. Gorn eggs are laid inside hosts, say 20 colonists, each getting four viable hatchlings inside them. 80 hatchlings show up. That’s explosive growth and more than the environment can support, so through competition for resources (via siblicide), their number drops until more hosts are found.

This style of explosive growth might be ringing recognition bells in your head – it’s quite similar to the exponential growth seen in viruses. Put a Gorn hatching in a large city, and let it spray. Each host produces four viable offspring, which then spray others, generation after generation. That was COVID-19. Virus spread can be measured by its Basic Reproduction number, R0 (R-naught). During the height of the pandemic, epidemiologists were hoping for the R0 to drop below 1, meaning that every infected person infected, on average, less than one other person, making it extremely difficult for the virus to spread. During the initial COVID-19 outbreak, we looked at the classic Batman: Contagion storyline for examples of the R0 of the “Clench” virus and its exponential growth.

Treating Gorn like this, each infected person could infect four more people, so the R0 for Gorn would be 4. Not wildly big, but large enough to do the job. Of course, the hatchlings would also be going after one another, so the analogy’s not perfect.

But if you want to think of the Gorn as intelligent, viral space dinosaurs, that does get the idea across.

With all that in their favor, what stops the Gorn from taking over star systems and, ultimately, galaxies?

I’m going to go with the Federation. And probable Klingons and Romulans, too. Maybe the Borg. Competitors for resources on a galactic scale.

That Gorn Reproduction Thing…

If you were thinking that Gorn can’t just asexually reproduce and make clones on top of clones on top of clones, you’re right. No species can do that. There’s no genetic variation within a population of clones. Populations with little genetic variation suffer from the Founder Effect, which is not good in the long run. Genetic variation allows for adaptation to the environment, as well as protection from threats. If everyone’s genes are the same and a disease is introduced, no one has a defense for it, and the population is wiped out.

Diversity is good. Lots of genetic variation beats little genetic variation every time.

So a single hatchling could establish a small colony of Gorn on a breeder world, but then what? Yes, there would be some mutation when the DNA of the Gorn is being copied, but that wouldn’t be a huge amount. Asexual reproduction will only get them so far. You need sex to really shine as a species.

Come out on top of the heap on a Gorn breeder world, and you may get picked up and taken back home.

To have sex.

Sexual reproduction allows for a transfer and recombination of genetic material, making the offspring, at the very least, different, but more likely, more robust. More robust offspring can better handle environmental challenges. Without sexual reproduction, your species is at a serious disadvantage to those that do.

That Gorn Evolution Thing…

How would you end up with a Gorn world, anyway? In the world of Star Trek, it’s a given – lots of alien species. But let’s play in our sandbox — Earth.

Biologist Stephen Jay Gould famously explained the chance nature of evolution by saying that if you “wound the tape back” on earth’s evolution, there’s no guarantee you would end up with humans being the dominant species.

Biologist Jonathan Losos, author of Improbable Destinies: Fate, Chance, and the Future of Evolution, explained Gould’s classic line through the use of Disney’s The Good Dinosaur. The Chicxulub Impactor (the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago) missed the Earth in the film. As a result, dinosaurs remained the dominant life forms on the planet but continued to evolve.

On that earth, our Gorn analogs, theropods like Velociraptors and Troodons, were doing well — feathered, hunting in packs, and more than likely, demonstrating other bird-like behaviors. Given their anatomy (theropods are “lizard-hipped”), these bird-like dinosaurs would likely maintain the classic “velociraptor” style, their heads canted forward, even though they walk on two legs. As their heads get bigger over millions of years (to hold bigger brains), their tails would have gotten meatier to counterbalance.

This isn’t to say that a fully bipedal humanoid (or Gorn)-style dinosaur couldn’t have evolved on earth — it’s just that the theropods were doing pretty well, and the pathway for the evolution of a proto-Gorn wouldn’t have been a clear one. They would have had tough competition from the already-established theropods, which certainly would’ve seen them as a delicacy.

Back to Losos’ theropod-ruled earth…

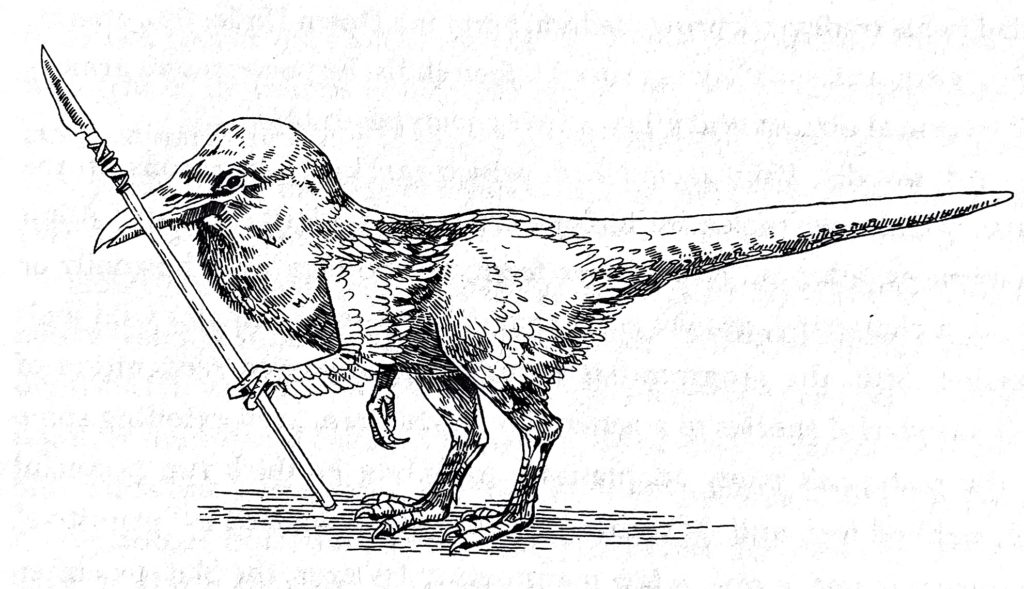

As Losos explains, there’s no reason to think that these super-smart birds wouldn’t have adopted the use of tools, artificial colorations, tribal society, and even technology. As the illustration from Losos’ book offers:

Losos’ take on a theropod on an earth that dodges the asteroid a few million years on (Image, Jonathan Losos)

But as for “pure” Gorn on another world? Noor: “I don’t think it’s a stretch. All of these features that we see with the Gorn are at least very close to features we see in the animal kingdom on earth, and evolution does like its tried-and-true patterns for overcoming environmental obstacles. So it’s not a stretch to think that all of those characteristics we’ve been talking about could have come together in one particular, large reptile. Nothing there is breaking the laws of physics or something like that. I’m just glad it didn’t happen on Earth.”

Like all Strange New Worlds fans, Noor wants to see more Gorn, and hey, if there’s an opening for a science team to set up a research outpost on the Gorn homeworld someday (safety must be guaranteed), sign him up. “I really want to know their origin,” Noor said. “I’m wondering if the Gorn are going to touch on what we saw in the Voyager episode, ‘Distant Origin,’ where some dinosaurs from Earth somehow moved into space and would up in the Delta Quadrant, and evolved their civilization, or if they’re something entirely new. I hope we get to find out.”